Sentry Page Protection

Please Wait...

The Second A-B War - 1852-1854

extracts from

A History of Rangoon

by

B.R. Pearn

published 1939

press ctrl + f to search this page

extracts from

A History of Rangoon

by

B.R. Pearn

published 1939

press ctrl + f to search this page

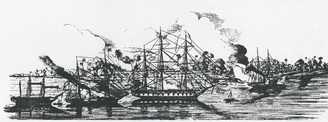

Scene on the Rangoon River, Easter Sunday, 1852

|

..... In June 1851 the 250 ton barque Monarch, Capt. Robert Sheppard, came into Rangoon from Moulmein. On the second day after her arrival a complaint was preferred before the Myowun by a Chittagonian named Hajim, who asserted that during the voyage his brother Esoph, a Pilot, has been thrown overboard by the Captain and had been drowned.

The Myowun ordered the arrest of Sheppard, who defended himself with the statement that the Pilot had run the ship aground and then being terrified of drowning had jumped overboard of his own accord and succeeded with the aid of a piece of timber in reaching the shore. The defence was not accepted and Sheppard was convicted. One of his crew, it was said, was beaten to force him to give evidence against his Captain. Sheppard was detained under arrest until security had been given by some of the merchants of the town and when security had been given he was required to pay a heavy fine. A further charge was then brought against him by yet another Chittagonian, Dewan Ali, who also claimed to be a brother of the Pilot. The complaint this time was that Hajim had had five hundred rupees with him and that sum was now missing. Though acquitted by a panel of assessors, Sheppard was further mulcted in this sum and had in all to pay Rs. 1,005. He reported the matter to the Commissioner of Tenasserim Division, and made a claim against the Burmese Government for the loss incurred in respect of the fines and of the delay of eight days to which his ship had been subjected. Two months later, in August, the Champion, a 410 ton ship, arrived from Mauritius and the Captain, Harold Lewis, was charged with the murder of one of his lascars who, according to Lewis himself, had died a natural death shortly before the vessel reached Rangoon. The charge was made by two Bengali coolies who had stowed away on the ship and was supported by some of the crew, who deserted and made an appeal to the Burmese Authorities for the recovery of their wages. Lewis like Sheppard, was arrested and was able to secure his release only on payment of a fine of Rs. 700. He likewise made a complaint, this time to the Governor General’s Office in Calcutta. In the past the Company’s Government had taken the view that British subjects who traded with Burma did so at their own risk, but Lord Dalhousie, now Governor-General, was disposed to adopt a different policy, although at the same time he had no desire for a rupture of relations with the Burmese Government. An enquiry was held by his order and the damages, which Sheppard and Lewis had assessed at Rs. 19,200 were cut down to a total of Rs. 9.200. Commodore G.R. Lambert, in H.M.S. Fox, was then ordered to Rangoon with the Company’s war-steamers Tenasserim, Capt. Dicey, and Proserpine, Capt. Brooking, to demand reparation. Capt. Thomas Latter, 67th Bengal N.I. and R.S. Edwards attended as interpreters. The Commodore’s instructions were that in the event of failure on the part of the Myowun to make redress, the Burmese King was to addressed by letter. The Commodore arrived in the port on the 25th November and was at once approached by some of the foreign merchants who stated their grievances, which they subsequently put in writing, complaining that instances of injustice and oppression were “of daily occurrence” and that the least protest was liable to involve heavy punishment. It appears that the first of these complainants to board the ship was May Flower Crisp, now, as ever, in trouble. Troublesome though he was, he cannot but be admired for his effrontery. “That man”, stated Lord Ellenborough, “as soon as he knew of the probability of war, freighted a schooner with arms and sold them to the Governor of Rangoon. When the Governor refused payment for them he had the effrontery to go to Commodore Lambert and complain of the injury inflicted upon him... The Governor of Rangoon offered in consequence £100 for that man’s head and I confess I should not have been deeply grieved if he had got it.” The Myowun, learning of the action of Crisp and others, forbade any further communication between the inhabitants of Rangoon and the warships and probably alarmed at the anchoring of the Fox close to the old town, required her to be removed to the position assigned to mercantile shipping. On the 27th a letter addressed to the Myowun was taken ashore by Capt. Lambert and another officer, these officers went to the new town to the Myowun’s residence and there they complained they were received with incivility, for they were kept waiting and when the Myowun did at length appear he was dressed in his shabbiest clothes and was smoking a cheroot. The letter, which was read aloud first in English and then in Burmese in the presence of the Myowun and of the European merchants who had been summoned to attend, stated that in view of the complaints received from the merchants, the reparation which was to have been demanded was clearly inadequate and that therefore further orders from the Governor-General would be sought. The Myowun was naturally disturbed at the unpleasant situation which had arisen and showed himself anxious to be conciliatory but the officers refused to hold any further conversation with him and returned to their ship. The next day a number of officials visited the Commodore to assure him that any acts of injustice which might have occurred had been indulged in without the Myowun’s knowledge, but they were given in return a letter addressed to the King seeking the