Sentry Page Protection

Please Wait...

Irrawaddy Flotilla Co.

Snippets (2)

To search this page press ctrl + f on your keyboard will open a search box on your screen.

Enter the name you are looking for into the search box, results will be highlighted within the list.

Pressing the "enter" key will find any other instances of the name.

Enter the name you are looking for into the search box, results will be highlighted within the list.

Pressing the "enter" key will find any other instances of the name.

Irrawaddy Flotilla Airways Ltd.

In 1934 a separate company was incorporated as a subsidiary of the I.F.C. to operate aircraft in Burma, it was known as the Irrawaddy Flotilla & Airways Ltd. Messrs. Bulloch Bros. Foundry at Pazundaung had been taken over by the I.F.C. a short while before and a hanger and slipways were constructed there to house the new aircraft.

Services were operated to Mandalay once weekly, calling at Prome and Yenangyaung, also Rangoon to Yenangyaung twice weekly calling at Prome each way and Rangoon to Moulmein and Tavoy once weekly each way.

In addition, charter flights were operated where required and some interesting and unusual flights were made, such as flying over the sacred Bo tree, seven times round the Magwe pagoda and special flights to the Chindwin and Delta areas. The new company also carried out the first commercial flight to the Andaman Islands across the Bay of Bengal.

The first aircraft was a De Havilland Fox Moth seaplane with a Gipsy Major engine seating three passengers, with a speed of 75 miles per hour. This aircraft was named Zinyaw.

Later came three 4 Pobjoy engined Short Scion Senior seaplanes, seating 8 passengers each and having a speed of 110 miles per house. These were named Hintha, Karaweik and Shoay-Lin-Yone.

The pilots were on loan from Imperial Airways and one of them was Capt. Esmonde, who later was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his gallant attack on the Scharnhorst and Gneisnam. Other Imperial Airways pilots on loan were Captains Phillips, Burt and Satterthwaite.

As Burma was not then air-minded these services at first lost money, so a number of steamers and flats on the Bhamo services were transferred to the Airways Company.

Zinyaw came to grief by hitting a buoy in the Bassein river when taking off.

Hintha crashed on a trip to the Inle Lake.

Shoay-Lin-Yone went on fire below Yenangyaung and was burned out, the wreck sinking below Wetmasut village. Capt. Winter of the P.S. Mingalay made several attempts to take the burning seaplane in tow but without success.

Kawaweik was sold at the beginning of the war in 1939 and the airways section as temporarily closed down. No lives, either of pilots or passengers, were lost in any of the seaplanes.

Fuel depots and landing places for air passengers consisted of old double-decked steamers moored in the stream with bamboo rafts on each side in order that the seaplane could go alongside without any chance of her wings touching the steamer. At Mandalay, aircraft were taken out of the water if remaining overnight, on a carriage which travelled on a small slipway. This was situated at the Company’s Dockyard. In Rangoon there were proper concrete slips leading to the hanger.

A story told concerning the Zinyaw when she first appeared on the river. On one trip she arrived at Yenangyaung and had a passenger booked to join her for Chauk (some 50 miles further north.) The passenger was a Burma Oil official and his sister expressed a wish to join him in the flight. The pilot had just re-fuelled and was a little anxious regarding the prospects of being able to take off with two passengers and full tanks. Unfortunately the attempt failed and the seaplane had to be taxied back to Nyaunghla (Yenangyaung) where the lady disembarked and the seaplane proceeded.

Crowds of Burmans on the river bank had witnessed this and were not slow in expressing the opinion that the reason for the failure to take off was simple, he presence of a woman in the seaplane! To allay their fears and disprove such a theory the Company subsequently gave a number of free flights to Burmese women.

Services were operated to Mandalay once weekly, calling at Prome and Yenangyaung, also Rangoon to Yenangyaung twice weekly calling at Prome each way and Rangoon to Moulmein and Tavoy once weekly each way.

In addition, charter flights were operated where required and some interesting and unusual flights were made, such as flying over the sacred Bo tree, seven times round the Magwe pagoda and special flights to the Chindwin and Delta areas. The new company also carried out the first commercial flight to the Andaman Islands across the Bay of Bengal.

The first aircraft was a De Havilland Fox Moth seaplane with a Gipsy Major engine seating three passengers, with a speed of 75 miles per hour. This aircraft was named Zinyaw.

Later came three 4 Pobjoy engined Short Scion Senior seaplanes, seating 8 passengers each and having a speed of 110 miles per house. These were named Hintha, Karaweik and Shoay-Lin-Yone.

