Sentry Page Protection

Please Wait...

Reginald Melville Ward Lowe

Burma Railways Engineer

1928-1942 and 1945-1947

"Some Memories of Burma and the Burma Railways"

press ctrl f to search this page

Reginald Melville Ward Lowe, as T/Captain, Indian Army Engineers, Dec. 1942

Reginald "Reg" writes in the preface to these memoirs - " Two years ago (c. 1991) I wrote some memories of our life in Burma during the years 1928 -1942 and 1945-1947, the intervening years being spent in military service in India, to which country we evacuated when the Japanese invaded and occupied Burma... (After a car accident in 1993 his dining room was temporarily converted to a bed room and his original manuscript was "lost" in this re-shuffle.) Having spent some considerable time (and some money) in producing these "Burma Memories" I was saddened by their loss. Fortunately, my nephew's charming wife had previously made a photocopy for herself and so was able to give me copies and so I was back to square one, as it were, except for the loss of some original photos and documents.

|

At the age of 87, I propose to record here some of my recollections of working as a Civil Engineer from 1928 to 1947 on the Burma Railways:-

After obtaining the necessary technical qualifications, in my case B Sc. (Eng.) London, A.C.G.I. (Associate of the City and Guilds Institute of Engineers) and D.I.C. (Post Graduate Diploma of the Imperial College of Science and Technology in Structural Engineering) and working on some engineering projects in London in 1926 and 1927, I was informed that the Burma Railways Company, whose company head office was in the City of London, required some young Civil Engineers. Knowing nothing of Burma, but tempted perhaps by the offer of a sterling salary more than my wage at that time, I attended an interview with the Company Directors at their London office. I was appointed by them in late 1927 and made my way to Burma, arriving by ship at Rangoon, at the beginning of 1928. Norman McAllister, then Assistant Engineer in Rangoon, met me and took me to the Head Offices where I was introduced to various senior officers of the Railway staff, including the Chief Engineer G.A. Hicks, the Deputy Chief J. Rowland (later Sir John Rowland) the Agent Mr. Glascott, Mr Crosthwaite (later Sir Bertram Crosthwaite) and Mr Darby of the Traffic Managerial Staff. After spending a few days in Rangoon getting to know other members of the Head Office Staff and also purchasing some furniture, kitchen equipment and crockery, I then had to engage a personal servant who could cook, apart from looking after my new possessions. he also had to be able to understand English and Burmese. I obtained an Indian servant who had been born and bred in Burma and I found him to be reliable and trustworthy. Meanwhile, I wondered as to which part of the Railway system I was likely to be posted. Perhaps I should explain here what constituted the Burma Metre Gauge Railway, whose total main line track mileage was, I think, about 1800 miles..... This track mileage does not include the double track lines (e.g. Rangoon to Mandalay) consisted of: (1) Rangoon to Mandalay via Pegu, Toungoo, Pyinmana, Yamethin, Thazi and Myitnge. (2) Mandalay to Myitkyina via Ava, Sagaing, Ywataung, Shwebo, Kanbalu, Wuntho, Naba, Mohnyin and Mogaung. (3) Pegu to Martaban via Mokpalin and Thaton. (4) Moulmein to Ye via Thanbyuzat... (5) Thazi to Shwenyang (the branch line up into the hills to 3,800 feet in the S. Shan States.) (6) Mandalay to Lashio (the branch line up into the N. Shan States via Maymyo at about 3,500 feet altitude and the summer residence of the Government of Burma and also the uncompleted rail link to the Chinese border. (7) Rangoon to Prome, Tharrawaddy and Bassein via Insein (the site of our Loco. Workshops and the offices of the heads of the Locomotive and Electrical Departments of the Railway. (8) Thazi to Myingyan via Meiktila. (9) Myingyan to Mandalay. (10) Pyinmana to Kyaukpadaung via Taungdwingi (this line approached the Burma Oilfields.) (11) Ywataung to Ye-U via Monywa on the Chindwin River. Most of the branch lines were from 90 to 140 miles in length. There were also some shorter lengths of track in Rangoon and, I think, also to the Oil Refineries at Syriam. In addition to the track mileage on which passengers and goods trains ran daily, there was also the rail tracks in all Station Yards and other sidings which amounted to many hundreds of miles in total length. I mention this fact as the maintenance of all tracks, bridges and buildings was the responsibility of the Engineering Department. Until the Ava Bridge over the Irrawaddy from Ava to Sagaing was built and opened to rail and road traffic in 1934, the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company's river steamers operated the railway ferry services over the Irrawaddy river at Mandalay and Letpadan and also over the Salween river from Martaban to Moulmein. My first posting was as Assistant Engineer in charge of the railway track from Wuntho to Myitkyina with my headquarters at Katha on the Irrawaddy river and at this end of the 12 mile branch line over the hills from Naba Junction. This line was the northern half of the Sagaing to Myitkyina District with my district Engineer's headquarters at Ywataung. When receiving my orders to this posting to the furthermost section of the railway from Rangoon, I was also made aware of its reputation as a malarial part of the country and was advised to take the necessary precautions and equip myself with mosquito nets etc. On my arrival in this district, I had to meet my District Engineer Mr A.G. Vanderbeek, who resided in Ywataung. Other railway Officers also there included the District Traffic Superintendent Mr Brewitt, the District Loco. Officer Mr Lewis, and the Assistant Engineer Mr Cambridge. I then proceeded to Katha to take over my section of the Railway from the Assistant Engineer there Mr G. Stuart, who was due to go on leave. |

Top row: Hailes (T), Bodeker (L), Claudius (EE), Ferguson (L), Kendall (E), Hayes (E), Vanderbeek (E)

3rd Row: Parker (A) Blanchard (L), Stewart (L), Johnson (L), Dr. Carrier (M), (4 Burmese Officers, unfortunately names forgotten,)

Rose (S), Binnie (L), Glanville (?)

2nd Row: - ? - , Milne (T), Telfer (SN), - ? - , Dunn (L), Gainsford (L), Fane (T), Air (E), Cotton (S), Lowe (E), Brewitt (T).

Front Row: Long (S), Bevan (E), Richie (E), Mackie (L), Rowland (E), Crosthwaite (T), Darby (T), Chance (A), Dr. Taylor (M), Pratt (L), Aikman (T).

