Sentry Page Protection

Please Wait...

Extract from The Rangoon Times Christmas Number, 1912

KALAW AND THE SHAN STATES RAILWAY

IMPRESSIONS OF A TRIP

by

J.B. Evans

KALAW AND THE SHAN STATES RAILWAY

IMPRESSIONS OF A TRIP

by

J.B. Evans

|

From Burma to England is a far cry, geographically speaking but in a land of paradoxes, such as this Province often proves itself to be, one can also say that it is not necessary to go to England to experience the climatic conditions which prevail in sunny Surrey. They are at Burma’s very doors. Many people know of the Southern Shan States; others again, but perhaps fewer, have heard of Kalaw. But the number of people who have even a nodding acquaintance with the health resort of the Southern Shan States is comparatively few indeed.

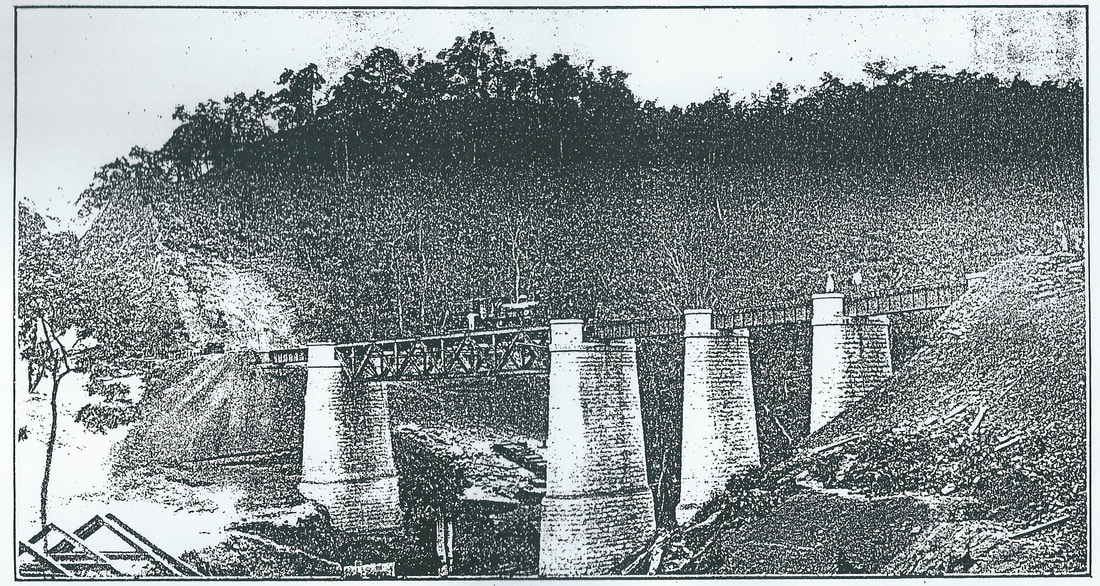

At the height of over 4500 feet in a slight depression on the great Salween Divide, it stands at the parting of the ways, so to speak, for all rivers to the west of Kalaw ultimately find their way to the Irrawaddy, while those starting even at Kalaw village wend their courses towards the Salween, the great river which forms the natural eastern boundary of Burma. Kalaw, it must be remembered, is of Burma, but not in it, for they are the domains of the Sawbwas and the indigenous peoples are the picturesque, but often times dirty, Shans. Hither, to this great entrepot of agriculture, come the bullock and mule pack trains and bullock carts in seeming myriads - much of the produce coming from as far afield as the boarders of China and Siam. It was to tap this great trade centre and to open up the commercial possibilities of these Shans that the Southern Shan States Railway project, a line of rail from Thazi to Yawnghwe at the head of Lake Inle, was mooted and the Indian Railway Board in 1909 sanctioned the construction of this railway at an estimated cost of 160 lakhs of rupees. Briefly put; after a number of surveys and alternatives the Burma Railways were, in 1910, asked to undertake its construction for the Government of India. The line is divided up naturally, into three sections ; Thazi to Law Choung ; Law Choung to Aungban ; and the final portion, the construction of which is still awaiting sanction, from Aungban to Yawnghwe. When one remembers that the Shan Mountains – the out-riding ranges – rise sheer out of the great plain of Central Burma, it will be seen that a stupendous task had to be faced by the constructional engineers. How they have surmounted the great natural obstacles will be recounted later. It was with the dual object of at least seeing Kalaw and forming some idea of the Railway project’s progress that the writer ventures on the journey to Kalaw at the tail end of the monsoon in September, when the principal means of transport is the jolting bullock cart. And where the route for such lies forty miles through gorges, yet climbing steadily all the time until a height of 5,000 feet is reached, the task of commissariat is not one which can be lightly undertaken. It is a truism that an army marches on its stomach, and that it is, in consequence, no speedier than its slowest transport wagon. Therefore of what avail is it, if one is stranded in one of those haven of rest and comfort (!) a P.W.D. bungalow with the bullock carts containing supplies, servant and cook, a day’s march behind? Thus there was this anomaly to be faced – a train journey of over 325 miles, accomplished in eighteen hours ; and a journey up the hills of 40 miles or so, taking nearly two and a half days to accomplish. Yet that is the prospect at present confronting intending travellers to or from Kalaw and Rangoon. Small wonder then, it is not, that Kalaw’s delightful and bracing qualities as a health resort are, so far, unknown to the vast majority of sojourners in the Province? At Pegu, where welcome dinner was to be had, it was raining the monsoon’s hardest. Dreary, flat and flooded fields of a most unlovely description were at length blotted out by the drizzly night ; and troubles and ennui were soon forgotten in sleep. Sleep did I say? Now and then through the night, at one or other station en route, a lantern would flash in upon one, or else the broken sleep would be rudely disturbed by a raucous refreshment seller with his monotonous “Bilat-ye.” At Toungoo, of course, it was still raining. Then at last came sleep, until the morning sun, which shone in through the chinks of the Venetian windows, was a reminder that chota-hazri