Sentry Page Protection

Please Wait...

Extracts from

A History of Rangoon

by

B.R. Pearn

published 1939

to search this page press ctrl f

A History of Rangoon

by

B.R. Pearn

published 1939

to search this page press ctrl f

Rangoon owes its history to two factors, the Shwe Dagon Pagoda and the river The former made it a place of note in earlier ages and the latter has made it the chief port of Burma... Little reliance can be placed in legends which relate to the very early era, our extracts start in the 1700's with the Founding of Rangoon

and can be read here this section also includes Alaungpaya's Rangoon and helps to set the back ground for the first Anglo-Burmese War

which will bring the reader to the following chapter in the history of Rangoon.

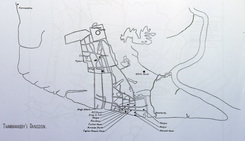

Tharrawaddy's Rangoon

|

With the resumption of authority by the Burmese officials, life in Rangoon resumed its old course. The suppression of the Mon rebellion was thorough and almost final and little further disturbance on the part of the Mons occurred during the remaining twenty-six years of Burmese administration. But while politically Rangoon remained in general quiescent, nevertheless it did not develop in commerce or progress in conditions of life. For whereas Rangoon had formerly been the principal port of Burma and had at the same time been of considerable importance as a base where armies might be concentrated to hold the Delta, Arakan and Tenasserim in check, now Moulmein appeared as a flourishing commercial centre, to a large extent replacing Rangoon as the principal port of Burma, while from the military point of view, not only was he Delta now once more subdued but also Arakan and Tenasserim had ceased to be provinces of the Burmese Empire, so that the concentration of armies at Rangoon was uncalled for except when some scheme was afoot for reclaiming Burma irredenta and that could not be until the humiliation of 1826 had to some extent been forgotten with the passage of years. Thus for a time after the First Anglo-Burmese War, Rangoon stagnated.

The system of Government of former days was restored. Once more the Myowun ruled the town and the surrounding province with the aid of his subordinate offices, such as the Yewun and the Akunwun. The Akunwun continued to be a foreigner, the Spaniard Lanciego, who had lost his office and had been cast into prison as a consequence of the general suspicion with which foreigners of all races were regarded during the War, was allowed to return to his employment, though he did not hold it long, for he was replaced by a Portuguese (or Goanese) Antony Camaratta, about ten years later. The principles on which the administration was conducted remained unchanged.... In 1830 there were only four or five Europeans in Rangoon, and the number continued small, probably never exceeding a dozen all told. They were ship-builders and dealers in timber and cheap cottons. Ship-building, however, like the teak trade, tended to decline. The competition of Moulmein helped to undermine the Rangoon ship-building industry, and though a few ships were still built their construction was weak and they could not rival the products of the new ship-yards of Tenasserim. As in earlier times, lack of iron was a fundamental weakness. Coir cables were generally used, for example; and thus one vessel, the “Tigrand” built by an Armenian, Sarkies Manook, was lost on its first voyage because its cables parted during a squall off the Nicobars. The port rules, moreover, encouraged eccentricity of design; ships of not more than sixteen feet beam were exempt from anchorage dues, and one ship-builder constructed a vessel of three hundred tons, the “Colonel Burney” which conformed to the normal model of ships to within two or three feet of the deck, from which point the hull sloped sharply inwards so that the deck should measure only sixteen feet. The same ship-builder – May Flower Crisp, who had piloted the invading force up the river in 1824 and subsequently entered into partnership with a long established merchant R.J. Trill – experimented further by building a ship with two keels, giving her the appropriate name of “Original.” The ship-building yards still lay on the tidal creek which ran through Tatgale, (this suburb is outside the stockade on the west) near the line of modern Latter Street. It appears that Maingthu, however, had sunk into complete insignificance, for there is no evidence of any industry there. In general appearance, the city of Rangoon had not changed at all. “So wretched a looking town of its size, I have nowhere seen,” writes a traveller of August 1836. “The city is spread upon part of a vast meadow, but little above high tides and at this season resembling a neglected swamp. The approach from the sea reveals nothing but a few wooden houses between the city and the shore. The fortifications are of no avail against modern methods of attack. They consist of merely a row of timbers set in the ground, rising to the height of about 18 feet, with a narrow platform running round inside for musketeers and a few cannon, perhaps half a dozen in all, lying at the gateways in a useless condition. Some considerable streets are back of the town, outside the walls. The entire population is estimated at 50,000, but that is probably too much. There is no other seaport in the empire, but Bassein which has little trade and the city stands next in importance to Ava, yet there is nothing in it that can interest the traveller. A dozen foreigners, chiefly Moguls have brick tenements, very shabby. There are also four or five small brick places of worship for foreigners and a miserable Customs House. Besides these, it is a city of bamboo huts, comfortable for this people, considering their habits and climate but in appearance as paltry as possible, Maulmain has already many better buildings... The streets are narrow and paved with half-burnt bricks, which, as wheel-carriages are not allowed within the city are in tolerable repair. There is neither wharf nor quay. In four or five places are wooden stairs at which small boats may land passengers, but even these do not extend within twenty feet of low water mark. Vessels lie in the stream and discharge into boats, from which the packages, slung to a bamboo, are lugged on men’s shoulders to the Custom’s House.” It would thus appear that the King’s Wharf had fallen into disrepair by 1836..... True, that by the Treaty of Yandabo it had been stipulated that no arbitrary exactions should be levied on British ships and that guns, rudders etc. need no longer be landed and that the supplementary commercial treaty of 1826 provided for the free ingress and egress of British merchants, who were to be allowed to carry on their trade unmolested, but Crawfurd, who negotiated the commercial treaty, endeavoured in vain to secure freedom of export of the precious metals and equally failed to obtain any relaxation of the law prohibiting the emigration of females. Complaints of arbitrary exactions continued to be made..... For some years after the War, moreover, the heavy taxation necessitated by the large indemnity payable under the Treaty of Yandabo handicapped trade... Under the prevailing conditions it was inevitable that trade should to some extent pass to the new port of Moulmein, where such impediments to commerce were unknown and through which teak, the major export of Burma, obtainable from the Salween valley, could be exported as easily as through Rangoon. But a good deal of raw cotton continued to be exported to the mills of Dalla, the amount increasing to about 2 million pounds weight annually..... A good deal of smuggling of gold, silver and precious stones went on , as in former days, despite the penalties imposed on those detected in such crimes. According to some accounts, however, Rangoon was at this period a dying port. A visitor to the town in the 1830’s states that the arrival of a European ship was “comparatively rare” and in the recollections of a resident of that period, “ as the trade of the port was very small and as the rules for export were often prohibitory, a vessel of 20 to 40 tons with now and then a Burmese “Kattoo” was able to convey from port to port all the fish, ngapi, betel nut, tobacco, chilies etc. which then formed the staple of Rangoon commerce. These vessels were rarely full of freight.”.... The population of the town was locally estimated during this period at fifty thousand.... Probably the number of inhabitants was still not more than ten thousand. Of these a number were, as in former days, foreigners, Armenians, Parsis, Muslims, Hindus, a few Chinese and a handful of Europeans, engaged in trade and industry on the town.... ...an official record of 1838 shows that in that year there were ten European-British subjects in Rangoon, two British subjects of partially Asiatic blood, five Armenian-British subjects, twelve Parsis from Bombay and seven other British-Indian subjects. These were ship-builders and dealers in timber and cheap cottons. Ship-building, however, like the teak trade tended to decline. The competition of Moulmein helped to undermine the Rangoon ship-building industry.... The names of the foreigners:-