removal of the Myowun from his office. The Proserpine was then sent to Calcutta to report the situation. The Myowun assembled a force said to have numbered ten thousand men and armed one of the King’s ships which was lying in the port. The troops so assembled, it was complained, received no pay and were dependent on robbery for their food and in view of this and of the generally alarming nature of the situation, the European inhabitants assembled at the house of a merchant called Birrell, who erected a bamboo flagstaff on the roof so that he might communicate by signals with the warships and also placed a small two-pounder cannon on the landing of the house. The Myowun regarded these acts, quite properly, as breached of the law and insisted on the removal of both the flagstaff and cannon. At the same time, the situation of the foreigners was certainly precarious. The Burmese soldiers, it is said, frequently threatened the English residents with their muskets and an American missionary, Kincaid, suffered ill-treatment while going to visit the ship where his family had taken refuge. It seems, however, as if an outbreak of war would be avoided, for the King’s reply to the letter of complaint was pacific and conciliatory, expressing hope that there would be no breach of friendship and announcing the removal of the Myowun. On the 4th January 1852 the new Myowun arrived and though the old Myowun was given a triumphal farewell, when Edwards was sent on the following day to enquire when it would be convenient for a statement of the claims for reparation to be brought, he was well received, the Myowun expressed his willingness to receive a communication next day and further showed his anxiety to be friendly by removing the embargo on communication between the town and the warships. On the 6th, therefore, a deputation consisting of Capt. Fishbourne of the steam-sloop Hermes, Capt. Latter and two other officers, went to the new town bearing a letter asking for a settlement of the claims and proposing the re-establishment of the Residency. The outcome of this deputation was most unfortunate. Edwards went ahead to give notice of their approach, but when he reached the Myowun’s house, “at the foot of the outer steps, one of the Governor’s suite drew his dagger on him and threateningly asked him how he dared thus approach the Governor’s house.” Edwards on being admitted, informed the Myowun of this occurrence, whereupon “the Governor sent for the offender and punished him in the presence of Mr Edwards in the usual Burmese manner, namely, by having him taken by the hair of his head, swung round three times, his face dashed to the ground, himself dragged by the hair and pitched downstairs.” When, however, Edwards said that the deputation of officers was approaching, the Myowun showed himself unwilling to receive them, for he had expected that the Commodore would come in person. In the absence of the Commodore he was prepared to accept any communication brought by Edwards, whose rank was definitely inferior to his own, but was reluctant to grant an interview to officers who, though his inferiors from the Burmese point of view, regarded themselves as his equals and would behave accordingly. He was he told Edwards, afraid that they might “behave discourteously and not according to the rules of etiquette,” that is to say, he feared that his awza or authority would be diminished in the eyes of his people. Meanwhile the officers had borrowed horses for the two mile journey from the river bank and arrived in the new town at about midday. When they reached the Myowun’s residence they were requested to dismount out-side the compound, but, ignorant of Burmese practice and assured by Capt. Latter that this request was intended as a deliberate insult, they took offence and insisted on riding in. This behaviour apparently hardened the Myowin’s determination not to receive them and they were informed that he was asleep, though at the same time Edwards was again informed that the Myowin was willing to receive a communication through him. While this argument was going, on, the officers were invited to “go and stand under the shed, the place where the common people usually assembled,” but seeing this a further insult they refused and after waiting for some time in the sun they returned to report to the Commodore.“This conduct,” says a contemporary writer (Baker) “left no room for doubt on the score of the tone the new Governor intended to adopt,” and it was in this spirit that the Commodore acted when he was informed what had happened. In reality, however, the Myowun had, so far as can be seen, no desire for a breach of relations, just as Lambert’s officers did not realise that they had committed a breach of good manners by riding into the Myowun’s compound, so equally the Myowun, who had had no previous experience of dealing with foreigners did not realise that no offence had been intended and in declining to receive the deputation he forgot that Lambert had received in person every official, of whatever rank, that had come to his ship. Thus through a misunderstanding on both sides the situation was made acute. Lambert moreover, was misled by the fact that the Myowun had brought a body of troops to Rangoon with him, this was a natural precaution in view of the diplomatic situation and did not indicate any desire to commence hostilities. Thinking the Burmese intent on war, Lambert forthwith proclaimed a blockade of the “rivers of Rangoon, the Bassein and the Salween above Maulmain” and ordered all British subjects in Rangoon to embark and all British ships to drop below the Hastings. The British inhabitants were embarked by the boats of the squadron under cover of the Proserpine, the Hermes was employed in towing the merchant vessels away and also, more remarkably, in towing away the King’s