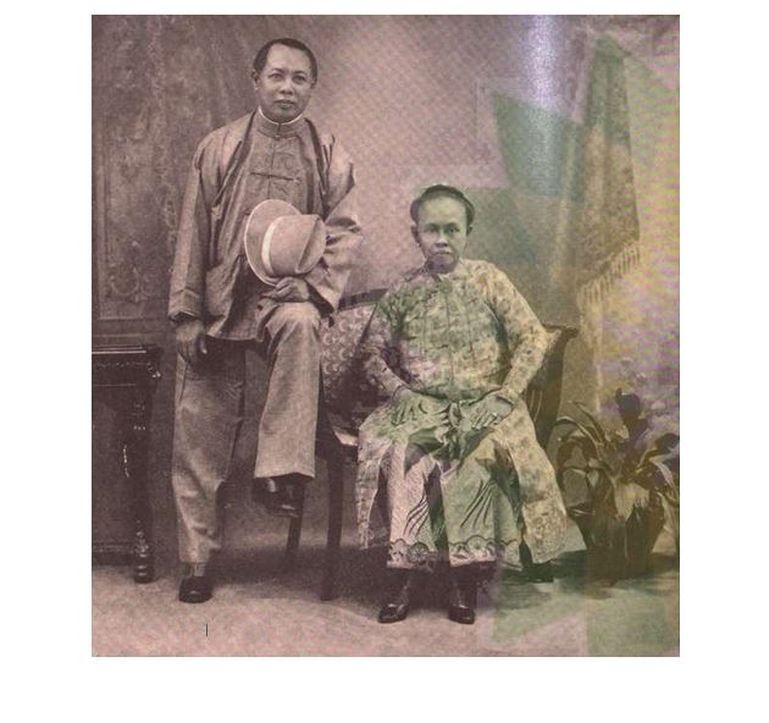

Lim Chin Tsong

Copyright – BP Archives, “The Bull Wheel” magazine

Reproduced by the Anglo-Burmese Library 2011 by kind permission

|

There have always been Chinese in Burma and there always will be. In the early 1900’s when the Burmah Oil Company was all set for expansion in production, refining and marketing, there were several thousand of them in Rangoon and on one of them, Lim Chin Tsong, a Chinese merchant of Singapore origin, the company in 1908 bestowed the responsibility for the marketing of its products throughout the country. For the best part of the next 12 years the mere mention of the name Lim Chin Tsong was enough to send a shudder through the company – not only in Rangoon but also in Glasgow, where the directors sat.

The Hon’ble Mr. Lim Chin Tsong, O.B.E., Member of the Legislative Council of Burma, owner of steamers, patron of the arts, rubber planter, tin miner and possessor of a dozen other irons in different fires, was a man of remarkable character, great personality and endearing charm. As agent for the Burmah Oil Company he pushed products sales vigorously and successfully through sub-agencies up and down the country. Everyone knew him; most people liked him. His only fault, so far as the company was concerned, was that his business methods, or rather the lack of them, drove the company’s accountants up the proverbial wall. For Lim Chin Tsong (shortened in company correspondence to L.C.T., so often did his name have cause to appear) ran up large outstandings with his oil agency business, and in their attempts to find out the true state of his financial affairs, the accountants were up against the difficulty that his books were kept in Chinese. L.C.T. could speak the language, but could neither read nor write it, and the staid Scots accountants, brought up to believe that it was almost better to be dead than in debt, were seldom able to make head or tail of his entries without the aid of an interpreter. The interpreter usually turned out to be Chin Tsong's head-clerk: he did the job well enough but unfortunately most of the mysteries remained because all the transactions - not only those relating to kerosine, candle and lube oil sales but all the others too - were jumbled together in one general chaos. Eventually, after a year or two of unscrambling, it became all too dear that a sizeable trade gap existed between agent and company, the sales proceeds being far less than the value of the goods supplied. Again and again L.C.T. fell seriously behind with his payments, and the company was forever coming down on him. The accountants dinged him. The directors chased him. The Chairman, John T. Cargill, pleaded with him personally and by letter. Finlay Fleming & Co., the Burmah's managing agents in those early days, repeatedly read the riot act to him. To all these tweaks of the celestial pigtail the inscrutable Lim Chin Tsong gave a polite, apologetic and usually evasive response. He was very sorry and would pay up next week. It was the Chinese New Year and payments due from sub-agents were slow coming in, the whole of the Chinese community being out on the tiles. It was the Full Moon of Kason, a big Burmese festival, so there might be a little delay owing to the holiday. He would send the money round as soon as he could get to the bank. Meanwhile, festival or no festival, the abacuses in L.C.T.'s shop in China Street, Rangoon, clicked merrily away and the books continued to be entered up in Chinese characters despite the company's strict orders that they be translated into English. Lim Chin Tsong, son of Lim Soo Hean, was born in 1870, six years before the foundations of the first Burmah Oil Company were laid. By 1886 the father was already in the oil marketing business, and young Lim Chin Tsong was helping out. Two years later Lim Soo Hean died, and L.C.T. inherited the business. At first he sold B.O.C. kerosine on behalf of Cheng Taik, a distant relative who claimed to have been given the agency by Finlay Fleming & Co. (though L.C.T. was able to prove later that Cheng Taik was merely a commission agent) and to whom he handed over two-and-a-half per cent on sales. Candles, however, Chin Tsong sold on his own account, dealing direct as - his father had done with the Burmah Oil Company. In I908 the company closed its account with Cheng Taik and gave the sole agency for Burmah Oil's product sales to L.C.T., who was then 38. Chin Tsong established sub-agents and branches - all Chinese run - all