|

|

... Coir cables were generally used, for example, and thus one vessel the Tigrand, built by an Armenian, Sarkies Manook, was lost on its first voyage because its cables parted during a squall off the Nicobars.

The port-rules, moreover, encouraged eccentricity of design, ships of not more than sixteen feet beam were exempt from anchorage dues and one ship-builder constructed a vessel of three hundred tons, the Colonel Burney, which conformed to the normal model of ships to within two or three feet of the deck, from which point the hull sloped sharply inwards so that the deck should measure only sixteen feet. The same ship-builder – May Flower Crisp, who had piloted the invading force up the river in 1824 and subsequently entered into partnership with a long established merchant R.J. Trill – experimented further by building a ship with two keels, giving her the appropriate names of Original. The ship-building yards still lay on the tidal creeks which ran through Tatgale near the line of modern Latter Street. It appears that Maingthu, however, had sunk into completed insignificance, for there is n evidence of any industry there. The foreigners who frequented the town seem to have been of a turbulent type. Perhaps the disaster which had befallen the Burmese army in 1824-26 had encouraged them to treat the local authorities with contempt. Whatever the reason, it is apparent that some of them were continually at loggerheads with the local Government. For example, May Flower Crisp was several times imprisoned for refusing to shikho the Myowun in the street and feeling himself aggrieved on one occasion he “went to the Rangoon Woongyee’s house, treated him with disrespect and used indecorous language.” The cause of the episode was the refusal of a request which he had made for a reduction of port dues, but “on the Viceroy producing the Commercial Treaty and explaining that no more than the customary duties were demanded, Mr Crisp said that the Treaty may be binding to you and the Company, but if we do not get justice we will go to the Company’s master and other words so offensive to the Woongyee that he got up and quitted the hall.” By the Company’s master” he evidently meant the Imperial Government at Westminster. It is not without significance that the official list of British subjects resident in Rangoon in 1838 adds the comment “Character bad,” after the names of some of them, one of them David Staig, being described as “a very unprincipled man and of a very violent disposition,” while one of the Anglo-Indians, James McCalder, is stated to be “a receiver of stolen goods, keeps a grog-shop.” Even those who escaped the condemnation of the official records, appear often to have been in difficulties with the authorities, usually for smuggling gold and silver out of the country. In the earlier times the foreign mercantile body had been supplemented by the presence of missionaries, but after the War the American Baptist Mission practically ceased to exist for far as Rangoon was concerned. The mission house in the suburbs, destroyed during the war and the subsequent rebellion, was never re-built, a house was taken in the town in its stead but though sporadic efforts were made to keep the mission alive, these had little success. Missionaries, as before, were tolerated only in the capacity of ministers to the foreign inhabitants, as such they were welcome and any attempt at preaching to the indigenous inhabitants was regarded with suspicion and alarm. “It is not possible,” wrote an official of the American Baptist Mission in 1836 “that any native would be allowed openly to confess that he had changed his religion,” for “the spirit of persecution has never intermitted at Rangoon and the acts of it very seldom.” Indeed, he expressly states that missionary enterprise in Burma proper had been a dismal failure and that the Baptist Mission in the Burmese Kingdom “may almost be said to be extinct.” Again in 1846 Judson wrote that no missionary had for a long time attempted to establish himself in Rangoon and when he went to the town in the following year he complained that “it is not as a missionary or propagator of religion but as a minister of a foreign religion, ministering to the foreigners in the place that I am well received,” and a month later, “the Governor of Rangoon.... received me in the most kind and encouraging manner, but only in the character of a minister of the Protestant religion, coming to minister to the foreigners” For all practical purposes, the mission ceased to exist in Rangoon after the war. Though the mission-house no longer existed, the cemetery attached to it was still in use. It had become the general European burial ground and after the missionaries abandoned Rangoon it was secured for this purpose by a merchant names Spiers, who obtained a grant of land from the Myowun. It continued in use up to and shortly after the War of 1852. ... For some years after 1826 foreign residents had the protection of a British Officer, Lt. (later Capt.) G.H. Rawlinson, assisted for a time by Capt. Robert Ware, remained in Rangoon after the evacuation in December 1826 for the purpose of receiving the remaining instalments of the indemnity due under the Treaty of Yandabo and these officers acted as Political Agents for General Campbell, who was still Chief Commissioner for Burmese affairs. In their capacity of political assistants, they fulfilled in effect the functions of diplomatic officers. Thus they intervened when, as early as 1827, a monopoly of all export trade from Burma was given, in complete defiance of the Treaty of Yandabo and of the commercial Treaty, to Sarkies Manook, and a heavy duty was imposed on all British goods brought into the harbour even if they were not intended to be landed but were merely in transit to other ports, the intention being that Manook should in return for the monopoly pay the interest on the overdue instalment of the indemnity. Rawlinson’s protest, however, was effective and monopoly and duty were both abolished. Again, when May Flower Crisp indulged in his altercation with the Myowun, Ware held an enquiry and found that the complaints made against the rates of port-charges were unreasonable and that the more respectable merchants had not been part to the affair, he further assured the Myowun that Crisp’s behaviour was improper and that British merchants were expected to make representations only through the British Officers stationed in Rangoon.... The Treaty of Yandabo did in fact authorise the maintenance of an agent in Burma though no system of capitulations was provided for and the upshot was that for the purpose of supervising the British subjects in Burma and for other reasons in 1830 Col. Henry Burney, whose father, Richard Thomas Burney, had died in Rangoon in 1808, was sent to Burma as Resident. The records of the Residency shed a good deal of light on the conditions in Rangoon at this period. Thus a few months after Burney’s arrival he had to deal with a curious testamentary case. A Capt. Sumner, who died in Rangoon, had left considerable property in the form of merchandise and a ship that was being built in the ship-yard but certain creditors of Madras and Pondichery had claims against him. Two British subjects of bad character, Low and McCalder, produced a will purporting to be signed by Sumner, appointing them executors and they proceeded to dispose of the property. The creditors asserted that the will was a forgery and that Sumner’s name had been affixed to it “with his own hand after his death.” Burney secured an injunction from the Hlutdaw and so was able to satisfy the creditors’ demands. Again, the European merchants complained that the Yewun was taking bribes from debtors in consideration of releasing them from imprisonment and Burney was able to secure an order from the Hlutdaw that “when a debtor is confined, he must be deprived of his liberty according to the laws and customs of the Burmese and not allowed to go to feasts or go about the city like another man who does not owe money. It must be the duty also of the Woongyee to assist all merchants to recover their lawful debts without any delay or trouble.” Burney also endeavoured to persuade the Hlutdaw to permit the export of precious metals as such a measure would “certainly facilitate and extend commerce in this country although our merchants at Rangoon do not appear to experience much difficulty in smuggling specie out of the country – a practice which as long as it is their interest to pursue no regulation of the Burmese Government will ever be able to prevent. Even the vigilance of the new Custom’s Master at Rangoon, Mr Lanciago, does not appear to have enhanced the difficulty much.”