Sentry Page Protection

Please Wait...

The Founding of Rangoon

Extracts from

A History of Rangoon

by

B.R. Pearn

published 1939

A History of Rangoon

by

B.R. Pearn

published 1939

To quickly search this page press ctrl. f

|

...But at other seasons of the year than the great festivals, Dagon remained a quiet, half-deserted spot, disturbed by none of the bustle which enlivened the commercial city of Syriam across the water, a place of which a writer of 1759 can find no more to say than that it was "a very noted Pagoda."

Towards the middle of the eighteenth century there as a revival of Mon nationalism in the Delta. When in 1740 it was learned that the King of Ava, Mahadammayaza-Dipati, was besieged in his own capital by invaders from Manipur, the Burmese Governor of Pegu, Tha Aung by name, proclaimed himself King, he “put to death the State Secretary, the two Lieutenant-General’s and the Governor of the prison and made himself King in Pegu. This ruler was very harsh and cruel and reigned only a month and a half.” He was murdered by his officers and the King then sent his own uncle, who established a new Governor who would be faithful to his allegiance, but this Governor “was very avaricious. He took bribes in gold and silver and in coin and made great distress for the people. He ruled but four months and twenty days.” The weakness of the King’s power and the misgovernment of his officers encouraged a revolt and the Mons, rising in rebellion, completely overthrew the Royal administration. The son of a former rebel Myosa of Pagan who had fled into the Karen country in 1714 when Taninganwe, his nephew, became King, was set up as King of Pegu under the name of Smim Htaw Buddhaketi. There was little resistance from the Burmese, indeed, for some years the Mons were able to carry out raids on Upper Burma. But Smim Htaw Buddhaketi was not the type to lead his people in wars and in 1747 he abandoned the throne which was held for eighteen days by a monk, Nai Caran Khuin, who was then replaced by a Mon Lord, Binnya Dala, who had formerly served the Burmese King as Master of the Elephant Stables at Pegu and was Smim Htaw Buddhaketi’s father-in-law. The Mons under his leadership continued their raids on Ava which in 1752 they sacked and burnt. It was at this point that the great Alaungpaya rose to prominence as leader of the Burmans and began to re-establish the Burmese power. Having defeated the Mons in Upper Burma, he pursued them southwards and in February 1755 entered Prome. By May of the same year he had entered Dagon. His conquests were marked by great cruelty which spared neither age nor sex: “His Majesty Aungzeya was of a very fierce and cruel disposition and made no account at all of life. He put to death many monks and their iron alms-bowls and silk robes were taken away and the homespun robes were made into foot mats. Of some they made pillows, of some they made belts and of some they made sails. The monks’ robes were scattered all over the land and water.” It is also said that when he took Pegu he found more than three thousand monks in the place and that he had them all put to death. It would appear that Dagon escaped the worst of these disasters, no attempt was made by the Mons to hold the town ..... The Mons were better equipped than the Burmans in arms and ammunition and had the further advantage of enjoying the assistance of the French establishment there (Syriam) which was under the command of the Sr. Bruno. Alaungpaya’s obvious course was to seek the assistance of the rivals of the French, the English, who were now established at Negrais and had almost deserted Syriam and as early as March he had approached the head of the factory at Negrais, but his proposal was without effect, for the policy of the East India Company was to maintain strict neutrality in the contest, since their commitments in India were too great to allow of further liabilities elsewhere. After occupying Dagon Alaungpaya received a visit from Bruno, who professed a desire to congratulate him on his conquests, but the King realised that no sincere assistance could be looked for from that quarter and in June, a month or so after entering Dagon, he despatched a second mission to Negrais bearing various presents and since it seemed evident that the Burmans were the winning side, the English sent two officers to him with a present of, among other items, a twelve-pounder gun, three nine-pounders, eight shot and four chests of powder. Meanwhile, Alaungpaya had persuaded the English shipwright, who was almost the only Englishman still resident at Syriam, to come to Dagon and with him came four English ships that happened to be in the port. The English had suffered much at Syriam from the Francophile propensities of the Mons and were doubtless glad to place themselves under the protection of the Burmans, so much so, that Alaungpaya appears to have received overt assistance from them, for when in May, a week or two after the King’s arrival in Dagon, the Mons crossed the Pegu river and established a stockade at Tamwe to the north-east of the town, Alaungpaya had the aid of “Indian soldiers” from the four