3rd Row: Parker (A) Blanchard (L), Stewart (L), Johnson (L), Dr. Carrier (M), (4 Burmese Officers, unfortunately names forgotten,)

Rose (S), Binnie (L), Glanville (?)

2nd Row: - ? - , Milne (T), Telfer (SN), - ? - , Dunn (L), Gainsford (L), Fane (T), Air (E), Cotton (S), Lowe (E), Brewitt (T).

Front Row: Long (S), Bevan (E), Richie (E), Mackie (L), Rowland (E), Crosthwaite (T), Darby (T), Chance (A), Dr. Taylor (M), Pratt (L), Aikman (T).

E = Engineering, T = Traffic, L = Locomotive, A = Accounts, M = Medical, EE = Electrical, S = Stores, SN = Signals, TL = Telegraph

Other Officers of the railways not in the above photo, as they were out in the districts or on leave at the time:-

Engineering Dept.

Toller, Procter, Butcher, Hossack, Hawtrey, Gawthorne, Cambridge,

Markwick, McAllister, Cant, Strictland, Stuart, Jeffree, Edwards, Manifold,

McCabe, Smith, Stone, U Kyi Win, U Shwe Shane.

Traffic Dept.

Fitzherbert, Loveland, Blakeney?, Lee, Coward, U Sett Kaing.

Loco. Dept.

N. Johnson, Cardew, Lewis, Palmer, Hadfield, Powell, A. (or R.) Johnson.

Telegraph Dept.

Downing, Howard.

My apologies to those whose names I have forgotten or omitted.

Engineering Dept.

Toller, Procter, Butcher, Hossack, Hawtrey, Gawthorne, Cambridge,

Markwick, McAllister, Cant, Strictland, Stuart, Jeffree, Edwards, Manifold,

McCabe, Smith, Stone, U Kyi Win, U Shwe Shane.

Traffic Dept.

Fitzherbert, Loveland, Blakeney?, Lee, Coward, U Sett Kaing.

Loco. Dept.

N. Johnson, Cardew, Lewis, Palmer, Hadfield, Powell, A. (or R.) Johnson.

Telegraph Dept.

Downing, Howard.

My apologies to those whose names I have forgotten or omitted.

|

On the whole, I think I can say that I enjoyed my three years stay and work in this part of Burma, which is well provided with flora and fauna. Many lengths of the railway ran among hills and forests and, as I was the possessor of a B.S.A. double barrel 12 bore shotgun and a Colt 44 bore rifle and was keen on shooting, I was able to relax from my railway work at times by shooting either jungle fowl or Pheasant or Partridge and, in season, Snipe and Woodcock.

There was also one occasion when I was involved in a hunt for a wild animal, a Panther, which had attacked and killed a Burman's pet dog as he was walking near a patch of jungle. I was "on line" that day (i.e. on tour) and was in my inspection railway carriage which was "parked" in a siding at Naba Junction. I was busy with some office work and was about to have my lunch when a very scared Burman arrived and told my servants what had happened. He then went on and told his story to the Station Staff and, shortly afterward, I saw the Station Master, a Burman whose name I can't remember and was known to be a keen hunter, with his gun following the man into the nearby jungle. About twenty minutes or so later, while having my lunch, I heard the distant sound of gunshot and thought that the Station Master must have found and shot the animal. Anxious to see what had happened, I grabbed my 12 bore gun and some cartridges and went in the direction of the gunfire. I hadn't gone very far when I met the Burman, who now had scratches on his body, was bleeding and coming to call me. A little further on in the jungle, I met the Station Master, who told me that when he arrived at the place where the man said his dog had been taken by this animal, the jungle was so thick that they could see no animal. His Burman guide, however, keen to prove his story about the wild animal taking his dog, then tried to force his way into this patch of jungle and the next minute the man was attacked by the wild animal and the gunshot I had heard was a shot fired by the Station Master to scare the animal off the man. He could not shoot at the animal for fear of also shooting the man. By now, other men from a nearby village joined us and, knowing that this dangerous animal was still in this part of the jungle, they decided that, with their dahs (swords) which they always carried and sticks cut from the trees, they would approach this jungle from some open ground on the far side and "beat" the animal towards us so that we could shoot it. The Station Master and I, with guns loaded, took up position standing about fifty feet apart to the right and left of the patch of jungle and the villagers started "beating" with much shouting and beating of bushes. The panther objected to this, as presumably it was still eating its kill and roared and charged at the beaters who hastily retreated. However, as more beaters arrived, they soon resumed the "beat" and I saw the animal run out of its patch of jungle and come up a path towards me. As I waited for it to come within range of my shotgun, the Station Master, who was further away from it and hadn't as good a sighting of it, fired. I could see his shot miss the panther and the animal stopped and leapt into the bushes on the other side of the path and dsappeared. I was very diasppointed that we hadn't shot it. Some two weeks later, I heard that it was still scaring the local villagers and killing their cattle and that some Shikari had "sat up" near a kill and had "bagged it." I must apologise for this long diversion from my job as an Engineer on the Burma Railways. At the age of 25 at this time, I kept reasonably fit and enjoyed my work and also the social life in headquarters in Katha, where, in the evening, in the local club, one would meet some of the other officials, such as the Deputy Commissioner, the Police Superintendent, the Forest Officers and their wives and the young bachelor members of the timber firms such as Steel Brothers and the Bombay Burma Trading Company. I must have arrived in Katha shortly after Eric Blair, better known as the writer George Orwell, who had been the Assistant Police Superintendent there, had left. His novel "Burmese Days" reminds me of life there in those times. |

|

One usually played tennis on the club courts in the evening and later relaxed with a drink and a game of bridge or billiards in the clubhouse. One was also able to relax and enjoy some of the social life when on tour at the northern end of the railway at the town of Myitkyina.