...... He was able to intervene with success, however, when certain merchants suffered the loss of over twenty thousand rupees silver which was discovered and confiscated by the customs authorities when they were endeavouring to ship it out of port. The merchants concerned, Messrs. Roy and Lane were “the most respectable British merchants in the Kingdom” and “this was the first instance of their having been detected violating its law,” so in consideration of these circumstances the Hlutdaw refunded the money. .... when “two European, natural born British subjects, one named Bartly who had lately come from Moulmein where he was employed as a shipwright and the other a deserter from H.M. 41st Regt., have been apprehended by the Burmese authorities and confined in irons for having robbed and murdered a lascar in the suburbs of Rangoon.” the Myowun was reluctant to execute the criminals under Burmese law and he was able to solve his difficulty by handing them over to the Resident to be deported to Calcutta for trial there, the witnesses in the case being later sent to Calcutta also by the Wun’s orders..... At the same time Burney’s duty required him to spend most of his time at the Capital and after Rawlinson left in 1833 there were long periods when there was no British representative in Rangoon. Burney therefore proposed that Dr. G.T. Bayfield, who was surgeon to the Residency, should be posted to Rangoon to guard commercial interest, but the Government of India declined to sanction the expenditure involved..... “during the absence of the Resident from Rangoon, British subjects have no protection”.... The death of the Wungyi Maung Khaing in 1835 and the appointment as Myowun of the Queen’s Wungyi, Maung Wa, “an arrogant, obstinate old man,” increased the difficulties and caused many protests to be made to the Government of India..... ... “A merchant at Rangoon cannot trade there extensively without smuggling specie out of the country in defiance of the established law,” the situation would certainly arise that the British Consul would come into conflict with the authorities.... If, he suggested an official of the Consul were stationed in Rangoon and if also one or two British warships visited the port every year, British influence would be increased and the troubles of the merchants would largely solve themselves. The Chamber of Commerce had proposed the appointment of Capt. William Spiers, the purchaser of the English cemetery, who was a half – pay naval Lieutenant settled in Rangoon as a merchant, but the remaining merchants bore out Burney’s comment on the jealousy rampant among the mercantile community by submitting a protest through the troublesome May Flower Crisp, who not only objected to the appointment of Spiers on personal grounds but opposed the whole suggestion of establishing the consular office, saying that that the proposal was contrary to the Treaty of Yandabo and would therefore encourage the Burmese Government also to disregard that Treaty, an argument with which Burney failed to agree. Meanwhile, complaints of ill-treatment continued, as the case of James Dorrett of the schooner London illustrates. In May 1836 when the schooner was going down the river, it was boarded by two Burmese Officials and a party of men, who beat Dorrett, the Commander, bound him hand and foot and stole over three hundred rupees worth of silver. Dorrett also complained that his crew had been encouraged to desert and that when he protested he was threatened with being put in the stocks. The Resident obtained an order from the Hlutdaw for the punishment of those responsible, but evidently the position of foreign traders and ships’ Captains in the port of Rangoon was liable to be very precarious. After October 1837, when Burney finally left the country, Dr. Bayfield was stationed at Rangoon in charge of the Residency pending the appointment of a new Resident......Thus a trader from Tavoy, one Nga Nyo, complained that the Yewun had demanded an unauthorised perquisite of two bundles of wax candles, value two rupees and that the officers at the Chokey at Danot had also levied improper charges of two rupees, Bayfield was able to recover the amounts. Mg Shwe Bo of Mergui was granted a certificate showing that he was a British Subject, as he wanted to go into the interior to trade. On occasion Bayfield intervened to soften the rigours of the law. Mr Snowball, of the schooner Louisa, who had been trading to Rangoon for many years, was accused in the Myowun’s court of assaulting a wharf cooly and was fined Rs. 60 plus costs. He refused to pay the costs and was therefore incarcerated in default of finding security for the payment. Bayfield induced the Myowun to release him, his official interpreter going bail and next day as a favour the Myowun ‘s reduced the costs by half, on Bayfield’s representations, because Snowball was a poor man and had been led into the assault by the abusive language of the cooly. Again, he intervened to protect a woman of Moulmein, Ma Mentha – Ma Mentha had been sold as a slave by her mother to one Shwe Ao for 12 rupees, some twenty years before and had lived with him in Rangoon until the Anglo-Burmese War. When the British left in 1826 she went to Moulmein and married there. Now she came with her husband to the Shwe Dagon festival, was recognised by Shwe Ao and arrested at his instance. At Bayfield made a request to the Myowun who ordered her release and severely censured the officer who had arrested her. Bayfield appears, indeed, to have exercised a consular jurisdiction over British nationals in the port as Burney had formerly done. Thus in his diary is recorded the following: “Capt. Nicols, formerly of the schooner Hebe, charged with forcibly entering private house at between 9 and 10 o’clock last night and offering some violence to a Burmese female, the wife of an officer of Government. Charge denied and as it was too late in the day to collect the evidence, 10 o’clock tomorrow morning was appointed for the investigation... The complaint against Capt. Nicols have been satisfactorily proved and his own witnesses admitting he had been attending a convivial party and was not very sober and committed himself, I sentenced him to pay a fine of forty rupees with which the Yewoon expressed himself satisfied. Had the Yewoon insisted upon inflicting the full fine, as established by law, the amount, including law charges, would have been one hundred and two rupees. This, however, would have been an act of severity, as Capt. Nicols does not appear to have used any violence beyond entering the house and seizing the woman’s hand.” As it is stated that the Yewun sent his case to Bayfield for trial it appears that the local authorities were still ready to recognise the establishment of a consular jurisdiction for dealing with foreign nationals. Further, the Resident required all British subjects to register themselves at his office, as this measure “might operate as some check upon those of questionable character and fidelity.” Thus the Residency exercised very important functions apart from its purely diplomatic duties. The readiness of the Burmese authorities to recognise consular jurisdiction is explained by the turbulent character of the British nationals in the port, who must have been extremely troublesome to the officials and the violence of their conduct and the jealousies which divided them are well illustrated by the following extract from a letter written by May Flower Crisp at a period when there was no British representative in the town to deal with such cases: “The other night Mr Staig went on board his schooner and there quarrelled with his Captain. The Captain being in bodily fear armed himself with a sword. Mr Staig was wounded in the wrist. The Captain was put in the Customs House. On the following morning the Woonduck sent for Mr Brown and his two messmates, Roy and Spiers, the latter was sick. Biden was sent for and Mr Larkin’s nephew, when the case was investigated and the Captain remanded to prison and eventually put in treble irons. On learning that this