ships in expelling the Mon force. At the beginning of June another English vessel, the Arcot appeared in the river in need of repairs and the shipwright, Stringfellow by name, sent a message urging Capt. Robert Jackson, to come to Dagon where the King would give every possible assistance. On the sixth June, the Arcot anchored off Dagon. Alaungpaya was at once visited by a Company’s officer, John Whitehill, who happened to be on board, Whitehill gave him a present of a fowling-piece and two bottles of rosewater, the King extended to him a courteous reception, promised the needed assistance of carpenters and caulkers and also agreed to send river boats to Negrais with letters. But Alaungpaya wanted a quid pro quo, the Mons had the aid of the French vessels that were in the port of Syriam and under their protection might come up the river and attack Dagon, he therefore needed guns. So the following day he invited all the Englishmen of the various ships to come shore and in their absence sent men to demand all the guns, small arms and ammunition that the Arcot carried as well as a statement of her cargo. Jackson, who had not gone ashore, replied that this demand was contrary to established usage and that rather than comply he would go to Syriam. The day after, the Burmans came and threatened to take the guns by force, but Jackson prepared to resist and made his ship ready to sail. Alaungpaya, having no desire to see his enemies strengthened by the accession of the English vessel, sent his son to explain that the demand was made under the apprehension that it was the custom at Syriam to land all arms but that if it was not the custom the demand would not be persisted in. Nevertheless, the Burmans managed to get possession of all the arms and ammunition of the country vessel Elizabeth that had come up from Syriam before the Arcot arrived. Alaungpaya was no doubt disappointed, but he could not afford to alienate the English at the moment, especially as the Negrais staff seemed well-disposed and sent him at this juncture a dozen muskets and some powder as a foretaste of the heavy guns which were to come later. Moreover, it was not possible for him to stay at Dagon any longer, a son of Mahadammayaza-Dipati had effected a rising in Upper Burma and Alaungpaya left Dagon towards the end of June to secure his authority in the north. The rains had begun and perhaps he hoped that weather conditions would prevent much activity during his absence. He had taken measures for the safety of Dagon, a new town had already been planned and a moat and fortified gateways had been projected, while a large force was left to hold the town under Zeyananda who had been appointed Wun or Governor, further, Alaungpaya ordered the people of villages which he passed to prepare boats against his return, “having appointed about 15,000 men to maintain the Post at Dagon......" The Mons took advantage of his departure to made several attacks. Like Alaungpaya, they realised the effect of the English ships might have on the fortunes of the day and even before Alaungpaya departed they had sent a letter to Jackson stating that an attack on Dagon was impending and asking the English not to fire on their boats and at the same time offered Jackson a friendly welcome at Syriam. Jackson, who was disgusted because the help in repairing his ship which Alaungpaya had promised had not in fact been forthcoming, was inclined to listen to such suggestions, the more so as Alaungpaya’s departure seemed to promise success for the Mons. So he replied that he would not oppose the Mon forces and that he would come down to Syriam at the first opportunity. A few days afterwards the Mons attempted a surprise attack, their boats coming up the river with the night tide while another force crossed the Pegu river and advanced by land. The boats, however, were repulsed by the fire of the Burmans who lined the bank of the river, while the land force, finding that the Burmans post on the Pagoda Hill could be carried only by assault and disheartened by the failure of the attack from the river, made only a feeble attempt and after sporadic firing had gone on through the night and most of the morning, the Mons withdrew. By noon the attack was over. During this affair the English remained strictly neutral but the Burmans suspected them for that very reason of favouring the enemy since Alaungpaya seems to have extracted from them some sort of promise that they would aid his men in the event of an attack The Burmans were not far wrong in their surmise, a week later another message came from the Mons announcing a further attack and to this Jackson and the other English officers replied that if the Mons would aid them to escape from Dagon they would give active assistance in the fight. They at the same time gave the Mons information about the strength of the Burmans, which consisted of eight river-boats, of which nine were armed with guns, a Dutch Brigantine which they had commandeered and manned with their own men and two guns mounted on shore. The Burmans, however, became aware of these conversations and demanded a definite assurance that if the Mons attacked