was near. Thazi was reached and breakfast there disposed of. Everywhere, as far as the eye could see, the country looked parched. I was informed that rain this year had been conspicuous by its absence in and round Thazi. The fear present in many of the inhabitants’ minds was famine. Irrigation tanks were at very low levels indeed and their irrigating capacity considerably weakened in consequence. One does not realise what a crying problem the supply of water is until the dry zone of Burma is reached. Thazi has the reputation of being one of the most torrid places in Burma. Well did it sustain its reputation the morning the writer reached it. Boarding the Shan Sates train, which was to take me over the first twenty-three miles of the journey eastward, the sight disclosed was distinctly depressing. Along the single set of rails from Thazi to another tongue-twister, Payangazu – on either side – a howling waste of scrub, cactus plants and parched herbage met the eye, instead of the smiling green paddy fields which are the usual feature, even of this inhospitable zone at that time of the year. The train, as on many branch lines, was quite happy-go-lucky in its homeliness. Let him who asserts that there is no humour in a railway train pause ere he makes the assertion and take a trip from Thazi to Yinmabin. With a style almost Bohemian, and distinctly Oriental, passengers boarded and left the train as if it were a street tramcar. On through and the cactus and scrub it crawled ; Kyatti was passed, then Hlaingdet and Payangazu – all the time the track running parallel to the P.W.D. road, which for years has been the great trade route to Taunggyi. Hills and imagination go together ; therefore can it be wondered at, that, in the main, the inhabitants of the Netherlands are lethargic – even stodgy? At length the dreary curse provoking flats were left behind ; and at Kywedatson the foothills began. Flagging interest in the scenery was awakened as the ascent of the first ghaut to Yinmabin (1200 feet above sea level) was commended. The section of railway between the above mentioned points – short though it is – is yet a marvelous triumph of engineering over seemingly insuperable obstacles of nature. In and out the railway winds its way, a maze of sinuosity’s. Cutting through virgin forest and thickly wooded hillsides and rising all the time, it passes over numerous bridges and viaducts which look down on deep choungs and dried up watercourses, disclosing a panorama which cannot fail to delight the eye – were the sun not so terribly manifest. After negotiating a high viaduct, the train sweeps round on a rising gradient ; and passing through a deep rock cutting, which momentarily appears as if it would fall in and crush the audacious little piece of mechanism which pierces daily through its heart, the line emerges higher up the hillside, having described a sweep of nearly three quarters of a circle. Yet, deep cuttings and the hard bluish rock, notwithstanding, not a single tunnel is met with. The winding is at last at an end and the terminus of the completed section, Yinmabin (or Tagundine,) is reached. From this latter place to Lebyin, about twelve miles to the south-east, the whole country bears – and deserves – the reputation of being one of the most pestilential fever zones in the whole of the province. The quinine prophylactic treatment is therefore a paramount necessity, at least so long as the railway to Kalaw is unfinished. If there was no rain at Thazi, the deficiency was amply made up by the downpour at Yinmabin. So needs must when the weather drives and I decided to put up for the night at the P.W.D. Inspection bungalow. With the coming of the railway to this part of the world, there has arisen, mushroom-like, the inevitable collection of huts and the indispensable bazaar. Pathans – the workers in stone – rub shoulders with their more indolent neighbours, the Burmans ; now and again quaintly dressed Shans mingle with natives of India ; and here in this small compass is crowded as polyglot an assembly as the most captious would wish to see. The tramp of many feet and the interminable procession of bullock carts have reduced the P.W.D. road at Tagundine to a veritable quagmire ; the rain, of course, assisting. At length the rain clouds cleared and shoals of mosquitoes and flies meandered about in the steamy atmosphere seeking whom they might infect – certainly not a place for European habitation, and away in the distance towered