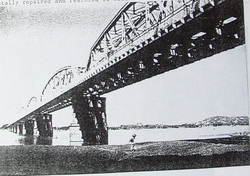

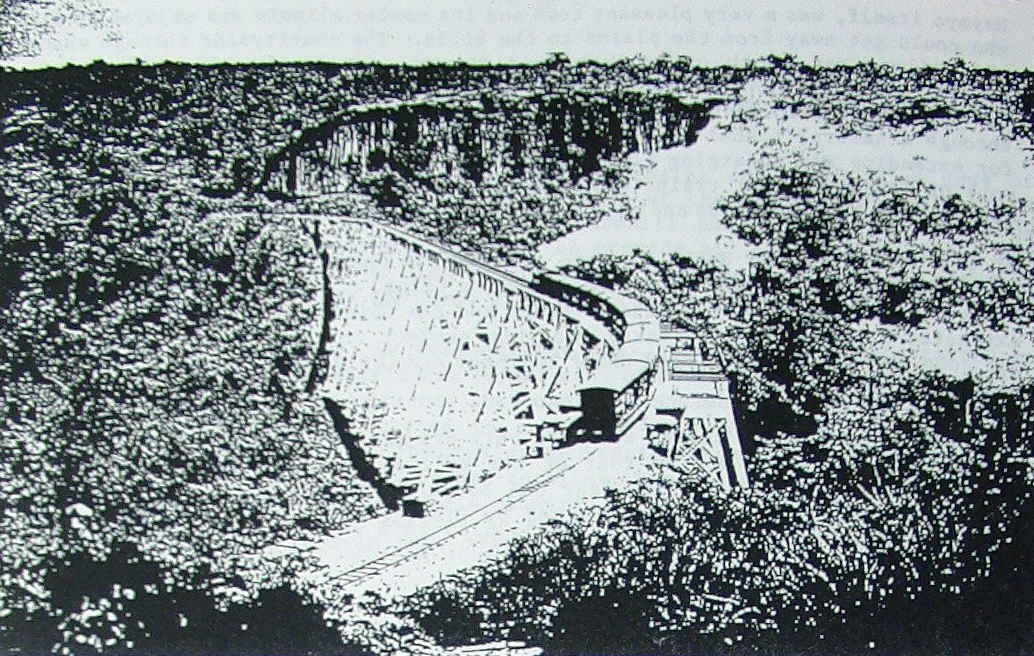

Although very much on my own, and some 600 miles from Rangoon and 200 miles from my District Engineer's headquarters, I was at times required to proceed south to help in restoring rail communications when heavy floods during the rainy season washed away parts of the railway line and bridges. I recall one such occasion when, being the only railway officer on a train travelling to Shwebo, the flood waters from the range of hills to the east of the railway and flowing towards the west, had been held by the railway embankment and restricted by the only railway bridge there of three 20 foot spans through which the flood water was rushing. The driver of the train, alarmed by what he saw, stopped the train just short of the bridge and came to ask me whether or not he should take the train over the bridge. It seemed to me that there was as much danger in waiting to decide this as delay could make the bridge more unsafe and there was also the possibility that the build-up of the flood water could breach the embankment on which the train was standing. So we had to take the risk of taking the train over the bridge which was successfully accomplished but only just in time, as the bridge was washed away shortly after and had to be rebuilt. In another part of this section of the railway, where between the stations of Padu and Ketka the track ran for some 3 or 4 miles across some rather low-lying country, the flood had formed a large lake with only the tops of the trees visible and the railway track for at least a couple of miles was under water by about 12 to 18 inches. It had to be decided, as there was no sign of the water level subsiding, to raise the track level by inserting stone boulders and ballast under the track and at the same time digging with manual labour a channel a few miles long from the lake to the nearest river bed to reduce the water level. Needless to say, even with a large labour force recruited from the neighbouring villages, it was a few weeks before the normal running of the trains could be resumed. In 1931 I had my transfer orders. I had, during my three years in this northern most section of the railway, managed to avoid getting Malaria, for which the area was notes. Instead, through unknowingly eating contaminated food in a railway "refreshments room," I contacted Amoebic Dysentery. The only treatment for this appeared to be injections of Emetine Hydrochloride. This stopped the effects of the Dysentery so that one could continue one's normal activities but did not cure it. Although I should have taken some casual leave and gone to Rangoon for proper treatment, I continued working and at intervals of two to three months, receiving an Emetine injection. I paid for my stupidity regarding this a few years later when, owing to Amoebic cysts having got into my blood, I found all my joints seizing up and I could walk only with some difficulty and with the help of two walking sticks, but more about that condition later.Head Jack Jeffree came to take over from me at Katha and I moved to kalaw, at about 3700 feet up in the S. Shan States. My new section of the railway extended for about 160 miles from Myingyan to Shwenyaung at the north end of Inle Lake and not far from Taunggyi which was only approached by road and was the headquarters of the Civil District Commissioner of that area. It was pleasant to be living and working for a while in the cooler climate of the hills. Owing to the gradients of up to 1 in 25 and the sharp curves (up to 17%) of the railway track necessary to negotiate the hills and climb to an altitude of nearly 4,000 feet, all trains between Thazi and Shweyaung, a distance of about 90 miles, were hauled by Beyer-Garrett Locomotives. These heavy articulated locomotives, with their larger boilers and two swivelling power bogies were capable of hauling quite heavy loads up the hills but one of the worries of the Engineer responsible for track maintenance was the wear caused to the rails, especially on the sharp curves. There was also some wear caused by the sorbitic steel rails to the tyres of the engine wheels but this was the responsibility of the Locomotive Department. Lubrication of the inner sides of the outer rails on sharp curves was considered as helping to reduce wear, but the climate conditions and the possibility of the lubricant spreading over the rail heads and thus reducing friction and so the tractive force of the locomotive did not recommend it. During the monsoon season of, I think, 1931, the continuous rain over some days, caused a landslide of part of the hillside at an altitude of about 3,800 feet and the rocks, earth and trees had fallen into the railway cutting and completely blocked it. The driver of a train coming up the hill saw this blockage in time to stop his train just short of it. The news of this landslide soon reached all stations and all trains stopped at the nearest stations. The site could only be reached by rail so I reached it as soon as I could by railway trolley. Having seen the hundreds of tons of earth and boulders to be moved only by manual labour, no mechanical means available or workable on the steep hillside. I reported the position to my District Engineer at Yamethin and to Rangoon and arranged for a large labour force, with the necessary tools and explosives for blasting and breaking up the very large boulders in the blockage. Working day and night using lights from portable generators and with a large labour force of some 200 men drilling, blasting, digging and man-handling the debris out of the cutting and throwing it down the hillside it took us the best part of a week to clear the line. The urgency for this work was not only the need to restore the railway for passenger travel but also for the export of fruit, mostly oranges from the Shan States. Of course, whilst this work was progressing, we were also having to contend with the rain which continued and caused further falls of earth and stone. One night as I was in the "cutting" with the men working there and was holding an umbrella over me as it was raining, a large stone fell from the hillside above and went through my umbrella, just missing me. I quickly folded up the umbrella and pretended that nothing had happened. Sometime in 1932, I was transferred from Kalaw to the Ava Bridge Construction with headquarters at Ywataung, the other side of the Irrawaddy from Mandalay. The river at the site of the bridge is nearly three quarters of a mile wide and the bridge spans it with nine spans of 360' steel trusses; one span of 260' steel truss and 6 approach spans of 60' girders, all carrying the centre rail track and a