the place the English would resist them. The English replied that without express orders from the Company they must remain neutral, but that if the Mons attacked them they would assist the Burmans. The latter were far from being satisfied with this and kept a strong guard of boats around the Arcot for several days. Meanwhile, the Mons, assured of the assistance of the English ships which, they hoped, would give certain victory, prepared for battle and early one morning the Mon flotilla of two hundred boats and one xxxx, headed by two French vessels, could be seen down the river. They had dropped down the Pegu river with the tide overnight and lay at the junction of that river with the Hlaing river, waiting for the turn of the tide to carry them to Dagon. As soon as daylight enabled the enemy to be seen, the Burmese commander sent an urgent message to Jackson demanding his support, but, in the words of Jackson “very little notice was taken of this application.” Owing to the time of the tide, it was two o’clock in the afternoon before the flotilla arrived off the town. The French ships anchored and opened fire with their cannon while the Mon musketeers commenced firing at the Burmese boats. The Burmese had withdrawn their boats into a creek, probably the old creek running up to the Sule Pagoda, where they hoped to be protected by a small battery consisting no doubt of the two guns mounted on shore, the existence of which had been reported to the Mons, these guns had been placed behind hastily constructed works in a mango grove by the river bank. As soon as the firing commenced, the English ships also began bombarding the Burmese position and unable to withstand the combined force of the enemy artillery, the Burmese were compelled to abandon their boats and take shelter among the mango trees. There they put up a determined resistance and though their cannon were not well managed, nevertheless they managed to do some execution with their musketry, two Mons killed on board the Arcot. It appeared to the French and English that if the Mons had gone in-shore they could have taken all the Burmese boats, but they were afraid to face the Burmese musketry at close quarters and despite the persuasions of Europeans they remained out in the stream. Firing went on until nightfall and after dark the English ships moved farther out into the stream, to be out of range of the Burmese muskets. The bombardment went on for seven days and then having exhausted their ammunition and achieved nothing, the Mons withdrew. The attack had been ill-managed, no diversion was made by any land force and the Mons refused to engage in hand-to-hand fighting. Thus their seven-day attack left the Burmese still in possession of their fortification. When the Mons returned to Syriam, the English ships went with them. Jackson, who had apparently gone to Syriam after the first day’s fighting, afterwards explained his conduct in preferring the Mons at Syriam to the Burmese at Dagon on the grounds that he was sick with dysentery and needed medical attention from the doctor attached to the French factory “there everything was to be got for his assistance, at Dagoon nothing, nor had they seen a fowl since they had been there and no water but what was very bad, which had thrown him into a bloody flux and a strong fever.” For the time being Dagon was safe but its position was precarious, for now the Mons were reinforced by the English ships as well as the French. The King was greatly angered by the conduct of the English in assisting his enemies, when the mission from Negrais bringing the cannon reached him at Shwebo in September, he expressed his wrath “Your ships that were at Dagon with Mr Whitehill, I treated with kindness,” he said, “and supplied them with what they wanted and at my leaving that place, to come here to keep our fast, desired him that, in case it should be required in my absence, or an emergency, to assist my people, or at least not to join the Peguers against them, which though he promised to observe, yet was the first that fired on them.” This episode implanted in his mind a suspicion of the English which was never eradicated and which led to the massacre of the English at Negrais when opportunity offered four years later. Alaungpaya now sent a new commander, Minhlaminkaungkyaw, to Dagon, who brought reinforcements with him and took energetic measures to improve the defences. At Syriam, meanwhile, preparations were in hand for a further attack on Dagon and the English were compelled to take part in this also, it being made clear to them that unless they rendered such assistance they would not be allowed to depart. The English had found the Mons if anything even less easy to deal with than the Burmese, the Mons also were suspicious of their good faith and when the chief of the Negrais factory wrote demanding the surrender of four guns belonging to the English factory at Syriam, the Mon commander refused, saying that “he knew Mr Brooke wanted to give them to the Buraghmahns that he might get some rubies from the Dagoon Pagoda.” In December Dagon endured another onslaught of even greater magnitude. Three