The pilots were on loan from Imperial Airways and one of them was Capt. Esmonde, who later was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his gallant attack on the Scharnhorst and Gneisnam. Other Imperial Airways pilots on loan were Captains Phillips, Burt and Satterthwaite.

As Burma was not then air-minded these services at first lost money, so a number of steamers and flats on the Bhamo services were transferred to the Airways Company.

Zinyaw came to grief by hitting a buoy in the Bassein river when taking off.

Hintha crashed on a trip to the Inle Lake.

Shoay-Lin-Yone went on fire below Yenangyaung and was burned out, the wreck sinking below Wetmasut village. Capt. Winter of the P.S. Mingalay made several attempts to take the burning seaplane in tow but without success.

Kawaweik was sold at the beginning of the war in 1939 and the airways section as temporarily closed down. No lives, either of pilots or passengers, were lost in any of the seaplanes.

Fuel depots and landing places for air passengers consisted of old double-decked steamers moored in the stream with bamboo rafts on each side in order that the seaplane could go alongside without any chance of her wings touching the steamer. At Mandalay, aircraft were taken out of the water if remaining overnight, on a carriage which travelled on a small slipway. This was situated at the Company’s Dockyard. In Rangoon there were proper concrete slips leading to the hanger.

A story told concerning the Zinyaw when she first appeared on the river. On one trip she arrived at Yenangyaung and had a passenger booked to join her for Chauk (some 50 miles further north.) The passenger was a Burma Oil official and his sister expressed a wish to join him in the flight. The pilot had just re-fuelled and was a little anxious regarding the prospects of being able to take off with two passengers and full tanks. Unfortunately the attempt failed and the seaplane had to be taxied back to Nyaunghla (Yenangyaung) where the lady disembarked and the seaplane proceeded.

Crowds of Burmans on the river bank had witnessed this and were not slow in expressing the opinion that the reason for the failure to take off was simple, he presence of a woman in the seaplane! To allay their fears and disprove such a theory the Company subsequently gave a number of free flights to Burmese women.

The Mingoon Bell

The big teak beams which held the Mingoon Bell (largest un-cracked bell in the world from 1790 until 1890) had rotted and collapsed, the bell had subsided onto its brick platform without damage so a Committee of prominent Burmans was formed to collect money for its re-hanging. (This bell, which is the second largest in the world weights 80 tons, the biggest one is in the Kremlin at Moscow but is cracked.)

By 1896 sufficient money had been collected and the bell was re-hung, on steel pillars with a large copper shackle, by George Hislop, at that time the Superintending Engineer of the Flotilla Dockyard in Mandalay.

The distance from Mandalay to Mingoon is eight miles, on the day of the lifting and subsequent re-dedication ceremony the Company ran three two funnelled paddlers P.S. Momein, Capt. Gate, P.S. Irrawaddy, Capt. Somerville and P.S. Mandalay, Capt J. Wright.

Mr Farrell was Chief Officer of the Irrawaddy, Mr Annesley of the Mandalay, (I was unable to find out who was the Chief Officer of the Momein.)

Capt. Somerville belonged to S.S. Manwyne, he was only temporarily in the Irrawaddy, which was laid up at this time.

The three steamers ran as often as possible carrying large numbers of Burmese to Mingoon and back whilst the bell was being jacked into position. The Irrawaddy House flag was flown from the Bell frame whilst the job was in progress. The Company made no charge for the lifting of bell but charged for the materials used. The bell is still hanging and Mingoon is still a place of great sanctity for the Buddhists.

Mr Trutwein - was once the Agent of the Company at Minbu and I met him in 1919 when I first started to collect Flotilla data. He retired and died shortly after in about 1923.

The big teak beams which held the Mingoon Bell (largest un-cracked bell in the world from 1790 until 1890) had rotted and collapsed, the bell had subsided onto its brick platform without damage so a Committee of prominent Burmans was formed to collect money for its re-hanging. (This bell, which is the second largest in the world weights 80 tons, the biggest one is in the Kremlin at Moscow but is cracked.)

By 1896 sufficient money had been collected and the bell was re-hung, on steel pillars with a large copper shackle, by George Hislop, at that time the Superintending Engineer of the Flotilla Dockyard in Mandalay.

The distance from Mandalay to Mingoon is eight miles, on the day of the lifting and subsequent re-dedication ceremony the Company ran three two funnelled paddlers P.S. Momein, Capt. Gate, P.S. Irrawaddy, Capt. Somerville and P.S. Mandalay, Capt J. Wright.