ship, which the late Myowun had caused to be armed. The Fox and the other warships now anchored below the Hastings. The next day the Dalla Myowun came to Lambert’s frigate with a view to securing the restoration of the King’s ship, but this was refused and he was told that only an apology by the Myowun in person on the deck of the frigate would be accepted. The following day, the 8th, other officials arrived to seek an accommodation. They bore a letter from the Myowun explaining his refusal to receive any communication through anyone except Edwards on the ground that in the first place he had expected the Commodore to come himself and that in the second place the officers had misbehaved. “Four inferior officers,” he wrote, “an American clergyman named Kincaid and the interpreter Edwards, came in a state of intoxication and contrary to custom, entered the compound on horseback and whilst I was asleep and the Deputy-Governor was waking me, used violent and abusive language. They then went away and conveyed an irritating message to the Commodore and that Officer, listening to their improper and unbecoming representations and with a manifest inclination to implicate the two nations in war, on the 6th of January 1852, at night, with secrecy, took away the ship belonging to His Majesty the King of Ava.” This communication was not likely to improve relations and the Commodore replied by giving the Myowun till 6 p.m. to accept the terms offered, but instead, in the evening a number of war boats went down the river to warn the guard-posts which lay on the river banks and later a message was received that the stockades at the guard-posts would open fire if any ships attempted to move downstream. On the 9th morning the Proserpine and the Phlegethon, which had now joined the squadron together with H.M.S. Serpent, convoyed a number of merchantmen out to sea, the Proserpine then to go to Moulmein and thence to Calcutta to report. The Phlegethon on her return stated that the stockades were fully manned. Next day, the 10th January, the Hermes took the Fox in tow and brought her down as far as the Danot guard-post, while the Phlegethon remained at the Hastings to guard the King’s ship and the merchantmen which were still there. The Hermes returned to the Hastings to bring the King’s ship down and when she arrived off the guard-post with the ship in tow, the battery there opened fire. The Fox and Hermes replied, the Phlegethon came down and also opened fire and within a short time the battery was silenced. A landing party then destroyed the war boats moored off the stockade and spiked the guns of the battery and threw them into the water. A battery which commenced firing from the old Chokey on the other bank of the river, near Thilawa, was also soon silenced. The Fox dropped down to the mouth of the river where the Serpent already lay and on the following morning the rest of the squadron, together with the King’s ship joined them. Two days later Lambert sailed in the Hermes for Calcutta to obtain further instructions from the Governor-General. It is significant that the Burmese stockades had not opened fire until the Hermes came down with the King’s ship in tow. It may also be noted that the Commodore had had explicit instructions from the Governor-General “that no act of hostility is to be committed at present, though the reply of the Governor should be unfavourable, nor until definite instructions regarding such hostilities shall be given by the Government of India.” Before Lambert’s departure news had arrived which showed that the Burmese Government had no desire of war, on Monday the 11th a communication was received from the Myowun promising everything that had been demanded if the King’s ship was returned. But the Commodore realised that the situation had passed beyond his authority. Indeed, war had now become almost inevitable. It is plain that the business had been mishandled. Lambert had from the start been influenced by the complaints of the local merchants, whose views could hardly be unbiased and he had seen insults where none were intended, while his action in seizing the King’s ship is open to the gravest criticism. While the Myowun cannot be acquitted of an excessive regard for his own dignity, it remains that Lambert was too hot-headed a man to be in charge of delicate negotiations. As John Lawrence remarked, “Why did you send a Commodore to Burma if you wanted peace?” and Dalhousie himself, on hearing of Lambert’s proceedings, regretfully admitted that “these Commodores are too combustible for negotiations.” Furthermore, it was the opinion of some Europeans at the time that Capt. Latter, on whose knowledge of the Burmese language the Commodore and his officers were primarily dependent, did his utmost to prejudice relations with the Myowun in the deliberate hope of so provoking a war in which he might find “an opening for his inordinate ambition.” Lord Dalhousie, however, would probably have preferred to avoid war and he sent a further letter to the Myowun offering to settle the matter on payment of the monetary compensation required for Sheppard and Lewis, plus the apology for the treatment received by Fishbourne, together with the re-establishment of the Residency. If these terms were accepted, the blockade would be lifted and the King’s ship would be restored. Lambert, bearing these terms, arrived off the river on the 26th January. On the 31st the Fox went up the river towed by the Company’s steamer Fire Queen to deliver the Governor-General’s message and as she passed the stockade at Manoel de Silva Point the battery there opened fire, the Fox returned the fire but did not stop her passage. She anchored in the evening at the Hastings. When the Fire Queen went down the river next morning she was again fired on and the Tenasserim which steamed upstream to join the Commodore