English ships, one French ship, the Snow belonging to the Mon King and three hundred boats participated, while ten thousand men were landed to march against the fortification on the Pagoda Hill and at the mango grove. The Burmans found it impossible to hold the town and withdrew to their fort at the Pagoda. There they maintained themselves and the Mons proved unable to dislodge them. When the Burmans sent down fire-boats on the tide, the Mon flotilla and the European ships had to slip their cables and retreat, the land force, unsupported from the river, made an ineffectual attempt to storm the fort but was easily repulsed. So the attack was brought to an end. After this abortive effort the English ships were allowed to depart, though the Mons retained five of the Arcot’s guns. This was the last attack which the Mons were able to make on Dagon. Alaungpaya returned to Upper Burma with a large force and was now able to resist Syriam, which was finally taken in July 1756. The few Englishmen in the town were spared, but Bruno and the other French were put to death. Such was also the fate of the officers of two French vessels which entered the river two days after the town had been taken, they were decoyed ashore and were beheaded. The crews were made prisoners and were taken into the Royal service as soldiers. Alaungpaya then proceeded to the capture of Pegu, which he took in May 1857, but though the Mon resistance was not yet by any means finally broken, Alaungpaya’s power had still to be thoroughly established in Upper Burma, so after a further visit to Dagon in July he went northward, leaving the town under the care of one of his officers, Namdeoda. For some time he was busy repelling the Manipuris and while he was thus engaged in the winter of 1758-59, the Mons rose once more. They were able to defeat Namdeoda and re-occupy Dagon as well as Syriam and Dalla. Alaungpaya hastily came to the Delta at the news of this disaster, but meanwhile Namdeoda had gathered a force from Upper Burma and marched on Dagon. The Mons were holding the stockade by the river and also it would seem, the Pagoda Hill, for it is said that they were “encamped a little above the city.” After a stern struggle, however, the Burmans won the day and once more secured possession of the town and Hill. Dalla and Syriam fell soon after, and Alaungpaya’s arrival finally ended the rebellion. From this time onwards the Burmans suffered no serious threat to their power on the part of the Mons. Alaungpaya’s conquest is the most important event in the history of Rangoon. May 1755 marks the beginning of modern Rangoon, from this time it became the major port of Burma. Alaungpaya was resolved that Syriam must be destroyed and that some other place must become the port of the Delta. Even before he had taken the town he informed the English that “We intend to destroy Syriam,” and he fulfilled his intention, a European writer of 1782 says of Syriam that “this town no longer exists.” There were good reasons for the destruction of Syriam. Syriam had been the centre of Mon resistance and had also been the centre of European interests in the country. Alaungpaya desired to make a fresh start and to have a new port that would be neither Mon nor European by tradition but would be Burmese. Further there were sound economic reasons for abandoning Syriam. The Delta was effecting yet another change and Syriam was ceasing to have any utility as a port. The Pegu river was silting up off Syriam and sea-going vessels were finding it difficult to navigate the reach opposite the town. The English had already noted that Syriam “it seems will in a few years be almost impracticable for large ships by the increase of the sands in several places, especially before the town.” Hence they had already established a new factory at Negrais, since “the danger of going out and coming in of that harbour, is nothing in comparison of Syriam River, or the coast near it, whence the strong tides and the sands, lying at a great distance from the shore makes the entry difficult and dangerous for ships.” The English evidently regarded the whole river, for the term “Syriam River” was used to imply the Rangoon River as unsatisfactory and would have preferred the new port to be elsewhere. But Dagon was not so dangerous as Syriam, where the sandbanks had developed “especially before the town” and moreover, Alaungpaya would not be willing to establish his port at or near Negrais where the English were in possession, so that Bassein was ruled out, the more so as it had no through river connection with the main Irrawaddy in the dry season. If a new port had to be cleared, Dagon already a place of commercial importance at the seasons of the great festivals and near enough to Syriam to draw on the same field of trade, was the obvious place. So Alaungpaya established a new town at Dagon, which hereafter ceases to be a quiet riverside village and becomes instead a flourishing port. He gave it a new name, changing Lagun to Rangon “the End of Strife” and the war being over, he built a new town of Rangon or Rangoon as the English called it, a town which lasted for ninety years. |