Mr Farrell was Chief Officer of the Irrawaddy, Mr Annesley of the Mandalay, (I was unable to find out who was the Chief Officer of the Momein.)

Capt. Somerville belonged to S.S. Manwyne, he was only temporarily in the Irrawaddy, which was laid up at this time.

The three steamers ran as often as possible carrying large numbers of Burmese to Mingoon and back whilst the bell was being jacked into position. The Irrawaddy House flag was flown from the Bell frame whilst the job was in progress. The Company made no charge for the lifting of bell but charged for the materials used. The bell is still hanging and Mingoon is still a place of great sanctity for the Buddhists.

Mr Trutwein - was once the Agent of the Company at Minbu and I met him in 1919 when I first started to collect Flotilla data. He retired and died shortly after in about 1923.

This description is from "The Photographic Expedition, Mar. 1862,

" ... Set off from Mandalay to see the enormous pagoda... on the north side is the largest bell in Burmah. A low wall of about four feet in height enclosed a considerable area, in the centre of which was a circular platform of five low terraces. Upon the platform were two pillars of solid masonry and from timbers fastened together by copper or iron bands the bell and the stout cross-beams were actually bent by its weight. The base of the bell was supported by wooden figures of couching nats or bilous and the comical expression, still visible on the faces of one or two seemed to remonstrate against the weight. There was just sufficient room to crawl under the lip of the bell. Pieces of gold, which has been thrown in evidently during the founding, were visible."

" ... Set off from Mandalay to see the enormous pagoda... on the north side is the largest bell in Burmah. A low wall of about four feet in height enclosed a considerable area, in the centre of which was a circular platform of five low terraces. Upon the platform were two pillars of solid masonry and from timbers fastened together by copper or iron bands the bell and the stout cross-beams were actually bent by its weight. The base of the bell was supported by wooden figures of couching nats or bilous and the comical expression, still visible on the faces of one or two seemed to remonstrate against the weight. There was just sufficient room to crawl under the lip of the bell. Pieces of gold, which has been thrown in evidently during the founding, were visible."

The description below is an extract from Wandering in Burma by George W. Bird, published 1897

"... The bell was cast on the opposite side of the river, on an island called Nan-dau-kyun and was brought over on two boats to the Mingun side. Canals were cut for the passage of the boats to the present site, the mouths of which, after the entrance of the boats were dammed up. The level of the water in the canals was the raised by partially filling them in and the bell brought into position between the immense posts and beams which were erected for the purpose.

After the huge beams had been passed through the shackles the dams were removed, the boats subsided and the bell remained suspended. Owing doubtless to the severe earthquakes (already mentioned above) the bell was thrown down and now lies resting on its lip, at a slight angle, leaving between it and the ground a narrow passage through which a tolerably thin individual can with some discomfort squeeze.

Burmese bells have no clappers, but are struck with a deer's horn or billet of wood on the exterior of the lip. As Yule says it would require a battering ram to elicit the music and tone of this monster.... sufficient funds having been raised the committee appointed to superintend the work entered into a contract with the Irrawaddy Flotilla Co. to raise the bell and rehang it on iron pillars. The work was successfully accomplished in March 1896 and the massive iron columns being case at the Flotilla Company's Foundry works at Dalla, opposite Rangoon... In connection with the raising of the bell a feast was held at Mingun in March 1896, which was attended by crowds of Burmans and also by the European residents of Mandalay. During the continuance of the feast the Flotilla Company with their usual foresight, ran hourly steamers day and night, between Mandalay and Mingun...

Burmah Oil Co.

Prior to the laying of the Burmah Oil Co.’s pipe line from the oil fields in the Magwe and Pakokku districts to their refinery at Syrian (Rangoon) the crude petroleum was carried in flats towed by I.F.C. steamers. This important traffic did not cease entirely after the pipe line came into commission in 1906 because some of the other oil companies preferred to transport their oil by river though they had the right to use the B.O.C.’s pipe line if they wished. When the towing of the oil flats was at its zenith, no fewer than 13 large steamers were employed on this duty. A distinctive feature of the towing of oil flats was the statutory flying of a red flag on each flat bearing the words “Petroleum Boat” in black.