the blue mountains, somewhere on the summits of which nestled Kalaw. I was – shortly stated – forty miles from health, with another night’s stay at a place, the reputation of which for fever was worse than Tagundine. Making an agreement, through the medium of the loquacious thugyi of the village, for the bullock cart necessary, I learned to my dismay that the journey to Kalaw necessitated two nights on the road or rather at the P.W.D. bungalow. Bullock carts may be sure as a means of conveyance, but they are notoriously slow. The “jarvey” too, who had been secured for me, was, if possible, the slowest in upper Burma ; but again “needs must.” So at daybreak the next day this be-loongyied human tortoise and my bohea started out, and a little later I followed on foot. The road to Pyinnyoung is a fairly good one, winding as it does through level country, for the most part virgin forest and jungle. Walking at first was a pleasure, later a task and eventually an act of heroism. The sun’s rays beat down piteously, while a mile or so ahead of me creaked and jolted the “express,” going at a very even speed of two miles an hour. At length, after passing cavalcades of bullock carts, the river Mytthe was crossed. Pyinnyoung bungalow – and tiffin, al fresco of course – hove in sight. It is at such moments even the least scripturally inclined can realise the aptness of the description: “The shadow of a mighty rock in a weary land.” The mighty rock in this instance was the Inspection bungalow perched up on a clearing and looking down towards a cavernous gorge through which rushes the river Mytthe. It was, one could imagine, such a picture as this which Coleridge conjured up in his wonderful descriptive fragment “Kubla Khan” – ... where Alph the sacred river ran, Through caverns measureless to man, Down to a sunless sea. Nature has not done things by halves in the wonderful Shan mountains. At length the noonday halt is over and the second ten-mile stage has to be negotiated. Be he artist or poet of superlative merit, the scenery from Pyinnyoung through the heart of the mountains would tax his powers to the utmost. The writer’s description must, therefore, be of the most halting and scrappy nature, not being gifted with the brush of a Corot, or the word-imagery of a Keats. For three miles or so towering mountains with precipitous sides enclose a deep valley - gorge were the more appropriate term. Not a breath of air is stirring and the heat is stifling. But the panorama unfolded more than compensates for these temporary discomforts. Down through the gorge rushes the river Mytthe. The direction of the stream puzzles one at first ; it has the appearance of flowing at a rapid rate straight into the heart of the mountains and contrary to the course of Nature. Yet it is not so. The stream winds through this, the Kugytaung Gorge, dashing here and there in a turbulent fashion over the blue rocks until at mile 34, out of sight of the road, it joins the Wetpyuye Choung and together they flow through another of the deep valleys ; until at length, emerging into the plains of upper Burma, the large stream pours its contents into the Irrawaddy. At this stage of the journey the scenery is wild in the extreme. Trackless and precipitous mountains shut in a gloomy valley, while held in by retaining walls, the road winds interminably, looking down on the turbulent torrent, sometimes fifty, sometimes a hundred feet below. What a contrast to the dreary, rain-sodden flats of the Delta? Foliage runs riot and all kinds of trees are seen. But there is something lacking ; the intense silence is only broken occasionally by the booming of the torrents and the whirring of crickets. Birds nowhere add to the harmony and “though the sedge is not withered by the waters edge, yet no birds sing.” Ominous thunder clouds are gathering and the heat becomes more and more oppressive. Then down falls the rain and the steep furrows, which separate the mountain sides, soon are transformed into channels down which dash roaring earth-laden torrents crashing across the roadway, over the retaining walls and falling at length into the river beneath. Thunder reverberates from peak to peak and much against my inclination I am forced to take refuge in the bullock cart. In a driving thunderstorm the sleepy-eyed bullocks jog along and with aching bones my only wish is for the journey to end. At length from a semi-slumber I was awakened by the “boy’s” voice calling “Durwan.” Then a brief space