was also fired at. That morning, the 1st February, Lt. Spratt went ashore to deliver the letters embodying the Governor-General’s terms and also to make a protest against the firing by the stockades. The letters were delivered at the main wharf. On the 2nd a reply was received from the Myowun complaining of the removal of the King’s ship as being contrary to custom of all nations, offering to leave the settlement of the compensation till the arrival of the Resident, but, in regard to the apology required, suggesting that “it should be borne in mind that the English Officers have been stating their own version of the case and consequently, whilst shielding themselves, they have thrown all the blame on the other side.” It was further stated, in reply to the protest about firing by the stockades, that on the first occasion it had been justified by the removal of the King’s ship and that on the second occasion it was due to Lambert’s having come up the river without the customary permission. In the evening after the receipt of this reply, the Fox was towed back down the river by the Tenasserim and on this occasion no conflict with the stockades ensued. The blockade was maintained pending further orders from Bengal and on the 18th February the Governor-General sent a communication stating explicitly that war would be declared unless the demands previously made, together with an increased indemnity to meet the expense incurred by maintaining the blockade and preparing for war, were acceded to. The message was an ultimatum, threatening war unless the demands were complied with by the 1st April. War was now inevitable and both sides made active preparations. In Rangoon the last remnants of the old town was swept away. It was at the time complained that “all the houses of the merchants had been sacked and that many of them had been burnt to the ground,” but this measure was undertaken for military reasons, so that no shelter might be left for any invading force between the river and the new town. For this reason the old town, such as still existed, was razed to the ground. Thus the final destruction of Alaungpaya’s Rangoon took place and nothing was now left of the town that had been founded nearly a hundred years before. At the new town energetic measures were taken to strengthen the defences. A force said to number of thirty thousand, but more probably numbering only about ten thousand, was assembled and information received in Bengal from Charles Malcolm Crisp showed that guns were being mounted at the Pagoda and that the stockade was being strengthened. At each of the south, west and east entrances to the Pagoda eight guns were placed, though only one was put at the northern entrance where attack was not to be anticipated. Three of these guns were eighteen-pounders and the rest were six to twelve pounders. At the Myowun’s residence twelve small guns and two twenty-four pounders were placed. A wall was erected along the south face of the Pagoda with embrasures for cannon. The stockade around the new town which had not so far been carried beyond the erection of the bund and of the gateways, was now completed so that it presented a formidable obstacle to an enemy. There was “a row of upright timber extending for miles, as they do round the entire place, except in parts of the north and east sides, each timber fit so be the mainmast of a ship, these timbers three deep and so close to each other that a walking-stick could not be passed between them, behind these upright timbers is a row of horizontal ones, laid one above another and behind all is a bank of earth twenty-four feet broad at the top and forty-five feet at the base, the height of the top of the uprights, from the bottom of the ditch in which they are deeply planted, is generally fourteen feet. The upper part of the of the ditch and that nearest the stockade, is filled with a most formidable abattis in the shape of the pointed branches of trees, stuck firmly into the earth and pointing outwards, beyond this is a deep part of the ditch, which, in the rains, is of course filled with water. The upright timbers are strengthened with connecting planks, the ends of which are inserted on their tops, the other end of the plank being similarly secured by strong wooden pins in the bank itself. They are of such enormous, massive thickness, that firing at the face of a stockade would be a throwing away of powder.” In addition, the King’s Wharf was stockaded, a roof being placed over the stockade in the form of a tank of water to extinguish any shells that might fall on it and a stockade was erected at the old Main Wharf and another at the eastern extremity of the old town. Stockades were also placed along the roads leading from the river to the new town and some of the Pagodas along these roads were fortified. Rangoon was not on this occasion to be taken by surprise. On the other side, preparations were made which, it was hoped, would obviate the disastrous mismanagement of 1824. Medical equipment, fresh meat and other stores, were provided in plenty, timber, mats etc. for the construction of temporary barracks were prepared by Chinese carpenters at Moulmein to be taken to Rangoon in due course, hospitals were made ready at Amherst and sufficient steamship accommodation for the transport thither of sick or wounded was provided. A careful check was placed on the supply of spirits to the troops. A force of nearly 6,000 men, with thirty-five pieces of artillery, escorted by fifteen warships and carried in fifteen steamers, was organised under the command of Lt.