|

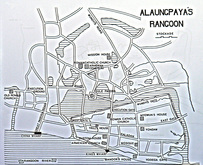

Alaungpaya's Rangoon (1)

The most striking feature of Alaungpaya’s Rangoon is the insignificance of its size. So small was it that it could all be comprised with an area between Sule Pagoda and the river on the north and south respectively, with ........ Around all four sides ran a stockade, built of solid teak piles, driven a few feet into the ground and rising in places to a height of as much as twenty feet, though in other places it was only ten to twelve feet..... Inside the stockade, which, as suburbs grew up, came to be known as “the fort” (the strict meaning of the Burmese myo) the town consisted primarily of three streets running east to west and two running south to north.... ... Thus in reality Rangoon stood on a small island and this no doubt largely accounts for its confined area. Beyond the town, where all is now dry land, were numerous tanks, some of considerable size. West of the town there was a tidal creek near the present day Latter Street and to the east was the Botataung Creek, near modern Creek Street, linking the river with the Pazundaung Creek and so forming another island known as Queen’s Island, of the present Pazundaung and Monkey Point areas.... Apart from tanks and creeks, the land was so low-lying that most of it was covered with water at high tide and during heavy rain and this was the case within the town as well as outside it. East and west, towards the distant hamlets of Pazunadung and Kemmendine, the latter being the residence of some of the King’s boatmen and the site of a guard-post, the land along the river was little better than a morass and within the stockade houses had to be built on piles to escape the rising river at high tide and the water with which the place was inundated after every shower. Drains, however, were cut alongside the streets to carry off the water and planks were laid down along each road so that the foot-passenger might avoid the worst of the wet.... As late as 1782 the streets were not paved but in 1795 they were, it is stated “tolerably well paved with brick”.... Health was possibly assisted by the practice, indulged in by the European inhabitants if not by others, of bathing in a tank south of the Shwe Dagon when one William Caldwell was brought to the town in a very low state of health after being cast away in the Gulf of Martaban, a surgeon recommended that “he should remain here for three or four months to take advantage of the mineral baths of Rangoon as the most likely remedy of restoring him to health.” This tank, whose waters were “limpid, but austere and acid to the taste,” combined natural mineral water, which on rough analysis was found to consist of a “a pure chalybeate, containing iron held in solution of the acid of sulphur or vitriolic acid, with a very small proportion of magnesia and muriatic salt.” It was commonly known as “the Scotch tank” because, it is ambiguously stated, of “the sulphurous qualities of its water.” ..... For drinking water the town was dependent on wells, the best of which were outside the stockade, for within it the wells tended to become impregnated with river water. The most potable water was obtained from a well, north of the stockade, known to the Europeans as “Rebecca’s Well” because “here at all times of the day and often at night, would be found with their earthen water pots the maidens of the town, for water and gossip.” The well was famous then as now for it excellent water and was almost the only well from which the people of the stockade had their drinking water. In general aspect the town must have been not unlike a modern Burmese village. The houses were nearly all built of bamboo matting with thatched roofs. The space underneath the floor, between the piles on which the house was erected, became a depository for filth and a home for animals and fowls. One writer unkindly states that “fowls, ducks, pigs and pariah dogs ..... added to the inmates of the house, place it on a par with an Irish hovel.” Another observer says that “the space beneath is invariably a receptacle for dirt and stagnant water, from which, during the heat of the day, pestilential vapours constantly ascent.” “The City” wrote one observer, “appeared to me very strange and such wretched houses I thought I never saw, though they are built with wood. Dogs, rats, hogs and all manner of vermin are certainly very numerous, but not more so than they are in a native town in Bengal. Houses are raised two, three, four or five feet from the ground and all underneath is hollow and filled with all manner of rubbish and filth of the house and family, which these animals feed upon and live among.” The number of owner-less swine and dogs which wandered around the town and played a part of public scavengers was frequently commented on by travellers. “Heaps of meagre swine, the disgusting scavengers of the town, infest the streets by day and at night they are relieved by packs of hungry dogs.” Timber houses were few and brick houses even fewer. It was illegal for a Burmese subject to build a brick house, for it was feared that such buildings might become centres of resistance against the authorities, but no restriction was placed on the materials used by European residents for their buildings, provided they obtained prior permission and paid a heavy tax, though in general the Europeans preferred timber houses “not from any want of brick or lime, but because the wooden houses are more adapted to the dampness of the climate. Such few brick buildings as so exist are used more as magazines than as dwelling houses.” It would