and the flashing of the latter’s lantern announced the completion of the second stage. Perched up off the roadway, hemmed by tall trees and shut by the mountains, Nampandet bungalow, eerie and ghost like as it seemed, was yet a veritable haven. Hunger appeased, sleep came at length and with it the registration of a vow to leave all future trips to Kalaw until the completion of the railway. But next morning when the sun, peering over the mountain ridge to the east, dispersed the low hanging mists of the valley, there was a different mood and hope sprang eternal. The stiffest stage of the climb lay before us all. Very soon the Wetpyuye Choung was crossed and then the road from Nampandet – now in Shan States territory – began to climb the mountainside in a most deliberate fashion. Up and up it wound in a series of rounded zig-zags, nearly boxing the compass in its gyratory course. At every turn of the road the prospect unfolded became more magnificent. Range after range of forest clad mountains met the eye and far down below one could see the road which an hour or so earlier seemed an elevation in itself. In eleven miles the road rises of 2000 feet. Yet through the gradient is a trying one, it does not present great difficulties. Here and there mule tracks provide short-cuts through the forest – but such were not for me. At turns of the road, bullock carts coming in the opposite direction made passing difficult for my Burman driver. The temperature was now becoming perceptibly cooler and high noon saw our little caravanserai at Wetpyuye, 3200 feet up. The bullocks now being about used up, further progress that day was impossible as, although Kalaw was but a little over nine miles away, a further rise of 1500 odd feet had to be negotiated. A more delightful situation than the bungalow at Wetpyuye could not be imagined. Facing the road, it looks down from a lofty eminence on a deep valley and takes into the picture the purple mountains away to the north and north-west. The change of temperature here is very marked and that night I was seated before a huge log fire looking over a 1907 volume of the “Tatler.” Tempora mutantur! But dawn – mystic and beautiful – at Wetpyuye is a spectacle which the traveller should on no account miss. The moon was just setting and a ghostly grey light was stealing over the sky in the east. Down below the valley lay, still hidden in the darkness and obliterated by a pall of mist through which like islands in a great white lake the peaks broke through. Then peak after peak became suffused with sunlight, the mists dispersed and once more we were on the high road. Equally picturesque is this last section of the journey. For a mile or so the road skirts a small valley in which repose emerald green paddy fields. Then curving in and out of the mountain chinks it begins to climb once more. The vegetation is now considerably changed, the trees remind one more of home than of Burma. The subtle odour of the pine pervades the air. At long last Kalaw is made and the dak bungalow on the hillside, half stone, half brick, with hearths and chimneys, reminding one that the heat of the planes has been left behind and that cool evenings and chill mornings are to be expected. Kalaw itself can be described as a halt in the mountains, as if Nature, tired of her stupendous works, rested while. The hills around seem puny until it is recalled that they are extensions from a height of over 4000 feet. Originally a Shan village, there is nothing particularly noteworthy about Kalaw itself in appearance. The village is the usual collection of kutcha huts and stalls and un-drained alleys. In the centre of the hollow is a hpoongyi-kyaung and numerous ruined moss grown pagodas. On the south-eastern side the red laterite cuttings at the foot of the hill are harbingers of that civilising agent – the railway. Through the village traverses the metalled road to Taunggyi. The mountains are girdled with pines and trees indigenous to such a height in the tropics and the fresh pure air of the mountains is invigorating in the extreme. Kalaw is at present a perfect Babel of tongues, the railway construction causing an influx of skilled Chinese and Indian workers. But already the place is growing. European bungalows, white and trim, peep out from among the trees on the hillside above the railway cutting. These are the railway construction engineers bungalows and in the gardens around these homes are all kinds of blossom – snap-dragons, roses and