select jury had omitted to protest against viewing the Captain in the light of aggressor, the whole of the European community (Roy, Brown and Spiers excepted) conceived the best step would be to proceed to the Woonduck in a body. Nevertheless this minority objected and thereby destroyed unanimity. Under these circumstances I waited on the Sharbundah and convinced him the Mr Staig was the aggressor. Capt. Rausman addressed a letter to him to the same effect. I explained to the Sharbundah that on Government refusing the security of us merchants, we would have no other alternative but of solicit of our Government to send hither a ship of war as security, in as much as Capt. McGrath might die in jail. The next day the Woonduck sent for the jury when the Captain was liberated on bail. Had we gone in a body two pilots would have avowed that Mr Staig had said he had a pistol and a dirk. Now, however, that are afraid, Mr Staig being in debt to them both which, with his influence with the Woonduck, renders him an object of terror to them. This statement not only illustrates the troublesome character of the foreigners, with their violence of conduct and their threats of visitations by ships of war, but also suggests that despite the frequent complaints of oppressive actions on the part of the Burmese officials, the latter were in reality anxious, at least on this occasion and therefore presumably on other occasions also, to be reasonable and conciliatory, since the more respectable merchants were constituted a board of assessors to advice the Wun in his judgement. It may be noted that this episode occurred at a time when relations between the Burmese Government and the Government of India were more than usually strained.... Another problem with which Bayfield was concerned arose from reforms which King Tharrawaddy had instituted after his accession in 1837. With a view to encouraging trade, the King had reduced certain port dues and had also abolished the old tax of ten per cent on the wages of coolies and carpenters employed in connection with the shipping. But further he wished to systematise the conditions under which cooly labour worked. So far such labour had been of a casual nature, the merchants employing coolies direct, orders were now issued that the coolies were to be organised into gangs under the control of the Akunwun, who would see that the gangs were employed in rotation without favour or selection. The merchants objected to this proposal, even though it was also laid down that there should be no increase of wages and although the Myowun reiterated the order, they refused to work the scheme. Bayfield was sympathetic to the point of view of the Burmese authorities, but since the merchants stood firm he induced the Myowun to allow them to hire their coolies in the bazaar as formerly at competitive rates of wages. In July 1838 Col. Benson arrived in Rangoon to assume charge of the Residency. He was well received by the Myowun and salutes were fired by the battery as well as by H.M.S. Rattlesnake on which he had come. The Yewun met Benson at the wharf and conducted him in procession through the streets which were lined with troops and crowded with spectators, to the house where Burney had formerly lived. This house stood on a site at the junction of the present Merchant Street and 36th Street, it belonged to Sarkies Manook and was rented at Rs. 200 a month. It is described as being “ like a large barn.” Benson desired to proceed to the Capital, but King Tharrawaddy, who, in accordance with the Burmese view that a monarch was not bound by treaties entered into by his predecessor, declined to recognise the Treaty of Yandabo, was most reluctant to admit another Resident, whose presence at the Capital he regarded as a restriction on his sovereign authority.... Benson, however, insisted on going to the Capital and his determination led to a marked change in the Myowun’s attitude. He became distinctly less friendly and when on Benson’s departure the usual salute was fired by H.M.S. Rattlesnake, he sent a strong protest, asserting that the firing of salutes, even salutes of muskets, was contrary to law and custom, while Bayfield, who remained in charge at Rangoon after Benson left, was put to a great deal of inconvenience. Thus the Myowun refused to transact any business with him and ordered him to vacate the house in which he was living. Bayfield then went to a house by the riverside, which was sublet to him by the merchant Roy, who rented it from an Armenian, Gabriel Elijah. The Myowun pressed Elijah to evict Bayfield and threatened to confiscate the house if this were not done, but Bayfield firmly refused to go, saying that he had rented the house from Roy, not from Elijah and as Roy pointed out that he could not reasonably be called on to evict the representative of his own Government, the Myowun dropped the subject. But in other ways he continued to be aggressive and uncivil. He impeded the transit of stores and letters to Benson at the Capital and in October the Akunwun Antony Camaratta, at the Myowun’s instance, issued an order requiring all letters to be delivered to the Customs House. So when the vessel Mary arrived from Penang with packets for the Residency, the Akunwun refused to allow them to be delivered direct to Bayfield. Bayfield addressed an official order to the ship’s commander, Capt. Davis, who then handed the letters over to the Residency messenger, but the consequence of this was that the owner of the vessel, Cowasjee, was imprisoned. Bayfield drew attention to the injustice of such a proceeding but the Myowun received his messenger with violent language and declared that as Bayfield was not the Resident he had no right to address him in such a manner, though “if I had any debts to recover I might, he said, petition him as merchant.” The Myowun released Cowasjee but re-issued the order relating to letters and even threatened to punish Bayfield if he continued to receive packages in contravention to this command. This interference with the mails continued until Benson, at the Capital, protested to the Hlutdaw, but though the Myowun thereafter ceased to interfere with the postal arrangements, no apology for his behaviour was ever made. The incivility which Bayfield experienced was extended to other British subjects also. A warship H.M.S. Favourite, was in the port in October 1838 and three of the “young gentlemen” of the ship while riding through the town one day accidently knocked down a child, who received a slight bruise on the forehead but was otherwise uninjured, the three midshipmen were thereupon brought before the Yewun who sentenced them to a fine of Rs. 60, Bayfield, who had become accustomed to dealing himself with charges against British subjects, was indignant that no reference had been made to him and protested also against the infliction of such a penalty for a purely accidental injury. The fine had, however, been paid before he received news of the occurrence and it does not appear that the money was refunded. Part of the difficulty which the Residency experienced was due to the antagonism of certain of the British nationals in the port, one of whom, David Staig, did all in his power to prejudice the Burmese officials against the British representatives, being anxious to prevent the permanent establishment of a British consulate and the supervision to which his conduct would in consequence be subjected. Benson found conditions at the Capital intolerable and left Burma for good in April 1839, his assistant W.C. McLeod remaining in charge at Amarapura but McLeod also found it impossible to stay there and he removed to Rangoon in July. In the meantime the difficulties at Rangoon...... When McLeod reached Rangoon and took up his residence in the house formerly used by Burney, he managed, however, to keep on good terms with the local Government for some months. But relations between the Burmese Government and the Government if India were stained.... Thus Capt. Biden purchased the schooner Original from Crisp and laid her up for repairs, but when the repairs were completed the Akunwun demanded a fee of five rupees for every spring tide that the vessel lay on shore and refused to give port clearance for Moulmein until the appropriate amount of ten rupees had been paid, and further, Biden was compelled to pay a fee of six per cent on the purchase of the ship. |