over the country, operating from Rangoon under the name Lim Soo Hean & Co. (telegraphic address: “CHIPPYCHOP”). Prior to 1908 the company's production of crude was shipped down the Irrawaddy from the northern oilfields in river flats and barges, but in that year the B.O.C. completed a 300-mile-long pipeline linking the fields with the refining centre at Syriam, a little south of Rangoon. This permitted a considerable increase in throughput, and consequently in the volume of products available for the market, local and export. By 1910 production had risen to over half-a-million tons (compared with the 60,000 Ions of 1899 and the trickle of 10,000 tons in 1889) and much of the total was going across the Bay of Bengal in B.O.C. tankers to India proper, where the agency was safely and properly administered by Shaw Wallace and Company Ltd. Burmah Oil could dearly have wished that a similar set-up to S.W. and Co. existed in Burma, for within a few years of starting the agency Lim Chin Tsong was behind with his payments and the company had begun to put the pressure on to recover the amounts due. The outstandings were certainly large enough to cause the company anxiety - in January 1911 they ran into six figures sterling. The situation got so bad that the directors instructed their Rangoon office to wire them a weekly statement of the position. Rangoon had to say what was being done about things too. And as the months went by the battle went on, ebbing or flowing as L.C.T. was in or out of funds. The company's chief representative in Burma in the early days of the fight was Campbell Kirkman Finlay, senior partner in Finlay Fleming & Co., burra sahib in Rangoon from 1908 to 1912 and later a director of the Burmah Oil Company. A widely read and travelled man, he was endowed with a great sense of humour, was fond of the ordinary Burman, and took a particularly keen interest in geology. With Lim Chin Tsong, however, he was unable to get very far. He wrote to him frequently and sometimes in very strong terms, but he was never discourteous to him and almost always ended his letters to the Chinaman "with plenty salaams". When Kirkman Finlay's knighthood was announced in 1912, the year he returned to England, L.C.T. sent him a (translated) letter of congratulations saying: "I can assure you I shall miss the genial smile with which you have always greeted me whenever I had the pleasure of seeing you". Kirkman Finlay's tireless efforts to get Chin Tsong to pay his debts had the backing of Mr. John T. Cargill, the chairman, at home - but only up to a point. Kirkman Finlay was all for taking the agency away from L.C.T. and running it with the company's staff, but Cargill thought this was too drastic a step to take; anyway the staff didn't exist, at least not in Burma, and with the war approaching it would have been difficult to recruit suitable men at home and get them out to the East. Finally, in the cold weather of 1912-13, Cargill himself went out and had a long and serious talk with L.C.T. about his indebtedness to the company. Chin Tsong had anticipated the visit, and had earlier written to the chairman saying: "I will see you when you visit Burma. You may rest assured that the arrangements to keep the outstanding balance against me down will not be exceeded. Looking forward to the pleasure of seeing you and with my salaams to Lady Cargill and yourself, yours apologetically, Lim Chin Tsong". (The reference to Lady Cargill was a premature touch of Oriental courtesy: Cargill was not created a baronet until 1920). Alas, the confrontation had little effect. L.C.T. promised to pay to the B.O.C. daily all the money received against sales, but as soon as Cargill had left Burma for Ceylon and the U.K. the debit balance crept up. Rangoon's next weekly letter to Glasgow was short and to the point: "The string is tightening around L.C.T.'s neck. The only response this week was a promise of Rs. 80.000 and some complimentary tickets to the St. Leger grandstand!" By this time Chin Tsong was in financial difficulties also with his other enterprises, and it was generally believed that he was using the monies that were rightly due to the company to stave off his other creditors. Burmah Oil had now placed a limit on the extent to which he could run up debts, and beyond this he was told not to go. As security for this overdraft the company took first or second call on L.C.T.'s ships, rubber estates, match factory and landed property - all of which, and more later, were mortgaged in