Prior to the laying of the Burmah Oil Co.’s pipe line from the oil fields in the Magwe and Pakokku districts to their refinery at Syrian (Rangoon) the crude petroleum was carried in flats towed by I.F.C. steamers. This important traffic did not cease entirely after the pipe line came into commission in 1906 because some of the other oil companies preferred to transport their oil by river though they had the right to use the B.O.C.’s pipe line if they wished. When the towing of the oil flats was at its zenith, no fewer than 13 large steamers were employed on this duty. A distinctive feature of the towing of oil flats was the statutory flying of a red flag on each flat bearing the words “Petroleum Boat” in black.

Burma River Transport Co.

About 1909 the Company encountered some opposition from the newly formed Burma River Transport Company, which by 1910 had 22 steamers and 20 oil flats working for the Rangoon Oil Company. In 1909 therefore the I.F.C. had built a celebrated pair of ferry paddlers – namely – Otaru and Osaka – to shadow the activities of the B.R.T.Co. steamers on cargo and passenger services. During the ensuing year or so we find that something approaching the days of racing and intense competition amongst the early Clyde river steamers occurred on the Irrawaddy.

Otaru and Osaka were faster than Yemin and Galone (two of the rival company’s ships) and they used to follow the B.R.T. Co. steamer between Rangoon and Mandalay and whenever she made an attempt to go alongside a station to pick up passengers the I.F.C. vessel would increase speed and cut in, taking the passengers. Fare cutting between the four vessels continued until the B.R.T. Co. steamers were carrying passengers for free, while the I.F.C. vessels, in addition to carrying passengers for free, were giving each passenger a free meal or a loongyi! Naturally this state of affairs could not last long. Towards the end of 1911 the rival concern went into liquidation and most of its fleet was absorbed by the I.F.C.

About 1909 the Company encountered some opposition from the newly formed Burma River Transport Company, which by 1910 had 22 steamers and 20 oil flats working for the Rangoon Oil Company. In 1909 therefore the I.F.C. had built a celebrated pair of ferry paddlers – namely – Otaru and Osaka – to shadow the activities of the B.R.T.Co. steamers on cargo and passenger services. During the ensuing year or so we find that something approaching the days of racing and intense competition amongst the early Clyde river steamers occurred on the Irrawaddy.

Otaru and Osaka were faster than Yemin and Galone (two of the rival company’s ships) and they used to follow the B.R.T. Co. steamer between Rangoon and Mandalay and whenever she made an attempt to go alongside a station to pick up passengers the I.F.C. vessel would increase speed and cut in, taking the passengers. Fare cutting between the four vessels continued until the B.R.T. Co. steamers were carrying passengers for free, while the I.F.C. vessels, in addition to carrying passengers for free, were giving each passenger a free meal or a loongyi! Naturally this state of affairs could not last long. Towards the end of 1911 the rival concern went into liquidation and most of its fleet was absorbed by the I.F.C.

Rivers

On the Chindwin, stern-wheelers maintained services between Pakokku (on the Irrawaddy) to Homalin in summer (Pantha in winter) and Mawlaik and Homalin. Naungsankyin was sometimes the northern terminal during the high water season. The distance between Pakokku and Homalin is about 420 miles

On the Salween, several ferry services were worked, ranging from 3 to 70 miles in length, these were conducted by twin-screw launches, 20 of which were at one time stationed at Moulmein, as well as the P.S. Minsin.

Funnels and Hulls

The original funnel colouring was plain black in all probability, a red band being added when the I.F.C. was formed in 1875. What a welcome sight was this funnel on many occasions on the river to European exiles from home when expecting the weekly “English Mail” or periodical leave.

Hulls were black with red belting, but prior to 1904 a number of steamers were painted grey.

On the Chindwin, stern-wheelers maintained services between Pakokku (on the Irrawaddy) to Homalin in summer (Pantha in winter) and Mawlaik and Homalin. Naungsankyin was sometimes the northern terminal during the high water season. The distance between Pakokku and Homalin is about 420 miles

On the Salween, several ferry services were worked, ranging from 3 to 70 miles in length, these were conducted by twin-screw launches, 20 of which were at one time stationed at Moulmein, as well as the P.S. Minsin.

Funnels and Hulls

The original funnel colouring was plain black in all probability, a red band being added when the I.F.C. was formed in 1875. What a welcome sight was this funnel on many occasions on the river to European exiles from home when expecting the weekly “English Mail” or periodical leave.