|

... Messrs. Trill and Crisp’s brig Pyeen Boung, which had for eight years been assessed at ten rupees, were raised to over three hundred.

...The situation was not eased by the behaviour of the egregious May Flower Crisp, who was in the habit of telling the Burmans that the Indian Government was going shortly to invade and annex Burma, McLeod warned Crisp of the folly of indulging in such indiscreet talk, but without effect. ... McLeod found his position precarious, for the Residency was in the middle of town and he was exposed to the abuse of “the drunken followers of the officials and the insolent Burmese musketeers.” He resolved to withdraw to Moulmein and sent for a warship on which to take his departure, but when H.M.S. Conway arrived the Myowun dissuaded him from going and he finally removed to the house by the water which Bayfield had occupied. The position of foreigners in general was becoming more unpleasant.... Lt. Rodney and other offices of the Conway who had been ashore wished to leave the town at 8.30 one evening, were stopped by the gate keeper. R.S. Edwards, who was interpreter to the Residency, went to the Myowun and explained that the order that the gates should be closed at sunset had not been known to Rodney and his companions, but the Myowun was so abusive and threatening in his language that Edwards almost expected personal violence. Edwards at length managed to pacify the Myowun, who, however, while authorising the opening of the gates, ordered that gatekeeper to search the party, but Edwards dissuaded the guard from inflicting this humiliation on them. Shortly after the Myowun demanded that McLeod should vacate the house in which he was living. This demand determined McLeod to leave Burma for good..... On the 7th January 1840 he set sail and from this time onwards there was no further official communications between the Government of India and the Burmese Government until the year 1851. The British subjects of Rangoon did not follow McLeod’s example. They had property in the town and their means of livelihood lay there. But they no longer had the protection of the Residency and appeals to the Government of India had little effect... “a private trader who thus ventures into an unfriendly port for his profit does so at his own risk and cannot claim the interposition of his Government.” The Government of India, indeed, was not likely to have much sympathy with the troublesome type of trader who resided in Rangoon, especially as some of the British subjects there were more than suspected of habitually counterfeiting the old Madras rupee. ... When Col. Burney was at the Capital with no assistance in Rangoon, Mr Spiers acted as agent for official letter and stores, though in an honorary capacity, from 1833 onwards. But after two or three years some difficulty of an unofficial nature arose between Burney and Spires and the agency was given to Messrs. Trill and Crisp, who later arranged that a protégé of theirs J. Emmott, should be appointed Postmaster and Agent on a salary of Rs 70 per mensem. On Burney’s departure, however, as Bayfield remained in Rangoon in charge of the Residency, Emmott’s appointment lapsed and he went to Moulmein where he took employment in a shipyard. Again when it seemed probably that the Myowun would succeed in driving Bayfield away, he made a tentative arrangement for the revival of the Postmasters Office, proposing for the appointment a merchant named John Brown, whom he recommended because he seemed to get on well with the Burmese officials and “kept aloof from local squabbles.” This arrangement was not, however, brought into effect until Benson’s departure from Burma, when Bayfield also left. McLeod remaining for the time at the Capital, Brown was appointed Postmaster and became responsible for the forwarding of letters to the Residency. The jealousy which prevailed among the foreign merchants of Rangoon again showed itself in this connection, for May Flower Crisp and other merchants, though not Crisp’s partner Trill, petitioned the Government of India for the re-appointment of Emmott, but without success, for Col. Burney regarded him as unsuited for appointment since he had formerly been “Master Attendant at Tavoy or Mergui and lost the situation through intemperance, a habit of which I fear he has not entirely divested himself.” Emmott asserted that Brown had been selected because he was a personal friend of Bayfield, but this was denied by Benson. Brown continued to hold his office for the transmission of private foreign correspondence after the final withdrawal of the Residency and acted also as observer on behalf of the Government of India, sending reports about local conditions. His duties as Postmaster were carried out under sufferance of the Burmese authorities, who not unnaturally placed restrictions on his performance of them. At first the Akunwun expressed his intention to forbid Brown to receive the merchants letters and although this prohibition was not in fact enforced. Brown was forbidden to have communication with any ship after it had cleared the Customs House and since no ship could clear after 4 p.m. it was impossible to send out letters after that hour, nor was he allowed to retain packages in his office overnight. This circumstance led to a curious order from the Postmaster General in Calcutta, who, on receipt of a complaint from the troublesome Crisp, instructed Brown to keep his office open until a quarter to six, apparently under the misapprehension that “Mr Browne’s (sic) office is a regular post office in British territory.” Brown appears to have died in the late 40’s and the duties of postmaster were performed from March 1848 onwards by Hugh Brown, presumably some member of his family. Politically Rangoon had remained a backwater for some years following the war. When, however, the first shock of the disaster of 1826 had worn off, the Burmese Court began to ponder the possibility of regaining Burma irredenta and for such a purpose Rangoon must clearly be the centre of military operations. Further, although King Bagyidaw was himself reluctant to consider the prospect of war, the troubles which continually occurred on the Tenasserim frontier and which led to such episodes as the attack by a British force from Moulmein on the town of Martaban in 1829 as the only effective means of deterring the Martaban Myowun from encouraging dacoities on the Salween, seemed to suggest that war might occur at any time. Thus as early as 1832 there was much military activity in Rangoon. Burney, the Resident, wrote in that year, “I was struck upon my arrival here with the appearance of the town. The stockade had been rebuilt, the streets newly paved and improved and from a thousand five hundred to two thousand men may be seen under arms four times a month with scarlet jackets and good muskets escorting the Woongyee to the Great Pagoda. In no part of the Empire, not in the Capital itself, have I observed so much military preparation on the part of the Government and so much speculation as to the probability of peace or war with the British Government on the part of the local officials as in this town and I attribute this state of things as much to the constant disputes and jarring between Moulmein and Martaban as to the circumstance of our maintaining a steam vessel and a European regiment so immediately in this neighbourhood.” It is evident that for the moment Rangoon was again an important military centre. During Burney’s Residency, however, relations improved, but when King Tharrawaddy ascended the throne in 1837 the situation again became precarious. While Tharrawaddy did not want war, he nevertheless wanted to be free of the restriction which he felt the presence of a Resident at the Capital placed on his authority and the princes of the Royal house were enthusiastic for a war which should wipe out the disgrace of the previous defeat. These circumstances reacted on Rangoon. The disturbances accompanying Tharrawaddy’s usurpation of the throne had affected the town little, the Myowun made some attempt to put the stockade, which had entirely been again neglected, into a state of defence and he mounted a few guns at the gateways. But the defences were in such poor condition that it was impossible to hold the Fort and Tharrawaddy’s men marched in without encountering any resistance, the Myowun was put in irons and sent to the Capital. A rebellion which broke out in the province in January 1839, when a minlaung, who claimed to be the Sakya Min, the eldest son of the deposed King Bagyidaw, led an ineffective rising, was put down without difficulty and by the beginning of the following month all was quiet. |