-General Henry Godwin, who had served in the war of 1824, this force was drawn from both Bengal and Madras. The naval force was under the command of Rear-Admiral Charles Austen, (brother of the novelist Jane Austin.) The naval Commander-in-Chief arrived off the mouth of the river on the 1st April and the Bengal detachment on the 2nd. Madras Infantry Brigade Bengal Infantry Brigade H.M. 51st Regt. H.M. 18th Regt. 5th Madras N.I. H.M. 80th Regt. 9th Madras N.I. 40th Bengal N.I. 35th Madras N.I. 3 Companies Royal Artillery – 3 Companies Madras Artillery - 2 Companies Madras Sapper & Miners. The Proserpine was then sent up to Rangoon under a flag of truce with Capt. Lutter to enquire whether any reply had been received to the ultimatum, but the ship was fired on from the stockades and returned fire. Any hope of peace being now at an end, the expeditionary force did not, nevertheless, commence an attack, as the Madras Division had not yet arrived, a detachment was sent instead against Martaban and meanwhile Commodore Lambert and the Fox with Serpent, Tenasserim and Phlegethon and three companies of H.M.’s 80th Royal Irish, went up the river on the 4th afternoon. On the morning of the 5th the Serpent and the Phlegethon with one company of the 18th made an attack on the Manoel de Silva stockade which was taken and destroyed while the Fox and Tenasserim attached the Danot guard-post, which, as also the stockade at the old Chokey on the other bank, was likewise taken and burnt. The demolition of these defences cleared the way for an advance up the river. On the 10th the Madras division having arrived three days earlier, the expedition went up to the Hastings. The next day, Easter Sunday, as soon as the tide served, the ships crossed the bar and took up their positions off the old town. When the first ship anchored, firing began from the stockades on both sides of the river, to which the warships replied and after about an hour the battery of nine eighteen-pounder guns at the King’s Wharf blew up, the gunpowder, kept in a row of large jars, having caught fire. A party of seamen and marines with a company of the 18th was landed on the Dalla side and under cover of the ship’s guns took the three stockades there and burnt them, while the Serpent and Phlegethon proceeded up the river and anchored off Kemmendine to capture the war-boats kept there and prevent any fire-rafts from coming down. No attempt was made that day to effect a landing on the Rangoon bank, effort being directed to clearing the ground by gunfire, to such effect that the three stockades along the waterside were completely destroyed. At 4 a.m. the following day, the 12th, the troops commenced to disembark. The guns of the ships covered this and kept up a heavy bombardment of the new town which towards evening blew up a magazine near the Pagoda and set fire to the stockade in several places. The troops meanwhile advanced not along the roads leading from the waterside to the Pagoda, but by a route to the east of the old town. The advance was impeded by the creeks, the bridges over which had been destroyed by the defending army and temporary bridges had to be constructed by the Sappers. The cannonade of the defenders from the Pagoda Hill was a still more serious obstacle and equally gunfire from the Theinbyu or “White House Stockade.” Burmese skirmishers in the neighbourhood of the Stockade were easily driven off but it proved impossible to advance until the guns behind the defences had been silenced. Four guns which accompanied the attacking force expending all their ammunition with little effect and not until two twenty-four pounder howitzers had been brought up was it possible to storm the Stockade, this was done, with some loss, by eleven o’clock. The exertions so far required and the heat, led the commander to suspend the advance for that day and the troops therefore camped near the Theinbyu till next morning but the bombardment from the ships still continued throughout the night and did much destruction to the new town. On the 13th it as found that the heavy guns had not yet been brought ashore and that rations had not been prepared for an advance. No movement was made therefore till next day when the advance was resumed along the route to the east of the town. The defenders had anticipated that the advance would be made along the old roads leading to the southern face of the new town’s stockade and while those roads had been prepared for defence, the route actually chosen was not so well provided for, the attack was thus able to proceed on the 14th morning, through the jungle from the Theinbyu, between Kandawgale and the Kandawgyi, until checked by the guns of the Pagoda. The infantry having cleared the ground of skirmishers, the heavy guns were now brought up by the artillerymen and the naval brigade to a point near the south-west of the Kandawgyi, though some loss was suffered from the marksmanship of the guns at the Pagoda and on the high ground above the position now occupied. It had been intended by General Godwin to storm the stockade on the east side at noon, but at eleven o’clock Capt. Lutter reported to him that C.M. Crisp who had previously sent information about the defences of Rangoon, had told him that the attack would be better directed at the Pagoda, the east entrance of which was very inadequately defended, rather than the stockade itself. A storming party therefore advanced over a distance of eight hundred yards through open country under a heavy fire, rushed up the steps and entered the Pagoda platform. The position being now untenable the Burmese had no option but to retire, making their way out by the southern and western gates of the town under a heavy fire from the warships. So Rangoon was taken in a manner which reflects nothing but credit on the courage of both attackers and defenders. There was some further skirmishes around Rangoon but little serious fighting. The rest of the Delta was quickly occupied and in default of the execution of a treaty with the Burmese Government, as declared annexed by a proclamation dated the 20th December 1852. |