favour of the B.O.C. By 1914 there were indeed so many different liens that they became known as the omnibus mortgage. The battle continued. One week Chin Tsong would be desperately hard pressed, with the ominous word bankruptcy ringing in his ears; the next he would strike it rich with a big steamer freight - or the promise of one. On several occasions he was, said Rangoon, "at the end of his tether, shedding copious tears;" at other times he was in the millionaire bracket, entertaining lavishly at the Rangoon race track. When he was broke the directors refused to treat him harshly; when he was flush they went for him again. The company was always trying to find ways to help him, even to the extent of advising him about his income tax returns, his property dealings, and his match factory, the products of which so delighted the Viceroy of India, Lord Chelmsford, that he prohibited the use of any other make at Government House. "I always use them", said Adam Ritchie, of Finlay Fleming & Co., and so does the Governor". When his eldest son was married the whole of the European and Eurasian population of Rangoon was present at the ceremony, which took place at Chin Tsong’s newly-built palace on the Kokine Road. The Burmese came on the second day, the Moslems on the third and the Chinese on the last. The Rangoon office commented darkly: "L.C.T. apparently has no intention of discussing his financial situation until this affair is over - and probably not even then". The three main charges that the Rangoon accountants levelled at him were that he was incompetent, never knowing at any time how much money he owed and to whom: unbusinesslike, in that he extended everlasting credit; and foolish because he was a profligate gambler. In the same breath, however, they admitted that he was not by any means a knave. In the higher echelons of Burma's civic, business and social life he had very good connections, and among his own people he was known for his kindness and generosity; part of the commission that his sub-agents received on sales was paid into a fund to help maintain schools for Chinese children. Up and down the country he nevertheless had the reputation of being a spend-thrift to whom money was a case of easy come, easy go. But in Chin Tsong's hands the more it came, the faster it went, and what really riled the accountants was that they couldn't get their hands on it when it was coming. They remonstrated all the time, but they had to be careful not to overdo their admonishments for Chin Tsong was more than the sole agent for the company; he had played a prominent part in securing for the company the right to obtain crude oil from certain native well-owners and producers In Upper Burma, and without his help in this direction the B O.C's early future might have been different. Naturally he was rewarded for this success, being paid a commission of so many annas on every barrel of oil produced. Raising the wind proved easier for L.C.T. during the war. In 1915 he won an action over the cancellation of a steamer charter, and with part of money bought a Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost, which he had shipped out from England. A year later he was noted by the company's staff in Rangoon to have gone up country to Maymyo, the hot-weather seat of the government, where he was said to be "hunting an honour". This in due course he received, for he gave a large sum of money to the war fund. He sent his sons to be educated in England, and said that the himself would go one day - which he did, but not until the agency had been taken away from him and put into the hands of the company. For the time came when the directors, sentimentally inclined to L.C.T. as they were, could no longer play the waiting game. The market was expanding at the rate of 14 percent per annum; further expansions, both in Burma and Assam, were envisaged; and the end of the war meant that company staff would soon be available to take over the business and run it on proper lines. Chin Tsong moved heaven and earth to try and find the money due to the company and at one stage had almost cleared off his debts, though not the interest on the overdraft. Under the spell of Chin Tsong's personality the Rangoon office was inclined to take a lenient view of his request to be released from the interest payments due to the company on his outstandings, but in Glasgow the directors demurred and the screws were gently applied to the Chinaman again. In 1919 the crunch came. Lim Chin Tsong's agency