the like. In front of one of these bungalows I saw dahlias and cream chrysanthemums flowering in close proximity to each other. The coterie of Europeans is small but it is axiomatic that where two or three of such are gathered together out East, there you have a club. The Kalaw Club is, however, a club of the right kind – a large family circle, where, after the day’s work is over, the sahibs and memsahibs of the station meet to chat, play bridge and read the periodicals. There are also two nicely laid out tennis courts in front of the model club house. Having had several evenings’ experience of the hospitality extended to visitors at the Kalaw Club on the hill-side, the writer can vouch for the feeling of comfort engendered by a chat, whilst seated in front of a roaring log fire – for the nights are crisp and chill in Kalaw. Hard by are the railway engineers’ offices while on the other side of the valley, across the future maiden, are the offices of the Kalaw Sub-division of the Public Works Department. One meets many contrasts of old and new on the Kalaw road : the mule train, ages old, the equally ancient bullock carts and finally the fussy puffing motor bikes and motor cars – three stages of transport. In a short while the railway will supply the fourth and complete the circle. The hills around Kalaw are mostly red laterite and viewed from whatever coign of vantage, the Shan station is distinctly a place “where every prospect pleases,” though Bishop Heber’s corollary does not follow as a natural consequence. The dak leaves daily up to Taunggyi and down to Thazi. It is a quaint sight to see pony-post on its journey. Kalaw, as stated at the outset of this articles, is a great entrepot. Hither come bullock and mule loads of potatoes, vegetables, fruits, onions (in plenty) garlic, paddy, flour and provender of all kinds and here the pucca Eastern barter is carried on. The burra bazaar is held on a Tuesday, the stalls being set up on a hillside at the western end of the village. The place was a medley of languages and peoples, their voices raised in banter and chaff. Kalaw is not without its share of the monsoon rainfall but the temperature is at all times bearable and balmy. The nights, even in the hottest months of the year, are cool and fresh and the mornings – well a Kalaw morning is like nectar in its purest. In the cold months fires are an imperative necessity, as the temperature during such a season often register a temperature of zero, the heat of Rangoon being unknown even in the so-called hot months. No better index of the salubrity of climate is to be found than the European children here. A more happy rosy-cheeked and healthy collection of children it would be difficult to find, even at Home. The pride of Kalaw at the time of my visit to the station was the “Kalaw baby, “ a bonny little girl, Gertrude Rouse, the first European baby born and brought up at Kalaw. The little daughter of Mr and Mrs Rouse looked a chubby picture of health and was the best testimonial that Kalaw could have had. The place itself has been plotted out as a future Hill station with roads, house sites, polo ground etc. At present the work is well advanced of clearing the native village in the centre for the dual purpose of making a maidan and safeguarding the water supply but until a better water supply is assured the development of the place as Hill station is likely to be retarded. Of course, there is the Ye-e valley to be tapped, but that is in the future. The road leads over the mountains through woods and pine forest to Thamakan at mile 72-7, where at a height of 4240 feet this village is located. The route is delightful for cycling. At this point the depression formed by the Inle valley begins and the metalled track winds down to Heho, ten miles further on, where the height above sea level falls to 3800. Along the plain the fall still proceeds until Sinhe in the hollow is made at mile 95-1. To reach Taunggyi from this place, much the same procedure is followed in negotiating the hill, as already noted from Nampandet to Wetpyuye, only trees are less frequently seen. The gradients, as can be expected, are somewhat steep, as the road rises 1675 feet to 8½ miles. Taunggyi, the headquarters of the Executive Engineer of the P.W.D., Taunggyi Division, stands at an eminence of 4675 feet. The Heho plain, it might be mentioned, is a succession of rolling downs and the trees and consequently the rainfall, are much less in evidence that at Kalaw.