Hulls were black with red belting, but prior to 1904 a number of steamers were painted grey.

|

The Thaton-Duyinzeik Railway

In 1885 a Mr Dawson built a small railway roughly 8 miles long of 2 ft. 6” gauge to connect Duyinzeik with the important town of Thaton. Mr Dawson at that time operated a service of small steam launches connecting Moulmein and Martaban with Duyinzeik and quite naturally wished to tap the heavy traffic of a large but unfortunately inland town such as Thaton. His track, however, was very primitive, there being no uniform grade anywhere and the sleepers were very little longer than the guage of the track. The rails weighed only 6.1/2 lb. per foot and the rolling stock had loose-chain couplings. There were 26 bridges between Thaton and Duyinzeik and as the plate laying gang had raised the level of the road over a period of years when making repairs, the bridges were all low and he rails were packed with wedges and packing pieces which on occasion flew out when a train passed over! The masonry of the bridges was much overgrown with vegetation and a Government Inspector reported that it was exceedingly difficult to trace the form of the bridge masonry owing to weeds and larger type of vegetation. The ballast walls were all defective except in a few bridges of more recent construction. The rolling stock consisted of 8 four-wheeled passenger coaches, two of them having hand brakes and 44 goods vehicles which were also used for passengers at festival times. There were three locomotives, he largest of which weighed 18 tons and had flangeless driving wheels. The other two weighed 10 tons and were the usual four-wheeler saddle-tank type. The railway was purchased by the Irrawaddy Flotilla Co. when they took over Mr Dawson’s launch service in 1900 and they spent quite a large amount of money in improving it, where it was possible, but short of re-laying and properly grading the road bed very little could be done. Signalling was primitive and the signals were not counter-weighted. There was a telephone between Duyinzeik and Thaton which was used to control traffic. In 1906 the Burma Railways completed the Pegu-Martaban Section which passed through Thaton, so the Irrawaddy Flotilla Co. took up the track of it little railway and sole it together with the locomotives and coaches for scrap. Thus ends the history if an interesting little railway venture. |

Flags

It appears the house flag of the Irrawaddy Flotilla and Burmese S.N. Co. was a green one bearing an encircled peacock in his pride in yellow. One of the authors recalls seeing two of these flags which were in the possession of the late Capt. Medd, the Company’s agent at Bhamo. There was also a blue flag of the same design and Capt. Medd was of the opinion that the blue flag could have been worn by cargo steamers.

This flat was probably changed in 1875 on the formation of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Co. Ltd. to that used for the remainder of the Company’s existence, namely a red, white and blue flag in vertical strips (but the opposite of the French National flag) with a Union Jack in the centre of the white band. This was also the flag of the British and Burmese S.N. Co. (Henderson Line) which company was very closely associated with the I.F.C. and incidentally, carried nearly the whole of the I.F.C. fleet (in the form of plates, angles etc.) from Glasgow to Rangoon, apart from a few vessels which made the passage under their own steam.

The change of flag may not have occurred in 1875 as Capt. Medd was of the opinion that it was not until 1885, the year of the 3rd Anglo-Burmese War, that the change was made.

It appears the house flag of the Irrawaddy Flotilla and Burmese S.N. Co. was a green one bearing an encircled peacock in his pride in yellow. One of the authors recalls seeing two of these flags which were in the possession of the late Capt. Medd, the Company’s agent at Bhamo. There was also a blue flag of the same design and Capt. Medd was of the opinion that the blue flag could have been worn by cargo steamers.

This flat was probably changed in 1875 on the formation of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Co. Ltd. to that used for the remainder of the Company’s existence, namely a red, white and blue flag in vertical strips (but the opposite of the French National flag) with a Union Jack in the centre of the white band. This was also the flag of the British and Burmese S.N. Co. (Henderson Line) which company was very closely associated with the I.F.C. and incidentally, carried nearly the whole of the I.F.C. fleet (in the form of plates, angles etc.) from Glasgow to Rangoon, apart from a few vessels which made the passage under their own steam.

The change of flag may not have occurred in 1875 as Capt. Medd was of the opinion that it was not until 1885, the year of the 3rd Anglo-Burmese War, that the change was made.