appear, however, that the true reason for the preference for timber houses was the poor workmanship of the builders, “even these buildings are erected so very badly that they have more the appearance of prisons than habitations. Strong iron bars usurp the place of windows and the only communication between the upper and lower story is by means of wooden steps placed outside.” Symes, in 1795 noted that the two-story Customs House which lay more or less or the site of the present day new Law Courts, was the only lay building in the town constructed of brick. Apart from the Customs House, the principal buildings were the residence of the Myowun, which lay approximately on modern Merchant Street between Lewis Street and Sparks Street and the Yondaw, the Public Court, which lay opposite it on the south side of Pegu Place, both of these buildings were made of timber. ... The town outgrew the narrow limits within which it was first designed but it extended along the river bank to the west not to any extent northwards but not much eastwards where the ground was even more swampy than on the west. West of the stockades here grew up, along modern Strand between Maung Khine and Mogul Streets, a suburb known as Tatgale or Tackley as it was Anglicised. Here a populous area appeared, inhabited mainly by workmen connected with the ships and by prostitutes. Merchants and ships’ officers lived inside the stockade. It appears that houses were also erected between the stockade and the river..... There were also a number of burial grounds, such as the Armenian cemetery, not far from the north face of the stockade. As the ground rose towards the laterite ridge it became covered in jungle. There was much jungle also west of the Shwe Dagon, covering the present golf-course, the Government House area and Ahlone, “the whole space between the western face of the Shwe-da-gong and the left bank of the Rangoon river is covered by the densest forest.” In these jungles wild animals abounded, elephant and tiger among others, the tigers would come up to the stockade around the town in hope of seizing pariah dogs and one case is even recorded where a tiger was found within the stockade. To the east of the Shwe Dagon lay the lakes known as the Kandawgyi and the Kandawgale and beyond these the swamps verging on Pazundaung Creek. Across the river lay the town of Maingthu, where now Dalla stands. It was a moderate-sized place, “one long street” and was the residence of the Governor of the province of Dalla, for Twante had now lost its importance and with the rise of Rangoon the provincial capital of Dalla had been attracted thereto. One part of Maingthu, the Meinma Shwe Ywa, was inhabited exclusively by prostitutes. As it was the capital of the province Maingthu came to be called by the province’s own name and as early as 1895 was beginning to be known as Dalla. The town of Rangoon came within the jurisdiction of the Myowun of Hanthawady, commonly known to the Europeans of the time as the Viceroy or Governor of Pegu or of Rangoon, after 1790 he was accustomed to divide his time between these two towns and in his absence Rangoon was under the charge of the Yewun. The powers of the Myowun were extensive, he was as one holder of the office told Symes “vested with authority to adjust every matter that related to the province” he had judicial as well as executive authority and in criminal causes he and he alone had the power of life and death, though in civil suits an appeal lay to the Hlutdaw at the capital. In executive and in judicial matters alike he was assisted by the advice of a council formed of his principal subordinates, but he appears to have had the final voice, for it is said that no matter was settled contrary to his opinion. Once a year he was required to visit the Court to render an account of his stewardship. The second officer in the province was the Yewun, “the minister of the water,” the title being conferred on the Deputy-Governor of a maritime province without any necessary reference to maritime duties. The Yewun was primarily a judicial officer and cases other than those of major importance came before him. Cases of gravity came before the Myowun aided by his council. The third officer was the Sitke and the title of Sitke is generously defined by the dictionary as “a Lieutenant-General; a Magistrate.” Actually the Sitke appears to have been primarily a Police Officer, for he is defined elsewhere as a “Conservator of the Peace.” There was also an Akunwun or Collector of Customs, usually known to Europeans as the Shahbandar. There was an Akunwun or Collector of Revenue, who received the taxes for the whole of the province, the Akunwun having no jurisdiction outside the port. Other officials were the Nakhan or “Public Informer” whom Cox described as a “reporter” the Head Clerk, the Secretary and the Aweyauk or Officer to whom the arrival of strangers had to be reported. These officers were accustomed to assemble daily for the despatch of business in the Yondaw or Royal Court, where all Royal Orders were read and local affairs were discussed. They were supported by a small force of troops, some four or five hundred in number, under the command of the Sitke, the troops were armed with condemned East India Company muskets bought up by speculators and sold in Burma. There were in addition a number of official interpreters, whose services the foreign merchants and sailors were required to employ in the transaction of their business, complaints were sometimes made of their dishonesty of these “licensed linguists” and after a time permission was given to employ interpreters