Sentry Page Protection

Please Wait...

The Third A-B War - 1885/86

a few of the events which lead up to it...

extracts from A History of Rangoon

by B.R. Pearn, published 1939

a few of the events which lead up to it...

extracts from A History of Rangoon

by B.R. Pearn, published 1939

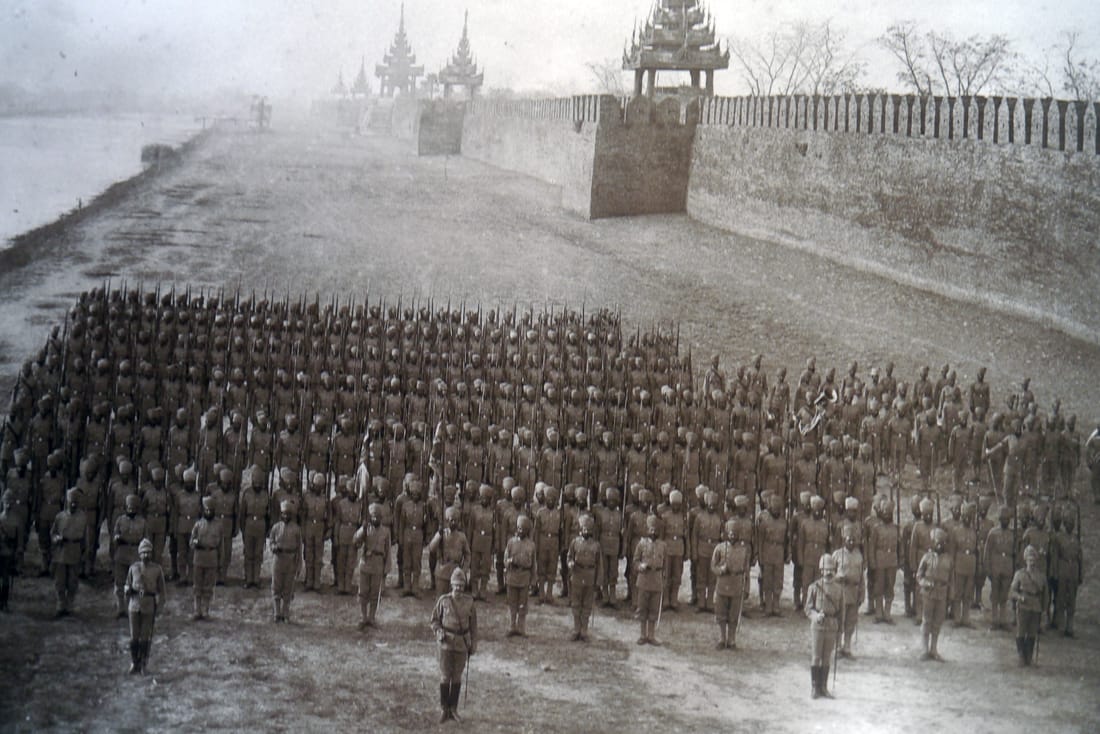

Fort Dufferin (ex Mandalay Palace) 1885

|

.... Rangoon as a commercial centre continued to flourish. Stimulus was given to commerce in this period by the annexation of Upper Burma. The extension of trade and consequently of political control into Upper Burma was no new project. As early as the year 1867, when Col. Fytche had negotiated the commercial treaty that year with King Mindon, the Government of India had suggested the inclusion of an article to the effect that “The Burmese ruler engages not to enter into negotiations or communication of any kind with any foreign power, except with the consent, previously obtained, of the British ruler,” but Fytche was of opinion that any attempt to establish suzerainty would not only fail but would jeopardise the whole of his negotiations and the proposal was therefore dropped. With the deterioration of relations after the accession of King Thibaw, however, the suggestion that political control over Upper Burma should be enforced was revived and the English merchants of Rangoon played a considerable part in an agitation to this end. As early as 1879 the Rangoon Chamber of Commerce drew the attention of the Chief Commissioner to the acute difficulties under which, it was stated, commerce with Upper Burma was labouring and similar representations were made in subsequent years. The Chief Commissioner of the early 1880’s Sir Charles Bernard, was, however, averse to intervention and for the time being his influence prevailed. But in 1884, a public meeting of the inhabitants of Rangoon was convened in the Town Hall at which it was resolved to press upon Government the necessity of annexing Upper Burma. The minutes of this meeting stated that there was present on this occasion “an immense concourse of Burmese, Europeans, Chinese and natives of India,” who unanimously passed the proposal; but a local newspaper, the British Burma News, affirmed that “at this meeting not so many as five persons of position among the Burmese, Chinese or foreign community” were present, apart from the English inhabitants; and according to a report by the Chief Commissioner the Burmese members of the Municipal Committee convened a meeting of their own at which the Burmese elders resolved that they were concerned only with the welfare and prosperity of Lower Burma and that “they could not interfere with foreign affairs.” The Chamber of Commerce, however, supported the resolutions of the public meeting and drew attention to the falling off of trade and to the “increased spirit of lawlessness” in Lower Burma which, it was stated, had occurred since King Thibaw’s accession. At the same time the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company complained that the numerous dacoities in Upper Burma had produced a feeling of insecurity among its employees which could be allayed only if some protection were afforded by Government. Again in 1885 the Chamber of Commerce stated that as a result of the falling off of trade with Upper Burma “ the position of the trading classes in Rangoon daily becomes more hopeless. Failures in the bazaar are almost daily occurrences;... credit is almost at an end and there is no prospect of better times for the mercantile classes until an end had been put to the disorder in Upper Burma.” The imposition of monopolies in Upper Burma, in contravention, it was held, of the commercial treaty of 1867, was also a ground of protest. On the other hand, the chief Commissioner pointed out that the average of trade with Upper Burma from 1880 to 1884 was in fact somewhat greater than in the four years prior to King Thibaw’s accession; and that though in respect to piece goods, which formed the major commodity imported through Rangoon, there had been a decline