roadway cantilevered out on each side. When I arrived the abutments and all piers had been built and the erection of the steel work had started from the west end of the bridge, the third 360' span over the river being nearly completed. The steel spans of the bridge had to be constructed at a height above the highest flood water level of the river to clear the superstructure and funnels of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company's steamers, which meant a height of about 30' as far as I can remember. My work included supervision of the bridge approaches and rail track and the building of a station halt at Sagaing. The Ava Bridge which now made direct road and rail communications possible between south and north Burma, was opened to traffic in 1934. The railway Engineer in charge of the bridge construction was Mr G.G.T. Toller and Mr Cyril Kendall was one of the Assistant Engineers throughout the construction work. My next posting for a few months was to Myitnge (near Mandalay) where the Railway Carriage and Wagon Workshops were situated. My section of railway track extended from Myingyan to Mandalay and thirty miles north of Mandalay to Madaya. The District Engineer at Mandalay was Bert Hayes, who kindly lent me his compressor and paint spraying outfit, which enabled me to respray my Chevrolet car. Our social life, when not on tour, was often spent at the Mandalay Club, which was situated within Mandalay Fort, where also was the old Mandalay Palace. These were all destroyed in the course of the fierce fighting to capture the Fort from the Japanese in 1944. From Myitnge late in 1933, I was transferred to Moulmein, Mr McCabe, just back from his home leave, taking over my job there. I remember my stay in Moulmein as Engineer in charge of the Moulmein to Ye branch of the railway. The only other railway officer there at that time, was the Assistant Traffic Superintendent Mr Fitzherbert, whose house was next to mine. Moulmein, itself, was quite a pleasant town on the east side of the Gulf of Martaban and so separated from the rest of Burma by the wide mouth of the Salween river. While at Moulmein, I managed to persuade my District Engineer in Rangoon to let me have a motor railway trolley, which he kindly did, provided that I could get it and the railway wagon which housed it (weighing about 4 tons) over the two miles or so of river between the railway terminal at Martaban and Moulmein! By laying an extension of rail track down to the river bank at Martaban and connecting it to a floating jetty, I managed to get the wagon loaded onto a boat and across the water to a jetty at Moulmein and, therefore, was able to do my track and bridge inspection work much quicker using the motor trolley. A few miles from Moulmein by road there was a swimming pool and a landscaped garden with a pavilion with facilities for showers and changing rooms. A private property which we were allowed to use and did at weekends with our friends. Picnics there, especially on moonlit nights were very popular. We also sometimes went by road to Amherst, a small seaside resort about 40 miles south of Moulmein, where it was pleasant to swim and picnic on the sandy shore. One had to swim strongly at times to resist the strong currents which tended to sweep one away into the bay. After a stay of about 18 months or so in Moulmein, I was transferred to Rangoon (in 1934/5) with responsibility for the Pegu to Martaban section of the railway. This 150 miles of track includes the Sittang Bridge which crossed the Sittang river restricted in width to 800 yards just west of Mokpalin with, as far as I can remember, 11 spans of 200' steel trusses. The river is very fast flowing under the bridge and tends to scour the foundations of its piers which need the protection of large quantities of stone boulders placed around them at not infrequent intervals. The Engineer is required to take regular inspections of this bridge. In Rangoon, I shared a house with Mr Aikman and Mr Glanville of the Railway Traffic Department and enjoyed the social life there when not out on tour. As a young bachelor in Rangoon one frequented the "Silver Grill" where one wined and dined and was entertained with music and cabaret shows and as a member of the Rangoon Gymkhana Club, with its large club house and tennis and squash courts one played tennis, squash or billiards and met the young ladies at the Saturday evening dances there. In October 1935, I was granted my 9 months home leave, which was long overdue. After handing over to my successor, I sailed from Rangoon in November. During my holiday and on Good Friday 1936, when visiting family friends of longstanding who lived near Folkestone, I met their daughter, Marjory, an attractive young lady and a qualified chemist who was working in Dover. We had met before in the 1920's when I was a college student and she was still at school. Needless to say, we fell in love and were married on her birthday in July 1936 and she accompanied me on our voyage to Burma in August that year. Back in Rangoon, we stayed for a short while in the comfortable Railway Officer's rest rooms at Rangoon station, where my old servant came to greet me and see what the new "Memsahib" was like. He seemed to approve and we acquired another servant by the name of Raj who had been a lady's servant and was experienced in laundering, ironing and generally looking after ladies clothes. He also understood and spoke some English. My next posting was as Assistant Engineer at Pyinmana, a station on the main line about half way between Rangoon and Mandalay. My section of railway track and bridges extended from Pyinmana northwards to Thazi junction on the main line and westwards on the branch line from Pyinmana to Kyaukpadaung by the Irrawaddy river and close to the Burma Oil Company's oil fields, a total distance of about 160 miles. I took over my duties at Pyinmana from Cyril Kendall and we moved into the house which was pleasantly situated on a hill overlooking a lake. |

Pyinmana Club

|

We soon got to know the other official residents in Pyinmana by joining the club where, in the evenings, one played tennis and later, in the clubhouse, bridge or billiards or sat and talked or read the English papers. The membership included the Sessions Judge, Mr Healy, the Director of Agriculture, Mr McLean, the District Forest Officers, Mr Burgess, Mr McKay and Mr Warwick, the Agents of the firms such as Steel Bros. and the sub-divisional officer Mr Glass, I.C.S. Most of these officers also had their wives with them so we enjoyed many social activities together, especially when the younger bachelor members of the timber firms came in from the teak forests where they had been working.