The pride of this portion of the country is a large tract of water known as Lake Inle, a gem of silver in the mountains. It provides the sportsman, if he wish, with duck shooting, the decoy boats being cleverly constructed by the Shans. The strange feature of this lake, particularly noticeable, at the Yawnghwe festival, is the method of propulsion which the boatsmen adopt. In their long dug-out canoes they travel along at an amazing speed in their following way – standing up in their frail looking crafts the boatmen lean towards each other in pairs and rest their adjacent shoulders together. With one leg entwined round the long paddle and the other resting on the side of the boat, they urge the craft forward with great celerity – a really marvellous feet equilibrium. South of Taunggyi and at the northern end of Lake Inle is Ywanghwe, the surveyed terminus of the Southern Stan States Railway. This station is an important centre. Here is the Government School for the education of the children of the Shan Chiefs. Here also the Sawbwa of Yawnghwe holds his Court, guided by the advice of an officer appointment by the Government of Burma. At the eastern shore of the lake, whose waters debouch into a tributary of the Salween, is Fort Stedman, a former military outpost station. There are two ways of getting to Kalaw from Thazi. One is by the P.W.D. road, already described, the other is by mules along the railway cuttings. This is a highly interesting route and gives an insight into the almost insuperable task the engineers have had to face. There are excellent rest-houses at frequent intervals up the Pinmon valley from Lebyin the present rail-head though Yinmabin is the actual train terminus. Before describing in detail the sanctioned and completed sections from a railway point of view, it is interesting to note that the branch from Yinmabin to Kalaw – or rather to Aungban at mile 70 – supplies an exception to the generally accepted axiom that where a good road is possible there also a railway can go. There is not the slightest doubt that considering the climb the frequent slips and the havoc of the mountain torrents, the condition of the road which zig-zags in the amazing fashion described, up the Wetpyuye ghant, is a tribute to the skill and energy of the Public Works Department who are responsible for the care of this important means of communication. Repairs are being continuously carried out, especially on the heavy gradients. But the real point is that the Nampandet-Wetpyuye route is absolutely impossible as a railway route. Apart from the enormous cost, the sharpness of the curves would baffle all known engineering skill and the frequency of slips and wash-outs would nullify the efficiency of the line during the rains, of which this district gets an ample share. Thus, if there were no alternative route, the Southern Shan States Railway project would be as dead as Queen Anne - and the latter’s demise is quite generally accepted in Burma. Luckily, however, for all concerned, there is another route to the uplands – an excellent one too, as it transpires – through what is known as the Pinmon valley. To explain the position of this to an outsider it is necessary to detail the seeming maze of mountain ranges here met with. It will be recalled that at Yinmabin the railway and road routes part company. The road goes in one direction and enters the Kugytaung George, already described, at mile 31. The railway proceeds in a somewhat south-easterly direction and the first projected station is at Pyinnyoung – five miles nearer the source of the Mytthe river than the Pyinnyoung on the P.W.D. road. From Yinmabin to the railway [at] Pyinnyoung and thence to Lebyin is virgin jungle and forest and this tract has richly earned the reputation of being a fever zone. Statistics in the keeping of the Railway Company effectively prove this. Villages are few and far between – in fact the country has hitherto perforce been a “no man’s land.” One doubts really whether this flat inter-space, before the mountains are reached, will ever be fit for human habitation and settlement. From Lebyin the railway route continues south-east and now runs parallel to the road on the other side of the mountains. At this, the entrance to the Pinmon valley, gorgeous forest and mountain scenery delight the eye. Then the railway begins to climb the steep slopes in the manner which has made