|

It may be noted that whereas in 1824 the town and Pagoda had been taken without loss of a man,

in 1852 the attacking force lost sixteen killed and one hundred and thirty-three wounded, besides some thirty of the naval force. In addition, the army lost two officers by sun-stroke, Major H. Griffiths, Brigade Major, Madras Brigade. and Major A.F. Oakes, Madras Artillery, whose death is commemorated by an obelisque on the Prome Road although he was actually buried at the Botataung Pagoda. |

After the taking of the town, the occupying force was distributed either under canvas or among the larger buildings, generally kyaungs in Tharawaddy’s city, though the artillery, as in 1824 was stationed on the Pagoda Hill.....

Thanks to the careful preparations made under the direction of the Governor-General, the garrison which held Rangoon during the rains of 1852 suffered few of the discomforts which had afflicted their predecessors of 1824. ... and there was very little sickness. An outbreak of cholera which occurred a few days after the occupation, mainly as a result of an excessive consumption of pineapples and a certain amount of dysentery were the principal causes of casualties...

The troops, as in 1824, found little in the way of loot in the town, but plenty in the pagodas. “Numbers of curious sawmies, of crass, of clay covered with a thin coating of silver, wood and alabaster, are being brought into camp by the men. Gilt wooden cabinets and boxes, some of them very chaste, are likewise to be seen here and there,” wrote one observer on the 18th April and, a few days later, “It is strange to observe the numerous idols lying about the upper terrace. There is a soldier busy with his pick-axe, excavating a huge golden image with as much coolness as if he were digging a trench. He is looking for treasure – gold, or small silver figures, or rubies, which he will dispose of as well as he can.”...

Steps were also taken to facilitate navigation by laying down buoys, employing a pilot-brig and constructing a new wharf; and to meet the expenditure so incurred a tonnage-duty of four annas a ton was imposed on all ships not in the employ of Government arriving in the port after the 22nd May: R.S. Edwards being appointed Collector for the purpose.

For the time being, the town remained under military administration, Capt. Latter, and later Lt. R.D. Ardagh, acting as magistrates.