My wife's parents, obviously anxious to see the far away country their daughter had gone to, sailed for Burma by a Bibby Line steamer and arrived in Rangoon in December 1937, where we met them, the railway powers-that-be, having kindly allowed us the use of a comfortable saloon inspection carriage attached to the main train, we journeyed the 200 miles to Pyinmana, arriving at our house at night, where our servants greeted us and had all electric lights on and some refreshments. Our elderly relations spent two months with us which included the Christmas holiday, where they witnessed the Eastern custom of one's railway contractors coming on Christmas Day to garland us with Marigold flowers and presenting us with sweets and fruit and sometimes also a bottle or two of wine or spirits. My rejection of any such presents from those contractors whose works I had found unsatisfactory, was considered by my mother-in-law to be ungracious until I explained the reasons to her. Our local friends were most helpful in entertaining our in-laws and showed them various interesting local activities such as elephants at work dragging the large teak logs which had been floated down the river and had got stranded on some obstruction and required to be re-floated so that the next flood would take them further down the river. They left Burma in February 1937 and sailed for home. My wife, a qualified chemist, was asked to assist the other ladies in the town, which included some Burmese and Indian ladies, in helping to "run" a new child welfare clinic, which she was pleased to do. My railway work meanwhile, was somewhat routine maintenance work which necessitated my being on tour on my 160 miles of railway for at least 15 days a month. Usually not more than three days at a time on tour and then a return to headquarters to attend to office work. Our servants were used to the usual procedure for touring for which we had a private railway saloon carriage allotted to us and which, on my request to the Railway Station staff, would be attached to the end of the particular train I wished to travel by and detached at a particular station and shunted into a siding. The accommodation in the inspection carriage consisted of a saloon with two berths, a table and 2 chairs, various cupboards for crockery, glassware etc. and shelves for books and papers. Adjoining the saloon was the bathroom and toilet and a passageway with sliding doors led to the kitchen beyond the bathroom which also, apart from the charcoal cooking range, had berths for the two servants, and the cook who usually toured with me and cooked and served the meals. My wife usually accompanied me on tour and sometimes we met other railway officials on tour with their wives and could spend a pleasant evening together having drinks and exchanging news. Once a month I had to accompany in my inspection carriage the "Pay Special" which had the money and the pay clerks from the Rangoon Head Office on board and stopped at each station to pay the staff. I had to witness all payments to the Engineering staff and sign the pay sheets. This special train also had wagons containing the foodstuffs and cooking oils and other household necessities which were not easily available in the remote areas in which some of the staff lived and these things would be sold to them from the train. In case of attack by dacoits (robbers) this train had to be accompanied also by armed Railway Police. |

Railway Officers Inspection Carriage

|

While in Pyinmana, our friends Mr and Mrs Baillee of the Bombay Burma Trading Co. invited us to join them for the 1938 Christmas Camp in the jungle, which, needless to say, we were keen to do. All the necessary tents and camp equipment, together with our personal baggage, food and cooking pots were carried the twelve miles or so from the railway station at Lewe into the forest on the backs of six of their working elephants and we followed on foot. The elephants, of course, moved faster than us, so that by the time we reached the camp site in a clearing in the teak forest, our tents had been pitched by the servants with our camp beds, tables and chairs in place. In the centre of our camp site, the villagers from a nearby Burmese village had also erected a shelter from the branches and leaves of the jungle trees and this was used as our "lounge" and "dining room." Also, suitably positioned among the adjoining bushes were our temporary "washing room" and "toilets!"

We slept well in our tents and were not aware of many jungle sounds at night, as the wild animals prowled around. I presume our camp fire, which our servants kept alight while they sat and talked or slept, was a deterrent to any straying animal, but I well remember the crowing of the jungle cocks at dawn and the occasional screech of a distant peacock. The elephants which carried our tents and baggage to this camp site, had gone on with their mahouts to do their usual work of extracting the teak logs in another forest nearby. We spent three days in the "Christmas Camp" during which we also visited other friends from Pyinmana, the Warwicks, who were also spending the Christmas holidays in another jungle camp. Jay Warwick was a District Forest Officer and head of the Forest Department College in Pyinmana. Towards the western end of my section of the railway and not far from Burma's oil fields, there rises out of the comparatively flat landscape, the 3,500 ft. high Mount Popa, a long-extinct volcano. It is reported to be the home of the dreaded Hamadryad snakes or King Cobras, a venomous snake up to 10 or 12 ft. in length and up to 8 or 9 inches in girth. The Burmese inhabitants of the village on the mountain are alleged to live in a more or less friendly relationship with these snakes. With our friends, Mr and Mrs Edwards of the Railway Engineering Department, we decided one day when on tour together, to visit this village and see for ourselves. So having arranged some horse drawn transport for the 20 mile journey, we arrived there at midday and found a rest house on the edge of the village, where we were able to rest and enjoy the picnic lunch we had taken with us. After a short while, some Burmese men and women appeared from the village carrying two large baskets, from which they produced two large Hamadryads and let them loose on the ground in front of us. With their heads raised and hoods extended about 2 feet above the ground, they were certainly "handsome" snakes and a Burmese woman danced in front of the snakes and concluded her dance by kissing the snakes head. Obviously, they had removed its poison fangs or it would have been a kiss of death! However, we paid them for the "entertainment" and made our way back down the mountain after taking some photographs. One of the Railway Engineers responsibilities is the water supply at the stations where it is necessary for the engine tenders to be filled, apart from water for domestic use. In most cases, water is obtained from a nearby well from which it is pumped to overhead storage tanks and piped from there to the water columns and other distribution points. It was found necessary to increase the water supply at one of the main line stations on my section of the railway line at Thazi junction and in order to find an underground source of water which could be tapped, a professional dowser was engaged. I had heard of the science of dowsing, where a forked twig held by the dowser as he walked over the ground, dips towards the ground when he is over the spot where there is water underground, but I had never seen it done. I met the dowser, an Englishman, who had recently come out from England, presumably at the request of the Government for this work, and took him to the location where we wanted to find a source of water supply. He walked over the ground with his forked twig in front of him and I saw it suddenly bend down and then straighten up again as he walked on. It did this again as he walked on a parallel path a few feet away. He suspected that this behaviour of his twig might indicate the presence of an underground water main, so he walked again a few yards further to the left and, with his twig still bending down as he passed over the same line, we realised that there was an underground water pipe there. So we let him choose another site for his dowsing, which he did and his forked twig soon behaved in a similar manner. I was fascinated at seeing this strange phenomenon and asked him if I could try to prevent his twig from bending as he held it firmly over the spot where there was underground water. He agreed and as I held the front end of the twig to prevent it bending down, it broke in his hands and I saw that the palms of his hands had been marked by the vigorous twisting of the twig. I then asked him if the particular twig he had been using had any special properties and he said no, and, as there were many bushes near us, we soon cut some suitable Y shaped twigs from them, which, in his hands behaved in this strange manner, but not in my hands as he suggested I tried to see if I could be a dowser. Later a tube well was sunk at the site he indicated and a supply of water was found. Shortly after Britain declared war on Nazi Germany and the Second World War against the so-called Axis Powers started, we were transferred from Pyinmana to Rangoon in October 1939, an event, needless to say, quite unconnected with events in Europe. We were, however, much concerned as to how our folks at home would fare when the bombing started, as my parents were living near Croydon and my wife's parents were near Folkestone. As it happened, later during the war when Germany resorted to sending V rockets and flying bombs over the south east of England and London, their houses were so badly damaged by these falling very close by, that while they luckily avoided being killed, they had to move to other houses. The Engineer who succeeded me in October 1939 at Pyinmana was John Hawtrey, I in turn, took over the job of Assistant Engineer, from George Cambridge. Our house in Rangoon was No. 36 Prome Road, about a mile and a half by car to my office in the Railway Headquarters Building near Rangoon Railway Station. |