in the year 1884-85, this was due to the failure of the rice crop in Upper Burma, in consequence of which the export of rice from Lower Burma had increased during the first six months of the year by over twenty-nine lakhs of rupees, while inevitably the power of the people of Upper Burma to purchase other commodities was proportionately reduced. The agitation continued, nevertheless, and Chambers of Commerce in Great Britain were circularised by the Rangoon Chamber with the request, which was acceded to, to bring pressure to bear on the Imperial Government to interfere in the affairs of Upper Burma. Petitions were submitted to the Secretary of State from the Chamber of Commerce of Macclesfield, Glasgow, Manchester, London and Liverpool; and when the threat of French intervention in Upper Burma seemed likely to materialise, the Rangoon Chamber of Commerce again made protests to the Chief Commissioner urging annexation and the London Chamber of Commerce followed this example, as did the Glasgow Chamber, the Liverpool Chamber and even the Salt Chamber of Commerce, Northwich. Private firms also sent in similar petitions. As the Chief Commissioner observed, “for some years back British merchants and other Englishmen in Lower Burma have desired to see Ava annexed and to have a strong homogenous British province stretching from the sea to the confines of China. It has been thought that such annexation would promote trade and also improve the prosperity of the people by securing the exploitation of the coal, teak, earth oil and other valuable products of Ava and by opening a direct route for trade with the western provinces of China.” There can be little doubt that the pressure brought to bear by the Rangoon Chamber of Commerce and its corresponding bodies in Great Britain had a good deal to do with the willingness of the Imperial Government to bring Upper Burma under the British Crown. The out-break of the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885 did not directly affect Rangoon, except in so far as the generally disturbed condition of the country led to an increase of crime and except that the Rangoon Volunteer Rifles, which had now been formed in 1877 under the command of Major Evanson, saw a certain amount of active service. The mounted infantry detachment was sent into the Pegu district to assist in maintaining order and the remainder of the corps preformed guard duties in Rangoon in place of the regular forces. The merchants of Rangoon were by no means disappointed in their hopeful anticipations of increased trade resulting from the annexation of Upper Burma which they had so strenuously demanded. In 1881-82 imports valued at Rs. 505,00,000; at the end of the century their value was Rs. 913,00,000; exports in 1881-82 amounted to Rs. 473,00,000 and at the end of the century their value was Rs. 1354,00,000. Among imports textiles still ranked first, with cotton providing two-thirds of the total of textiles. Among exports, rice still predominated, with timber second, but mineral oil, the export of which had formerly been trivial, ranked third at the end of the century. The effect of the annexation of Upper Burma, which opened the petroleum wells to development, is here clearly perceived; and in general the annexation provided opportunities for commerce on a scale unknown before. The export of rice, which twenty years earlier was a matter of 302 lakhs of rupees, at the end of the century amounted to 959 lakhs; timber exports grew in the same period from 27 lakhs to 115 lakhs; petroleum and its products from 2 ½ to 57 lakhs; raw cotton from 23 lakhs to 29 lakhs; hides from 6 to 18 lakhs; spices from 2 to 8 lakhs. Similarly the imports of textiles had increased from 274 to 326 lakhs; of provisions from 14 to 84 lakhs; of machinery from 10 to 14 lakhs; of liquors from 13 to 26 lakhs; of coal from 8 to 22 lakhs. The annexation and the consequently increased openings for trade had the effect of encouraging the establishment of new commercial undertakings and the extension of existing concerns.... Mandalay Jail, 1885

|