When the annexation for the Delta, now to be the commissioner’s division of Pegu, was determined on, provision needed to be made for the civil government. As early as the month of May 1852, only a few weeks after the occupation of Rangoon, certain of the European inhabitants who had now returned had petitioned Genl. Godwin for the appointment of a civil magistrate and had indicated as a suitable candidate for the post the turbulent May Flower Crisp, who had himself organised the petition. A copy of the petition was sent direct to the Governor-General, from whom it received short shrift; for the firm of Crisp & Co., which had so often been in hot water with the Burmese authorities, was equally in the bad books of Lord Dalhousie, since it had “sold powder, muskets and military stores” to the Burmese after it had become quite apparent that hostilities were about to occur. It is curious that Crisp’s son, C.M. Crisp, should also have provided information to the Governor General about the fortifications of Rangoon and should at the time of the attack on the Pagoda have shown the way to the eastern entrance by which the attackers took, with little loss, what would otherwise have been a very strong position: but the Myowun’s refusal to pay for the arms no doubt accounts for this. Lord Dalhousie rejected the petition and sent a plain warning that Crisp was to abstain from all interference with the people of the Pegu province on pain of deportation: from this it would appear that Crisp had already been trying to exercise some sort of authority in the town. Capt. Phayre, Commissioner of Arakan, appears to have been more favourably disposed towards the petition, however, writing to Crisp that he had “great claims from your long residence among (the inhabitants of Rangoon) and your intimate knowledge of their claims, interests and wants.”

... A Deputy Commissioner, in the person of Capt. T.P. Sparks, was also appointed for the Rangoon town and district...

Capt. Phayre arrived in the Rangoon river on the 18th December and landed on the morning of the 19th. On the morning of the 1st the troops were paraded at 6 a.m. outside the stockade and the proclamation of annexation was read. In this way the civil government of Rangoon was inaugurated.

... The question also arose whether a lighthouse should be erected at the river mouth. Phayre proposed to station a lightship there..... The King’s ship which the Commodore had seized in January 1852 could be thus utilised.

A post-office system was inaugurated: the first Postmaster was C.M. Crisp, who received the appointment as a reward for his assistance at the storming of the Pagoda. The crimes of Messrs. Crisp & Co. were evidently soon forgiven.

... The Prize Agents had been partially responsible for what was, in the eyes of men like Dalhousie and Phayre, an even graver impropriety. As in 1824, the troops had sought for loot and the Pagodas of Rangoon and of the other parts of the Delta had suffered. In the case of the more important pagodas it would seem that the Prize Agents were responsible, in other cases many of the military and naval officers were personally responsible.

Phayre on his arrival in Rangoon found that once more even the Shwe Dagon had not been exempt from attack, the officer responsible for riving a gallery into the Pagoda, Major Fraser, R.E. advancing, however, the ingenious excuse that he wanted to see whether the pagoda could be used as a powder-magazine, though unkind critics opined that King Hsinbyshin’s treasure was more in his mind. Phayre addressed Brigadier Sir John Cheape, who was in command at Rangoon, pointing out the objectionable nature of such a proceeding which had, he was informed, caused great pain to King Mindon and might thus lead to a further breach of friendship..... “The Most Noble the Governor-General in Council has learnt with regret and dissatisfaction the continued destruction and injury to Pagodas and places of worship throughout the Province of Pegu. Such acts of violence in a time of war cannot be wholly prevented, but his Lordship in Council feels strongly the scandal which their continuance now is calculated to bring upon our national character and the exasperation which an open and almost universal desecration of their sacred places may produce in the minds of the people of Pegu. His Lordship in Council therefore desires to notify to all who are in the service of Government that whoever shall be proved to offend in this particular hereafter shall be punished with prompt severity. The Governor-General in Council expects that all officers within the Province, whether Civil or Military, will give special attention to the execution of the orders which are notified hereby.”

Thanks to the careful preparations made under the direction of the Governor-General, the garrison which held Rangoon during the rains of 1852 suffered few of the discomforts which had afflicted their predecessors of 1824. ... and there was very little sickness. An outbreak of cholera which occurred a few days after the occupation, mainly as a result of an excessive consumption of pineapples and a certain amount of dysentery were the principal causes of casualties...

The troops, as in 1824, found little in the way of loot in the town, but plenty in the pagodas. “Numbers of curious sawmies, of crass, of clay covered with a thin coating of silver, wood and alabaster, are being brought into camp by the men. Gilt wooden cabinets and boxes, some of them very chaste, are likewise to be seen here and there,” wrote one observer on the 18th April and, a few days later, “It is strange to observe the numerous idols lying about the upper terrace. There is a soldier busy with his pick-axe, excavating a huge golden image with as much coolness as if he were digging a trench. He is looking for treasure – gold, or small silver figures, or rubies, which he will dispose of as well as he can.”...