Maymyo accessible. Zig-zag breaks in the forest scenery demarcate the course of the first and second reversions, engineering feats in themselves. The next two and best reversions of this section are met with at Pinmon and a height of 4470 feet is reached. A magnificent panorama meets the gaze. At the head of the narrow valley towers the Elephant Mountain, Sintaung, at a height of 6022 feet. Under its aegis lives Mawton, at which stage the line makes a sweeping horse-shoe bend, and travels east to Kambani. This latter place is the show point of the section, for after emerging from the only tunnel, a vista of a circle of tall mountains – the saddleback of Burma and the partition of the Irrawaddy and Salween basins – is unfolded. One of the freaks of nature, a huge cup-shaped depression, called a “punchbowl” – Devil’s or otherwise according to the taste and fancy of the traveller – is here observed. To draw an adequate word picture of the wonderful depression is an impossible task and as it is not the object of this article to attempt impossible feats, I will content myself with a brief description of it. Like a gigantic silent sentinel Sintaung overlooks the “punchbowl” at Kambani. Some idea of the magnitude of this natural basin can be gathered from the fact that its larger diameter is at least eight miles and the lesser, four miles. The lay of the land here is rather mystifying. The streams apparently should flow northward, but it is averred that they do not, but cross subterraneously or otherwise into the adjacent Pinmon valley, feeding the streams which sometimes run – and sometimes do not – through it. The survey maps detail a general direction, but, the land Records Department notwithstanding, there is much to be explained as to the destination of the waters collected by and flowing from these enclosed basins. The summit of the ridge is at Kambani and thence forward there is a slight drop in the easterly direction of the cutting to Myindaik and at Kalaw the line meets the P.W.D. road to Taunggyi. But having once parted company with the foot route, the line seems rather coy and shy of renewing the acquaintanceship. The P.W.D. road continues a slightly more northerly course, while the railway passes Kyegon and finally at mile 72, Aungban, the terminus of the second section is reached. If and when the surveyed and last section to Yawnghwe is constructed the line will cross the Myelat plateau at Heho and developing down the ghaut into the Inle depression, its terminus will be at Ywanghwe. The project of a railway to these parts from the plains of Burma is no new one, in fact Government surveyors have been dallying with schemes and surveys since 1901. The routes and estimates submitted by them were various in character and the estimates were to a large extent approximate indeed, to the nature of the country. Being virgin jungle and forest, it was in a great measure a matter of conjecture as to what engineering difficulties would be met with. However, the general consensus of opinion went to show that any possible line of railway up the Mytthe and Wetpyuye Choungs would be of such a costly nature as to be prohibitive. The present route and scheme is in the main based on the estimates and survey conducted under the superintendence of Mr G. Richards, the then Chief Engineer of the Burma Railways in 1907-08. In this scheme Yawnghwe was selected as the ultimate terminus. In September 1909 the Government of India sanctioned the construction at an estimated cost of 160 lakhs of rupees and in December of the same year and immediate expenditure of Rs. 50,000 was sanctioned by the railway Board at Simla, the Burma Railways then being asked if they could proceed with the construction during the following year. Then a further expenditure of 1½ lakhs was agreed to and also an additional five and a half lakhs, if the Company would spend that amount in 1909-10. In February 1910 the Secretary of State sanctioned the construction of the line on the metre gauge, after the “pros” and cons” of this gauge, compared with the narrow 2 feet 6 inch gauge, had been fully weighed and discussed. As an instance of the heavy cost of surveying, it may be stated that up to that time the amount expended on survey work amounted to Rs. 5000 a mile. The first estimate submitted was for 23 miles of single track railway from Thazi to Tagundine on the Yinmabin ghaut. Though much of this