was at last about to be cancelled, and preparations were made for the Burma Agency department to take over. "It will not bring him down", said Rangoon, "as he is far from insolvent. His trouble is that he hasn't got the ready money. We gave him the option of either taking notice from us or his giving us notice. He chose the latter. He tried to look pleased and promised every assistance, and we promised him all help to get in all his outstandings". In September the same year, Lim Chin Tsong, ready money or not, achieved his ambition to go to the U.K. He filled one of his steamers, the Seang Bee (formerly S.S. Shropshire Bibby Line), with his family, his relations and his friends and set sail for London on 20th September, 1919, returning to Burma on 23rd January 1920. He had the time of his life there, met Cargill in London, went up to Scotland, and spent £30,000 at Harrods on furnishings for his Rangoon palace and in amusing himself in the West End. When he got hack he disappeared for a time, and when he eventually showed up in Rangoon early in February he told the B.O.C. he hoped to have accumulated enough money from the freight carried by the Seang Bee to pay the whole of his outstandings with the company. These hopes were not fulfilled. Instead he used the freight earnings to launch out in other directions. His residence, by this time, was truly palatial by oriental standards, and in it he and Mrs Chin Tsong (Tan Guat Tean, to give her Chinese name) acted as delightful hosts amid luxurious surroundings. Distinguished visitors were entertained to tea at which, if they had a taste for the exotic, dainty sandwiches of seaweed jelly from China were served, and then conducted from room to room to see the ornamental treasures, valuable draperies, costly rugs and bed trimmings and elaborately-carved chests crammed with gorgeous silken garments. In 1922 L.C.T. was again on the verge of bankruptcy. A year later he was evading arrest, refusing to answer the door to callers at his palace, which the local newspapers described as "one of the show places of Burma". He had not been to his shop in China Street for months. He was, in fact, in hiding. An application in the High Court of Burma asking that he be judged insolvent was adjourned for a week while renewed attempts were made to execute the warrant. But in the mean¬time, early on 2nd November 1923, Lim Chin Tsong died. Mr. W. A. Gray, then in charge of the Burmah Oil Company's affairs in Rangoon, immediately despatched a letter of sympathy to the widow. Mrs. Lim Chin Tsong replied a few days later: "I thank you very sincerely for your kind message. It was a source of comfort and solace to receive such a letter from you personally and from Burmah Oil at a time when we were all stricken down with sorrow at the sudden and unexpected death of my dear husband, who, for the prime years of his life, was so closely and intimately associated with the Burmah Oil Company, and whose kindness and co-operation he always appreciated. "On behalf of my son and daughter and personally too I convey to you and the company my heartfelt thanks." Being illiterate, she had to have the letter written for her. The death of Lim Chin Tsong, which was due partly to influenza and fever and partly to his distress at a comparatively trivial annoyance - a threat from the telephone company to sever his phone owing to the non-payment of rent - was by no means the end of Lim Soo Hean & Co., of which L.C.T. had been proprietor for 35 years. Lim Kar Chang, his eldest son, carried on the business - and within a week of the funeral was seeking assistance from the Burmah Oil Company in the settlement of his father's personal affairs, though not the debts that were still owing to the company. Whether the latter were eventually paid is not recorded in the archives - the likelihood is that they were written off - and during the next 15 years the legendary name of Chin Tsong gradually faded from the files. Then, in late 1938 it suddenly re-appeared. Mrs Chin Tsong, though still living in the Kokine Road palace, was found to be destitute. As soon as the Rangoon office discovered her plight the directors were told. They promised sympathetic consideration of her case. In January 1939, she received an ex-gratia payment in recognition of the long association that existed between the company and her husband. Mrs Chin Tsong had the company's document translated and explained to her in Chinese by an interpreter, after which she signed the paper with an X. |