Steps were also taken to facilitate navigation by laying down buoys, employing a pilot-brig and constructing a new wharf; and to meet the expenditure so incurred a tonnage-duty of four annas a ton was imposed on all ships not in the employ of Government arriving in the port after the 22nd May: R.S. Edwards being appointed Collector for the purpose.

For the time being, the town remained under military administration, Capt. Latter, and later Lt. R.D. Ardagh, acting as magistrates.

When the annexation for the Delta, now to be the commissioner’s division of Pegu, was determined on, provision needed to be made for the civil government. As early as the month of May 1852, only a few weeks after the occupation of Rangoon, certain of the European inhabitants who had now returned had petitioned Genl. Godwin for the appointment of a civil magistrate and had indicated as a suitable candidate for the post the turbulent May Flower Crisp, who had himself organised the petition. A copy of the petition was sent direct to the Governor-General, from whom it received short shrift; for the firm of Crisp & Co., which had so often been in hot water with the Burmese authorities, was equally in the bad books of Lord Dalhousie, since it had “sold powder, muskets and military stores” to the Burmese after it had become quite apparent that hostilities were about to occur. It is curious that Crisp’s son, C.M. Crisp, should also have provided information to the Governor General about the fortifications of Rangoon and should at the time of the attack on the Pagoda have shown the way to the eastern entrance by which the attackers took, with little loss, what would otherwise have been a very strong position: but the Myowun’s refusal to pay for the arms no doubt accounts for this. Lord Dalhousie rejected the petition and sent a plain warning that Crisp was to abstain from all interference with the people of the Pegu province on pain of deportation: from this it would appear that Crisp had already been trying to exercise some sort of authority in the town. Capt. Phayre, Commissioner of Arakan, appears to have been more favourably disposed towards the petition, however, writing to Crisp that he had “great claims from your long residence among (the inhabitants of Rangoon) and your intimate knowledge of their claims, interests and wants.”

... A Deputy Commissioner, in the person of Capt. T.P. Sparks, was also appointed for the Rangoon town and district...

Capt. Phayre arrived in the Rangoon river on the 18th December and landed on the morning of the 19th. On the morning of the 1st the troops were paraded at 6 a.m. outside the stockade and the proclamation of annexation was read. In this way the civil government of Rangoon was inaugurated.

... The question also arose whether a lighthouse should be erected at the river mouth. Phayre proposed to station a lightship there..... The King’s ship which the Commodore had seized in January 1852 could be thus utilised.

A post-office system was inaugurated: the first Postmaster was C.M. Crisp, who received the appointment as a reward for his assistance at the storming of the Pagoda. The crimes of Messrs. Crisp & Co. were evidently soon forgiven.

... The Prize Agents had been partially responsible for what was, in the eyes of men like Dalhousie and Phayre, an even graver impropriety. As in 1824, the troops had sought for loot and the Pagodas of Rangoon and of the other parts of the Delta had suffered. In the case of the more important pagodas it would seem that the Prize Agents were responsible, in other cases many of the military and naval officers were personally responsible.

Phayre on his arrival in Rangoon found that once more even the Shwe Dagon had not been exempt from attack, the officer responsible for riving a gallery into the Pagoda, Major Fraser, R.E. advancing, however, the ingenious excuse that he wanted to see whether the pagoda could be used as a powder-magazine, though unkind critics opined that King Hsinbyshin’s treasure was more in his mind. Phayre addressed Brigadier Sir John Cheape, who was in command at Rangoon, pointing out the objectionable nature of such a proceeding which had, he was informed, caused great pain to King Mindon and might thus lead to a further breach of friendship..... “The Most Noble the Governor-General in Council has learnt with regret and dissatisfaction the continued destruction and injury to Pagodas and places of worship throughout the Province of Pegu. Such acts of violence in a time of war cannot be wholly prevented, but his Lordship in Council feels strongly the scandal which their continuance now is calculated to bring upon our national character and the exasperation which an open and almost universal desecration of their sacred places may produce in the minds of the people of Pegu. His Lordship in Council therefore desires to notify to all who are in the service of Government that whoever shall be proved to offend in this particular hereafter shall be punished with prompt severity. The Governor-General in Council expects that all officers within the Province, whether Civil or Military, will give special attention to the execution of the orders which are notified hereby.”

Additional information "Narrative of the Operations at Rangoon 1852" by By Lt. William F.B. Laurie, Madras Artillery, which also contains a brief appendix on the 1st A.-B war, digitised by Google Books can be found here