was on the level, yet from mile 18 the work was of an exceptionally heavy nature. The route finally adopted lies for the first 35½ miles, until the Law Choung crossing is reached, in the Civil Division of Meiktila. But from this point to near Myindaik at mile 57½ it runs through the Yamethin District. Thereafter it is entirely in the domains of the Sawbwas of Thamakan and Yawnghwe, respectively. The maximum rise is from 526 feet at Thazi to 4595 feet between Kambani and Myindaik. The mountain sides, even up to the Pinmon valley, have not rendered the task of the constructional engineers easy, as they are of a very broken nature. The Mytthe river, which runs in a parallel direction to the Samon from south to north, emerges into the plains near Thabyedaung on the Burma Railways. Between the valleys a ridge of hills has to be crossed, the summit level at Tagundine being 1320 feet. The whole of the country from the foot of the Yinmabin ghaut to Myindaik is covered with dense malaria-breeding jungle and forest and in addition to its unhealthy nature, offers countless problems to the engineers. Small choungs furrowing the mountain sides, beetling cliffs and queer contours have, however, been conquered ; and next year will see the second section as far as Aungban opened to traffic. The whole country to Kambani, with the exception of straggling hamlets here and there composed of kutcha huts and inhabited by people distinctly nomadic and primitive in habits, is practically uninhabited. Water is scarce en route. As stated however, the fortunate discovery of the Pinmon valley has lessened the expenditure somewhat. For the greater portion of this section a gradient of 1 in 25 has been adopted, the other ruling gradient of the line being 1 in 40. This latter is the gradient on the first ghaut until the summit at mile 22 is reached. The station at mile 23 should have been named, in the ordinary course of railway nomenclature, Tagundine, but as there is a station of similar designation on the Burma Railways it has been re-named Yinmabin. The Mytthe Choung has been spanned by a long bridge 35 feet above the level of the bed of the stream. Lebyin is 1515 feet above sea level and thereafter there is a continuous rise until the summit tunnel at mile 56. From Myindaik the survey originally allocated the line along the Ye-e stream, but owing to the Local Government deciding to conserve the Ye-e valley water supply for the possible future Civil station of Kalaw, the alignment has been changed somewhat It is intended to make Myindaik the headquarters or “homing” station of the line, as it is in a superbly healthy situation and there is an excellent supply of pure water. Aungban, the terminus of the second section at mile 72 is a very important trade centre, standing as it does at the junction of the principle trade routes. The work has been carried out under the superintendence of Mr H. Hughes, Chief Engineer of the Burma Railways and the constructional engineers, Messrs. Webber, Davidson, Rouse, Cookson, MacDonell, Bevan, Willcocks and Doog. At the time of writing this article Messrs. Webber and Rouse were stationed at Kalaw ; Davidson and MacDonell at Yinmabin ; Cookson at Kambani and Bevan at Lebyin. The first section cost has been: Division 1. Thazi to Yinmabin (33 miles) about Rs. 35 lakhs Division 2. (estimated) Yinmabin to Lebyin, (mile 35.52) about Rs. 26 lakhs Division 3. (estimated) Lebyin to Aungban (mile 72) about Rs. 81½ lakhs The estimated cost of the final section from Aungban to Yawnghwe is about Rs. 56 lakhs. Thus it will be seen that the grand total of expenditure (actual and estimated) on the line from Thazi to Yawnghwe is nearly Rd. 1,99,00,000 which works out at Rs. 1,91,000 odd per mile. And after all is done : what then? That the line will add vastly to the opening out of the Province is certain. The agricultural possibilities are untold. The Myelat plateau is undeveloped ; though there is a certain amount of paddy cultivated it is true. The Inle Valley is admittedly very fertile and some wheat is grown. The climate is equable and there is no reason why British settlers, agriculturally inclined, should not take up land there when railway transport is assured. There is no reason, from a settler’s point of view, why the delightful Southern Shan States should not be made a great granary and a cattle-raising centre – in fact the Rhodesia of Burma. |