|

... As early as December 1838 there was a concentration of troops in Rangoon and when a pilot, Anthony by name, casually pointed out to some officers of the warship Favourite the details of the navigable channel of the river, he was cast into prison and fined Rs 50 for the authorities were determined to prevent the communication to the foreigners of knowledge which would permit of unauthorised and unexpected entrance to the port.

Again in 1839 there was much talk in Rangoon of the possibility of an invasion by the British, not only Crisp but also a Muslim merchant, Mirza Mahomed Ali, informing the Myowun that the Government of India was about to take this step... McLeod noted that when the fortifications were ultimately completed they would constitute a formidable position.... In July 1839 a party of Frenchmen arrived and went to the Capital. They were private adventurers, but they were employed to build gun-boats for the King and there was talk that they would lay mines at the mouth of the river.... In this same year 1839, a merchant of Rangoon wrote, “My Burmah friends appear anxious to know the probable line of policy which our Government may take. The efforts now making to render the big Pagoda a Military Post is both expensive and troublesome to the inhabitants.” .... and still further changes were impending, for early in 1840 when an Indian merchant sought permission to erect a house within the Fort, he was informed “that the town was about to be removed towards the pagoda.” Again in October 1840 the Postmaster Brown wrote that “a report is current that it is the intention of His Majesty to visit this province about six months hence, preparatory to which one of the Woongyees is to be sent in the course of the next two months to superintend the erection of a Palace. The reasons assigned for His Majesty’s visit are said to be the fulfilment of a prophecy that a Palace will be built in the province of Henzawady in the Burmah year 1203 and to pay his respects to the Shooay Dagon Pagoda.” Again in this same month of October a party of Frenchmen arrived from Bourbon and it was thought that they had some secret business with the King. In November it was stated that “a stockade is now in progress of erection at a place cleared of jungle by the Woonduck when here, to serve, it is said, as a defence to the Palace that is to be built. Other reports state that the town is to be wholly removed to that place.” And in December Brown noted that “great activity had been shown in clearing away the jungle to afford space for the Palace and the forces that are to accompany His Majesty on his visit to this place will amount, it is said, to a hundred thousand men.” On the 8th February 1841 a disastrous fire occurred which destroyed many houses and a part of the stockade around the fort, but no attempt was made to restore the defences. “The portion of the stockade then burnt down remains in that state and I am not aware of orders regarding it having yet arrived.” Brown reported. “The impression that the town might be entirely removed by order from Court had hitherto deterred many from rebuilding their homes and intelligence has just been received that orders are on the way to the effect that the houses which were burnt are only to be repaired in a temporary manner in order that the loss to the owners may not be so great in the event of the removal of the town, of the propriety of which measure His Majesty will judge when he arrives here. The house for the reception of His Majesty is approaching completion, though after it is finished there will be much to be done in the shape of outer fences and offices, besides the houses that will be necessary for the accommodation of the Princes, all of whom it is reported will accompany His Majesty and other officers of Government, so that the whole cannot, I think, be finished before the commencement of the rains.” ... The King actually set out from Amarapura in September and he reached Rangoon on the 2nd October. He had with him, however, only about fifteen thousand men plus a further eight or ten thousand distributed in the province and it was soon apparent that war was not his intention. Tharrawaddy did indeed desire to restore the importance of Rangoon, possibly he did envisage making it someday a base for an attack on the lost territories and his sons publicly boasted that they were one day going to retrieve the disgrace of the last war. But for the time being the King’s policy was one of peace.... A new town in a stronger position, out of range from the river, guarded by fortifications not easily taken, was called for. Thus was built Tharrawaddy’s Rangoon, the plans for which had evidently been under consideration as early as 1839 when the fortification of the Pagoda was taken in hand. So the troops which the King had brought were utilised, not in fighting but in fortifying a new town and the King announced that when this work was completed he would return to Upper Burma. Nevertheless the period of his residence in Rangoon was one of political strain. The Commander of one of the Company’s ships, the armed Proserpine, which brought letters to Rangoon in November, was treated with discourtesy, he was kept in confinement in the Customs House and released only on the intervention of the merchant Capt. Spiers, while the interpreter whom he sent ashore with the letters was escorted to the Myowun’s house and not allowed to communicate with any of the inhabitants of the town. Also, in defiance of the treaties, a monopoly in timber was established, presumably to secure an adequate supply for the construction of the new town and the shipbuilding yards of Messrs. Crisp & Co. was sequestrated and used for the construction of ships for the King. ... Tharrawaddy’s object, however, was to a large extent already accomplished. A completely new city was established, standing well away from the river, with the Shwe Dagon Hill as its citadel. This new city, called Aung mye aung bnin, and also sometimes known as Ukkalapa after the traditional Kingdom of ancient days, covered approximately the area now known as the Cantonments. As with Alaungpaya’s Rangoon, few vestiges remain today and it is far from easy to trace the site. The town is described as having been “about a mile and a quarter from the river, it is nearly a square, with a bund or mud-wall about sixteen feet high and eight broad, a ditch runs along each side of the square and on the north side, where the Pagoda stands, it had been cleverly worked into the defences, to which it forms a sort of citadel. The distance from the Pagoda to the entrance of the town is about three-quarters of a mile and it is something more than that breadth from east to west. The old road from the river to the Pagoda, comes up to the south gate running through the new town.” The description of the town as a square is misleading, for at the north-east a salient of considerable size ran out at a point where there had formerly been an old fort which was now worked into the new system of defence. The Shwe Dagon formed the north-east corner of the town, the eastern face ran along the top of the ridge slightly eastwards of Signal Pagoda Road and the southern face ran parallel to and slightly south of Simpson’s