|

The work of the Assistant Engineer in Rangoon not only involved the maintenance of all main and suburban line tracks and many siding in goods yards and the engine workshops at Insein, but he was also responsible for the repairs and maintenance of all service and residential railway houses in Rangoon and Insein, which were many. This latter work sometimes required the exercise of some diplomacy on the part of the Engineer, when the requests by the wives of some senior staff for some special work to be done as soon as possible to their houses, conflicted with other work. However, there were some compensations in living and working in the Capital as one was able to enjoy a social life as a member of the Kokine Swimming Club, the Pegu Club and the Gymkhana Club and there were also good shops, restaurants and cinemas.

Despite being fully occupied with our work and social activities, we looked anxiously for news from home of how the war was affecting them. Fortunately not much at that time for apart from the British Expeditionary Force going to France and helping to improve the French made defences along the Franco-Belgian border, there was no actual large scale fighting there. Germany was busy invading Poland and its Italian partner, Mussolini, attacked Albania and Abysinia. German U boats were active at sea, attacking merchant ships and we heard of magnetic mines laid in the seas around British coasts. Britain lost some one and a half million tons of merchant shipping in the first six months of this war, but Germany also lost some submarines. We were much cheered when we heard of the battle of the River Plate when the British Cruisers "Ajax", "Achilles" and" Exeter" put the German pocket battleship "Graf Spee" out of action and caused her to be scuttled. There was much propaganda and we heard of a Dr. Goebbels and "Lord Haw Haw" and of "Quisling" and of the German Foreign Minister Dr. Ribbentrop and, of course, the rantings of Hitler. We were still in Rangoon throughout 1940 and depressed at the news of the German blitz on Belgium, Holland and France which, during May 1940, resulted in the retreat of our forces, their return from the beaches of Dunkirk, the collapse of French resistance and the surrender of France to Nazi Germany. The Battle of Britain was fought in the skies over Britain as Hitler and Goering tried to destroy our air defences and force Britain also to surrender when they invaded this Island! Japan at this time was still engaged in war in China, which, with the building up of her German trained armed forces, was also a good experience for them. We did not know or suspect that she was planning for future greater conquests and that Burma and Malaya were in those plans! Japan's invasion of China did not concern us much in Burma in 1940 nor the military occupation of Indo-China in 1941 but her continued pressure on China and the blocking of China's ports by Japan's greatly increased navy necessitated in China having to find other means of getting supplies into that country and so Chiang Kai Shek appealed to Britain to allow these supplies to enter China through its "back door" i.e. through Burma via the railway to Lashio. It was about this time, i.e. April 1941, that I was transferred from Rangoon and posted to Maymyo as Engineer in charge of the Mandalay to Lashio branch line with the special responsibility of surveying and reporting on the possibility of increasing the capacity of this single track line. This railway track which, after reaching the N. Shan Hills about 15 miles east of Mandalay, climbs for 12 miles continuously up in a 1 in 25 gradient to an altitude of 3,500' where it reaches the hill station and Burma's summer capital of Maymyo. From there, it proceeds over hilly country for another 90 miles or so to Lashio, near the Burma China border. Maymyo itself was a very pleasant town and its cooler climate was enjoyed by all who could get away from the planes to the hills. The countryside through which the railway ran, both up to Maymyo and beyond, was lovely and spectacular, especially at the Gokteik Gorge, which is crossed by a steel trestle viaduct, 320' above the floor of the valley and 800' above the river which flows through a natural tunnel under the viaduct. In this hilly country, the scope for extending and enlarging the railway station yards in order to accommodate more or longer freight trains was somewhat limited. However, it was my job to consider the possibilities and make plans and estimates for Head Office to approve. At the same time, no doubt at some pressure on Burma and the Railway Management by Britain and China, it was decided to extend the railway from Lashio to the Chinese border and the Chinese would connect with the extension to Kunming. To carry our this project on our side of the border Sir John Rowland was appointed Chief Engineer and Cyril Kendall and John Hossack his Executive Engineers. The reconnaissance and survey work for this project was soon started. My work necessitated my being out on tour of the railway mainly between Maymyo and the end of the line at Lashio, for about 20 days a month. Occasionally I also visited my District Engineer in Mandalay but, as Mandalay was quite a few degrees warmer than Maymyo, these visits were somewhat brief. However, I recall on one occasion having been invited to stay with our friends, the McLeans, in Mandalay where Angus McLean was head of the Agricultural College. I decided to take my wife down by road from Maymyo, a distance of about 50 miles with some hairpin bends. I still enjoyed driving my Vauxhall Saloon car, which I had taken out to Burma after my home leave in 1936. Having lunched with our Mandalay friends and left my wife with them, I started on my return drive to Maymyo. I had driven about 15 miles when I was amazed to see an enormous snake cross the road some yards ahead of the car. On both sides of the road, the jungle was quite dense and by the time I stopped the car and got out my 12 bore shotgun, it had disappeared. I had seen many snakes in Burma, especially during the rainy season when the flooding of the countryside causes many of them to come onto the dry railway embankments. I went into the jungle to see if I could see it and managed to shoot it as it started to climb a tree. With the help of my servant, who was with me, we carried it and dumped it in the boot of the car. When back in Maymyo, I had it skinned and the very prettily marked dark brown and cream coloured Python skin, about eight foot long and nearly a foot wide, was sent away to be professionally cured. We received it back from the tannery six weeks later and a local cobbler made my wife two handbags a pair of shoes and a pair of slippers. Meanwhile, by December 1941, we were increasingly aware of the aggressive intentions and activities of Japan. For years they had been secretly building up their army and navy and their spies had no doubt full knowledge of the strength and weaknesses of their possible opponents. News of the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbour early in December astounded us but I can't say it depressed us as it meant that America would now be very much in the war. But the news was soon followed by the depressing and frightening news of Japan's invasion of Malaya and of the sinking of two British Battleships "Prince of Wales" and "Repulse" which Churchill had sent out to reinforce Singapore. Without an aircraft carrier to provide air cover, these ships had been attacked in the Gulf of Siam by Japanese dive bombers and torpedo carrying bombers and badly damaged and sunk with the loss of many lives. Soon after this calamity, we learned that the Japanese forces had started to invade Burma across the Siam/Burma border east of Moulmein and overcoming easily what resistance could be offered, they captured Moulmein by the end of January 1942. They had already started to bomb Rangoon, killing over 2,000 people in the first air raid and causing much panic and departure of local labour. The Government of Burma, anxious not to allow this serious and depressing news to become widespread over the whole country, resorted to "playing it down" and broadcasting the news that army reinforcements and planes were coming and the Japanese invasion would soon be stopped etc. We, who at that time were over four hundred miles from Rangoon and from the invading Japanese, could only try to carry on with our work. I have omitted to mention so far that in 1940 all Officers of the Burma Railways had been militarized. I find I still have the parchment document signed by Sir Archibald Cochran, Governor of Burma which reads;- "George the Sixth by the Grace of God of Great Britain and Ireland and the British Dominions beyond the seas, King, Defender of the Faith, Emperor of India, To our trusty and well loved Reginald Melville Ward Lowe, Greeting! We reposing especial trust and confidence in your loyalty, courage and good conduct, do by these presents constitute and appoint you to be an Officer in our Burma Auxiliary Force, Burma Railways Battalion from the 2nd day of August one thousand nine hundred and forty. You are therefore carefully and diligently to discharge your duty as such in the rank of Second Lieutenant or in such other rank as we may from time to time hereafter be pleased to promote or appoint you to etc." Being militarized meant that we, while continuing our normal work, had to also attend parades and lectures on bomb disposal etc. and also attend military camp and the rifle range and familiarise ourselves with the only automatic weapon available then which was the Lewis Gun. |