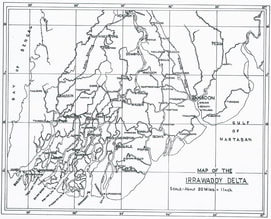

Lighting and Lightships in the Delta – Capt. Chubb writes

... Having, by 1922 been in command of steamers on the Rangoon-Bassein line for some considerable time, I made representations to the then Marine Superintendent Capt. Scott Robertson – that a few light on the Shwelaung River between Gangyaung and Shwelaung villages would be a great help to steamers, especially in the high water season when many of the islands were flooded with only a few tufts of grass visible. There has been a light at Sitchaung Bend in the high water season for several years. Capt. Scott Robertson decided to give the proposed scheme a trial and the Yandoon Agent Capt. Burke was instructed to meet me at Shwelaung and travel to Maubin with me in the T.S.S. Kowchow so that the setting and colour of the lights could be fixed. Capt. Burke would then make arrangements for the erection of the lights.

The light system agreed upon of red lights to port and green to starboard going with the flood tide. At the few places up-river where lights were used, the same system was maintained to avoid confusion. The lightships were all old Cargo boats, no longer suitable for carrying cargo and they had a light steel mast erected while the mark boat at Nangat had a tall bamboo mast carrying a white ball. Lightship crews usually consisted of two men, i.e. senior and junior watchmen receiving Rs. 10 per month. The early lights were simple colza oil globe lamps, but later up-to-date pressure lamps were supplied.... The system failed sometimes when the light-keepers, who were usually local fishermen or cultivators, forgot to light up to let the light go out before daylight.... There is a true story that, during the high water season of 1926 the Sitchaung Bend flooded badly and the Burmese light-keeper moved the light back so that he would not have to get his feet wet, with the result that next morning both up and down Bassein and Henzada express steamers were all sitting ground! It is reported that Capt. Taylor of the India came along and towed all four afloat.

... Having, by 1922 been in command of steamers on the Rangoon-Bassein line for some considerable time, I made representations to the then Marine Superintendent Capt. Scott Robertson – that a few light on the Shwelaung River between Gangyaung and Shwelaung villages would be a great help to steamers, especially in the high water season when many of the islands were flooded with only a few tufts of grass visible. There has been a light at Sitchaung Bend in the high water season for several years. Capt. Scott Robertson decided to give the proposed scheme a trial and the Yandoon Agent Capt. Burke was instructed to meet me at Shwelaung and travel to Maubin with me in the T.S.S. Kowchow so that the setting and colour of the lights could be fixed. Capt. Burke would then make arrangements for the erection of the lights.

The light system agreed upon of red lights to port and green to starboard going with the flood tide. At the few places up-river where lights were used, the same system was maintained to avoid confusion. The lightships were all old Cargo boats, no longer suitable for carrying cargo and they had a light steel mast erected while the mark boat at Nangat had a tall bamboo mast carrying a white ball. Lightship crews usually consisted of two men, i.e. senior and junior watchmen receiving Rs. 10 per month. The early lights were simple colza oil globe lamps, but later up-to-date pressure lamps were supplied.... The system failed sometimes when the light-keepers, who were usually local fishermen or cultivators, forgot to light up to let the light go out before daylight.... There is a true story that, during the high water season of 1926 the Sitchaung Bend flooded badly and the Burmese light-keeper moved the light back so that he would not have to get his feet wet, with the result that next morning both up and down Bassein and Henzada express steamers were all sitting ground! It is reported that Capt. Taylor of the India came along and towed all four afloat.

1938

By 1938 the fleet comprised some 600 vessels of all descriptions from the large paddle steamers, 326 ft. long, to the small buoying launches, including a host of barges, flats and lighters. As much information as is available as to the identity of these vessels had been incorporated in the fleet list, but is possible that this list is not complete because a number of the earlier craft may not have been registered and no office records still exist.

By 1938 the fleet comprised some 600 vessels of all descriptions from the large paddle steamers, 326 ft. long, to the small buoying launches, including a host of barges, flats and lighters. As much information as is available as to the identity of these vessels had been incorporated in the fleet list, but is possible that this list is not complete because a number of the earlier craft may not have been registered and no office records still exist.

Explanation of Crew Titles

Serang Equivalent to Boatswain and in charge of the crew under the First Officer

Burra Tindal Boatswain’s mate

Supercargo Two were usually carried. They were Anglo-Indians or Anglo-Burmese and looked after the cargo under the Second Officer.

Serang Equivalent to Boatswain and in charge of the crew under the First Officer

Burra Tindal Boatswain’s mate

Supercargo Two were usually carried. They were Anglo-Indians or Anglo-Burmese and looked after the cargo under the Second Officer.

Siam, Japan and Java - carried 28 1st Class passengers, 23 2nd Class and 2,865 deck passengers.

Map of the Irrawaddy Delta

Scale about 20 miles = 1 inch

Scale about 20 miles = 1 inch