Road, turned southwards to the east of and parallel to pagoda Road and then turned westwards again and ran, though not in an entirely straight line, south of the Jubilee Hall site, across the existing maidan, and beyond Godwin Road nearly to Budd Road, the western side ran eastwards of Budd Road up to the Military Police buildings at the south-west of the Prome Road Golf Course and the salient ran out across the Golf Course and beyond the Prome Road. The north face similarly cut across Prome Road and the Golf Course to the Pagoda and the remains of the bund on this side can be seen today, as also the remnants of the bund at the western extremity of the salient. The principal roads were a continuation of the old Great Pagoda Road running up to the Shwe Dagon to the east of modern China Street and then on the line of modern Pagoda Road. The great Lanmadaw, the new King’s Main Road which was now constructed on the line of modern Godwin Road, running from the new King’s Wharf which Tharrawaddy built by the waterside, up to the western entrance of the Pagoda and the old Wungyi’s Road, running to the Pagoda on the line of Signal Pagoda Road. There were other, internal roads, one of which approximated to Voyle Road and another to East Bazaar Road, but most of which do not appear to coincide with any of the roads today. The principal buildings were the Myenanaunggya – the Palace of Tharrawaddy Min, standing on a site on the modern maidan west of the Jubilee Hall, though this Palace was pulled down as soon as the King left Rangoon and the Myowun’s residence which stood south of the present Cantonment Church. There were numerous kyaungs and pagodas with the city, such as the Eindawya pagoda which still stands near Bishopscourt. Numerous barracks for troops stood within and close to the bund on the west and south sides. There were a number of tanks and swamps in the lower lying parts which have become the tanks in and to the south of the Cantonment Gardens. The water supply was, however, provided by thirty wells which the King cased to be dug. The town had thirteen gates, on the north or Myeni Gate, leading to Myenigon, on the east, the Leik khin Gate where the road now runs down from the Pagoda to the Royal Lakes, the Sin su Gate and the Kandagale Gate, on the south the Panbedan or Smith’s Gate, also known and the Kyagu Gate, the South Gate, the Nyaungbin or Banyan Tree Gate and the Thingyo or Thitnyo Gate, on the west, the Wetsu Gate, the Shin Sawbu Gate, the Matha gate and two other names are uncertain. Little information is available about Tharrawaddy’s town, however it was short-lived and during the brief period of ten years that it existed, was visited by few who cared to describe it. It was doubtless much like other Burmese towns of the day, with roughly paved streets, wooden or bamboo houses and few amenities. “Everything is commonplace,” it was said, “long, narrow streets, closely packed with houses on each side, no signs of municipal government, or of the sewers commissioners having visited the spot for many a long day.” The town was surrounded by an earthen bund with a timber stockade on top, but though the bund had been completed by the end of Tharrawaddy’s reign, the stockade had not and since no one was particularly concerned to finish the work, the new city remained for some years in a defenceless condition, with only the bund and the gateways to guard it. It was for this reason sometimes referred to as “the mud fort.” The Yondaw and the residences of the officials were removed to the new town and it was originally intended that the population of Rangoon as a whole should follow them. As early as December 1841 it was reported that “orders are out for all Burmese appertaining to the Militia, of which four houses support one musketeer, to remove into the new town of Ook-ala-bau,” and by the end of that month houses were already being pulled down and removed there. By March there were a few Burmese houses left in the old town and on the 27th of that month a fire which broke out in the Chinese quarter in Tatgale destroyed what were left. The only Burmans now remaining in the place where the Customs House staff and it was rumoured that they also were shortly to be removed These circumstances caused a good deal of alarm to the foreign mercantile community..... However, in the upshot old Rangoon was by no means abandoned completely. It continued to be a populous place, for the commerce and industry of the port were still situated there and all those connected with trade and the shipyards and that would be a considerable part of the population, seem gradually to have returned. Europeans, indeed, appear not only to have been allowed to retain their houses and godowns in the old town but also to have been definitely excluded from the new town unless they had business with the officials. Old Rangoon was “the only spot in which foreigners are allowed to reside,” and the approach of a foreigner to the new town was regarded with a jealous eye, an innocent attempt at making sketches of the place resulting in immediate arrest on the charge of espionage. The bund around the town, moreover, was more or less sacred, it is said, though probably it was military rather than religious considerations that led to the exclusion of foreigners from it. ....So Alaumngpaya’s Rangoon continued to be the business town... The Customs House Wharf, as it came to be known after Tharrawaddy built his new King’s Wharf at Lanmadaw, continued to be the meeting place of the mercantile community and was sometimes called the “Exchange” or “Gossip” Wharf. The old battery continued to stand, with the flagstaff nearby and not far away the “plain wooden spire of the Armenian Church” was still to be seen. The town was, however, sadly neglected in regard to public amenities. It was “more dismantled and desolate than ever”.... Navigation of the river also became more difficult, for, with that express design, Tharrawaddy had caused the grove of palm-trees, whose peculiar appearance gave the name to Elephant Point and which served as a landmark for sailors, to be cut down. Tharrawaddy’s visit to Rangoon had given a momentary impetus to trade, as he had very likely intended...... In October 1842 the Postmaster reported that as a result of the high price of timber produced by the monopoly “only one native vessel from the Madras coast had yet arrived at the port this season. The usual number of these vessels annually is fifteen.” Although in 1844 the monopoly was abandoned, other circumstances militated against a flourishing commerce...... “Several daring robberies have been committed here within the last few days and four people shot by the robbers when resisting them,” Brown reported. “The authorities appear to have taken little notice of their doings as they have taken no steps either to put a stop to them or for their apprehension.”.... Complaints of oppressive and arbitrary actions on the part of the local officials continued to reach the Government of India in this period. But in truth the foreign merchants in Rangoon were still as troublesome as ever and their conduct was such as to cause just irritation in the mind of not only the Burmese Government but also the Government of India. |