|

The Japanese forces having captured Moulmein and crossed the Salween river by the 9th February, thrust westwards, easily out manoeuvering and overcoming such resistance as our limited troops could offer. By the 20th February they had reached the Sittang river, the next major obstacle. The Sittang Railway bridge which is the only bridge over this river, is some 2,250' in length and the river flowing under the bridge is deep and fast. In order that military road vehicles could cross this bridge, the railway track had been hurriedly timbered over. The demolition with explosives of at least one of the 200' steel spans of the bridge to deter the Japanese advance had been intended by our army when they had retreated over the bridge, but an advance party of the enemy had reached the east end of the bridge, so in the confused fighting its demolition was carried out resulting in many of our troops and much equipment being lost.

Chiang Kai Shek offered to send his troops into Burma, his offer was accepted and so by the time the Japanese northern advance, still resisted by whatever British, Indian and other troops, reached Toungoo, we in Maymyo saw each day one or two train loads of Chinese troops travelling from Lashio to Mandalay and on southwards to meet the Japanese in central Burma and also towards the Shan States. The depressing news of the catastrophe at the Sittang bridge was somewhat ameliorated for us temporarily by the sight of these Chinese troops coming to help check the Japanese advance. The air defence of Rangoon depended on the few planes of the R.A.F. and an American Volunteer Group flying Blenheim’s and Buffalos and a couple of Hurricanes. They succeeded in shooting down several Japanese planes. In Rangoon the wives of British Officials who could leave the country by ship or by train to Upper Burma did so unofficially. We were still being exhorted officially over the radio to stay put as reinforcements were soon to arrive! Life seemed to go on much as usual in Upper Burma at this time. My wife was still with me in Maymyo and used to meet at the Maymyo Club the wives of other officials and to help the war effort these ladies would also meet at Government House to make whatever garments were said to be required by the troops! As the weather in Maymyo got colder at the end of the year, I found that I was gradually seizing in my joints, a sort of rheumatism and also some recurrence of the Amoebic Dysentery which I had some years earlier. The stiffness in my hip and knee joints at one stage got so severe that I could only walk slowly and with the help of two walking sticks. The local railway doctor had a sample of my blood analysed and told me that the stiffness was possibly caused by Amoebic cysts, due to my not having had a proper course of treatment some years earlier. Although due for some home leave, it was not possible to consider that now that the Japanese thrust into Burma was continuing, despite desperate efforts to stop it. To say that Burma was lacking the armaments is an understatement. I doubt if there was even an anti-aircraft gun in the country. In Maymyo we had dummy gun emplacements with 5" diameter bamboos to simulate guns pointing up into the sky. I don't know who the military authorities thought they were bluffing but it certainly wasn't the Japanese, who, no doubt, were kept well informed by Burmese "fifth column" activity. Despite the frequently broadcast Government exhortations to all Officials to remain at their posts and carry on as usual as military reinforcements were coming, the thoughts of most non-Burmese Officials whose wives were still with then, were concerned with plans to get the wives and their children out of Burma and with as little publicity as possible. During February 1942, as the Japanese advance westward neared Rangoon, there was a gradual deterioration of the position, despite General Wavell being saddled with the responsibility of defending Burma and General Alexander also coming to Rangoon. The first official civilian evacuation of Rangoon started by the 20th February and the wives of many of our Burma Railway Headquarters staff left Rangoon either by ship where possible across to India or by car or train to Upper Burma. Mrs Procter, wife of our Chief Engineer, with her two daughters and Mrs Milne, wife of our traffic Manager, with her son and daughter were among the railway wives and children who came up to Maymyo. The final evacuation of Rangoon accompanied by the explosions as the "last ditchers" carried out the demolition of the power house and the docks and the oil refineries to deny these facilities to the enemy, took place on the 6th March. As the" last ditchers," which included some Railway Officials, made their way northwards from Rangoon, they were lucky to get through the Japanese forces making their way towards Rangoon. Any escape from Burma from the port of Rangoon was now impossible so on the arrival in Maymyo early in March of the husbands of Mrs Procter (or Proctor) and Mrs Milne it was decided that their possible escape route was to go as far as possible by steamer up the Chindwin river to Kalewa and with the many other evacuees, to make their way as best they could by cart tracks and jungle paths for over 200 miles over the Chin Hills to Chittagong and thence by railway to Calcutta. This was to be no picnic and one had serious doubts that these ladies and their children could survive many days of walking up 8000' high hills carrying their own food supplies and the minimum of kit. However, as the only alternative was to stay and be killed or captured there was literally no choice. As a first step Mrs Procter, Mrs Milne and the children were taken by train from Maymyo to Ywataung via Mandalay and the Ava bridge, where they were joined by Mrs Cant, the wife of another railway Engineer. I took my wife by car from Maymyo to join them at Ywataung and we all continued by train to Monywa on the Chindwin river, where