without restriction. The authority of the Myowun and his council extended over the whole province of Pegu or Hanthawaddy, not merely over Rangoon “all the causes and Government business which arose, I reported to the Royal Court at Rangoon and settled in accordance with the instruction sent me,” stated the Headman of Ma U township in the Census returns of 1802. Similarly the record of Kawliya township in the Census of 1783 states that fees were paid “to the revenue writers and Akunwun of Rangoon town... If there is a Myosa or Ywasa, one half of the revenue is paid to him, one half is taken for my own use. If there is no Myosa or Ywasa, one half is paid to the Viceroy of Rangoon.... Criminal cases of theft, murder and arson are sent to the Court at Rangoon Town.” These various officers who constituted the local Government, far removed from the capital and enjoying a wide measure of authority were almost completely uncontrolled, except when they quarrelled among themselves and conducted intrigues against one another which produced intervention from above. Not infrequently the Yewun would intrigue against the Myowun in the hope of displacing him and each would form a faction among the subordinate officials and the town folks, so producing conditions in which violent outbreaks seemed hardly to be avoided. The Officials were Burmese with the exception of the Akunwun, who was almost invariable a foreigner, the office being the highest that a foreigner could aspire to and occasionally the Akunwun who was at one time an Armenian. The reason for the employment of non-Burmans in this office was that a foreigner was likely to have a better knowledge of trading conditions and shipping than could a Burman. Thus for many years the Akunwun was a Portuguese, Joseph Xavier da Cruz, commonly known as Jaunsi, who first appeared in Burma in 1760 and was still employed by the Burmese Government as late as 1804. He was, it would seem, typical of the adventurers who frequented the Burmese ports, he had been gunner on an English vessel, had murdered his Captain and come to Burma with his plunder. He settled down as a respectable citizen, became Akunwun, married a widow of a Frenchman who had served in the Royal Guard and was largely responsible for paving the streets of the town and erecting the jetty at the King’s Wharf. At another time one Baba Sheen, born in Burma of Armenian parents, held the office. Later it was held by an Englishman, Rogers, a native of Windsor, who had been an Officer on an East Indiaman, had assaulted his superior and had fled from Bengal to Burma to avoid the consequences of his crime, about the year 1780, being destitute and pressed by creditors he became the slave of the Prince of Prome, the King’s second son, he adopted Burmese dress and customs and prospering in trade, became Akunwun. He had a rival in the person of Lanciego a Spaniard who had command of a privateer during the war of the French Revolution and had settled in Rangoon as a trader, then he married a daughter of the Akunwun, Jaunsi and became Akunwun himself in the course of time. Thereafter the office alternated between Lanciego and Rogers according to the fortunes of their friends at the Court. Such were the foreigners who were employed by the Burmese Government. It may be noted that foreigners were employed at other ports also in the office of Akunwun. The officials received no regular salary but lived on the fees which they were authorised to charge and on a share of the taxes. Fees were levied for example, in connection with the administration of justice, in general to the extent of ten per cent of the amount involved in the litigation and in general of all imposts half went to the King’s treasury and half to the officials, except when the King had appointed a favourite or relative as Myosa of a district to enjoy half the revenues from it. But the officials augmented their incomes by impositions of dubious legality and this is not surprising, for when the King wanted to extend his patronage he would double or treble the number of offices, thus at times in Rangoon there were two Yewuns, two Sitke’s two Nahkans, two Head Clerks, two Secretaries and even two Akunwun’s. And since all the office-holders wanted fees, extortion became the rule. |

|

Many complaints were made of the extortions of officials, when suits were tried, the officials would extract fees from both sides, often to the extent of three or four times the value of the object of the litigation. Not infrequently subordinate officials would arrogate to themselves judicial authority and keep what were called in Rangoon “justice shops” where “justice” was sold to the highest bidder. “These numerous tribunals are an endless source of gratification to the litigious, of fees and presents to the judge and others employed on the occasion. It is true, in case of grievance, redress may be had from the Viceroy, but the expense and the fees attending such an appeal generally equal, if not exceed the sum for which it is made.” The peons attendant on each officer, moreover, made it their business to encourage unnecessary litigation, since they shared the fortunes of their master. These abuses, however, arose only under the rule of a weak Myowun, a strong Myowun would require all cases to be brought to the Yondaw. When, however, a Myowun was removed from office, the interim between his departure and the arrival of his successor was utilised by the subordinate officers encouraging appeals by litigants for revision of the late Myowun’s judicial decisions, so that they obtained fees and presents for hearing case anew.....