the party boarded the already overfull river paddle steamer. Although this happened fifty years ago i.e. March 1942, I shall never forget that evening when we arrived at the river port of Monywa and saw this very full steamer, which our wives and the children were to board. They were allocated a space on the top uncovered deck of the ship with no furniture or facilities. It was soon dark and the ship's electric lights were switched on. I don't think any of us had much to say and it was hard to pretend it was going to be a picnic. As the ship was about to leave to go up river, we said our goodbyes and the three of us; Eric Milne, Ernest Procter and myself, made our way by train back to Ywataung, from where, by car the next morning, I drove back to Maymyo. Although we had some doubts about ever seeing our wives again, we certainly did not voice these doubts. About a month or more previous to this, while life in Rangoon was fairly normal and the banks were functioning, my wife and I had decided that if she had to leave and go to India we should make some arrangements for her to have some money. So we instructed our bank in Rangoon (Grindlays) to transfer some money from our account to their Calcutta branch and open an account there for my wife. I also sent them a photograph of her so that they could recognise her if and when she arrived. A couple of days after my return to Maymyo, I was surprised to get a message from Messrs. Procter and Milne informing me that the ship on which our wives had left Monywa that evening, had returned with them, as the water level in the Chindwin had dropped so low, it being the dry season, that the ship could not get more than 60 or so miles up river without going aground. Also, owing to its carrying more than double its normal capacity of passengers, it had exhausted its supply of drinking water. It seemed we were now back to square one and some other means had to be found to get the wives and children out of Burma. Fortunately a few days later, we learned that some army Dakota planes were flying some supplies from India into Shwebo, so as the wives were not far from Shwebo, they were able to get a flight to Chittagong. Needless to say, we were all much relieved that this had happened and they had been spared that long and arduous trek. About this time, my friend Norman McAllister, Railway District Engineer at Mandalay, returned from India where he had taken his very ill wife to a sanatorium. He came up to keep me company, both of us now being without our wives. We went on tour together for a while in our respective inspection saloon carriages to carry out our jobs, which by then were becoming more difficult, as some of the work force, being Indian, were leaving to try to get back to India. This loss of labour was accelerated when the Japanese planes started to drop bombs on Mandalay and Maymyo. There was a big air raid on Mandalay early in April in which very many were killed and many houses set on fire. It must have been about the same time that three Japanese bombers flew, unopposed, over us in Maymyo and dropped some bombs on us. It was a very windy day, I remember, and I had walked down to the railway station to meet the morning mail train from Mandalay which arrived at midday. Just before the train arrived, the Japanese planes came and dropped their anti-personnel bombs, mostly between the station and the town. Some bombs also fell in the grounds of Government House. When I drove into the town after the raid, I saw that a few houses had been damaged and some people and animals killed. Another smaller air raid occurred on the morning of my birthday, 8th April, a few days later. The main effect of these air raids was the exodus from the town of the labour force and many shopkeepers. Conditions generally during April 1942 seemed to be gradually getting chaotic. Despite the help of the Chinese troops, the Japanese advance with their air superiority continued. Our postal and telegraphic services were also deteriorating and it was impossible for me to know whether or not my wife had got to India and where in India. She had had to leave behind almost all her clothes and personal possessions, which included the wedding present of a Moroccan leather bound beauty and jewel case, with its many silver fittings which I had bought in Harrods in London in 1936 and which she didn't want to lose, I had it packed and addressed to her care of Grindlays Bank. There was a slim hope of its getting to her if I could get it to the Chinese Consul in Lashio, who I had previously contacted, as there seemed to be a possibility that my eventual exit from Burma might have to be towards China if I happened to be on that side of the point where the Japanese troops cut the Burma/China road. The Chinese Consul was very pleasant and helpful and kindly gave me a permit, written in Chinese except for my name, to enter China if I had to. I still have this document. As regards the parcel which I hoped to get to India, I do not know what eventually happened, as with all our furniture and personal possessions, we never saw them again. |

|

Copy of the letter from the Chinese Consul in Lashio, addressed to A.P. Lui Esq., C.N.A.C. Lashio given to me in March 1942 in case I needed the help of the Chinese National Airways Company to leave Burma. It so happened, that I was eventually flown out from Myitkyina in May 1942 by a C.N.A.C. plane.

|

|

Towards the latter half of April, when much of the lower half of Burma was in the hands of the Japanese forces and our forces, together with the Chinese, were desperately fighting actions, every effort was being made by the Railway Staff to get the trains with evacuees into Upper Burma. One senior member of our Traffic Department, C.P. Brewitt, known to us as Pat Brewitt, who had won the Military Cross in the 1914/18 war and was now militarised with the rank of Lt.-Colonel, was very active in organising this withdrawal of railway personnel.