|

The irrepressible May Flower Crisp was as ever to the fore in causing trouble. In 1843 he wrote a letter to a Calcutta newspaper commenting on the political situation in Burma in such terms that, when the matter was brought to the King’s notice, he issued an order for him to appear before the Myowun to answer for his conduct. Crisp was at the time in Moulmein, but his son, Charles Malcolm Crisp, who was in charge of the firm’s business in Rangoon, was compelled to become surety for his father’s appearance within forty days on pain of being himself expelled from the King’s dominions. Crisp failed to satisfy the authorities and was formally expelled, though his son was apparently permitted to remain in Rangoon and to carry on business there.

In July 1847 Crisp returned to Rangoon in the hope of obtaining a reversal of the order of expulsion and while in the town he took it upon himself to approach the Myowun with a suggestion that the Residency should be re-established and finding the Myowun well disposed, he addressed the Government of India on the subject, optimistically suggesting that if “state economy or expediency interfere with the appointment of the Resident, in that event I submit that an honorary acting Resident might be appointed as the next step towards the gradual enforcement of our Treaties and which office I would respectfully solicit for my son Charles Malcolm Crisp, of course tendering my own services to Government should Government deem me better qualified to perform the functions of that important office.” Crisp was doomed to disappointment, however, for the Government of India merely directed him to “desist from taking any steps or adopting any kind of proceedings which would lead to the false impression that you are an accredited agent of the British Government,” while the Burmese Government refused to reverse its sentence of expulsion and by March 1848 he had had to return to Moulmein. He spent three days in jail during his stay in Rangoon “as he would not pay some money they demanded of him, but ultimately he was obliged to comply with all their demands. He was, however, back in Rangoon in 1851. Whatever the justification for the attitude of the local government towards the foreigners, it remains that trade declined rapidly during the 1840’s. In 1848 the Postmaster reported that “from the beginning of this year the imports of British goods from Calcutta are not one third of what they were in the same number of months of late years,” and in January 1849 he stated that “this is no longer a place for a merchant (that can leave it) to reside in because of the many arbitrary acts of Government. They seem to have thrown the Commercial Treaty aside altogether.” Again in February of that year he observed, “I cannot say whether it is by the orders of the Government or whether it is the local officers own doings that they oppress and harry us merchants in the way they do, but they do so and throw every obstacle they can in the way of our transacting our lawful business.” Brown frequently urged upon the Government of India the necessity of extending some degree of protection towards the British nationals living in Rangoon, for, in his view, if such protection were not given “the trade must in a great measure cease and were it to do so, I believe that it would be most sensibly felt in Calcutta and especially by those houses of business connected with Manchester and Glasgow.” The Myowun at the end of the 40’s by name Maung Ok, was even more arbitrary than his predecessors. According to rumour, he was habitually guilty of receiving bribes and “it was his constant practice to send his private friends, men who bore bad characters, about the town to excite quarrels among the rich and respectable and cause them to be brought up before him and accused in order that he might persecute them till they paid handsomely for their release. He had from twenty to thirty concubines. Whenever he took a fancy to a young maiden and her parents refused to give her to him, he would immediately accuse them upon some frivolous charge such as having glass windows to their house, the house being built like a Palace, or that they had a gold bedstead in it etc. and would confine them until they acceded to his wishes. He also, it was said, oppressed his people by excessive taxation and imposed unlawful exactions upon shipping. But whether this picture of the Myiowun’s character is a just one is open to doubt, for though he took extraordinary measures to obtain money, there is authority for believing that he wanted the money for the execution of pious deeds, since a visitor to Rangoon in 1852 recorded that he had visited “the new Pagoda, for building which the late Governor is said to have extorted money and so given rise to the war.” |

|

The Planning of the Modern City

The town of Rangoon, from which most of the inhabitants had fled, was quickly repopulated. By July there were said, with a good deal of exaggeration, to be sixty or seventy thousand inhabitants.... The civil population were not, however, welcome in what was left of “Tharrawaddy’s town, for that was the Cantonment area, while the old town, reported Godwin, “which stood on the river bank, has been utterly destroyed, it’s bricks now lying in heaps on its site.” Some measures had therefore to be taken for the housing of the population, which included hundreds of immigrants from India who had come in he train of the expeditionary force, besides many from Moulmein and plots of land were granted by the military commander for temporary occupation on the understanding that sites must late be vacated when some decision had been arrived at about the future of Rangoon. To place the matter beyond doubt a proclamation was issued by the General in the following terms: “It is to be distinctly understood that all persons now occupying houses and land in Rangoon, only occupy and hold the same on sufferance, present permission gives them no legal right to the property. The British Government is now at war with Ava and although the army has taken Rangoon, that circumstance gives the Commander no power to assign land or houses to any person whatever. All these matters will be arranged after peace has been restored either by British Commissioners or the Burmese Authorities, as the case may be.” The proclamation was the more necessary as there was yet no certainty of the future of Lower Burma. Certain measures were, however, necessary for the Government of the town, whether the occupation was to be permanent or not..... Steps were also taken to facilitate navigation by laying down buoys, employing a pilot-brig and constructing a new wharf; and to meet the expenditure so incurred a tonnage-duty of four annas a ton was imposed on all ships not in the employ of Government arriving in the port after the 22nd May: R.S. Edwards being appointed Collector for the purpose. For the time being, the town remained under military administration, Capt. Latter, and later Lt. R.D. Ardagh, acting as magistrates. .... A more serious affair was an attempted rising against the newly established British Authority which occurred twelve months later, when the company’s rule had been definitely established in Lower Burma. A plan was made to seize the Pagoda platform and to fire from it a gun as a signal to the town to rise, whereupon the plotters in the town were to seize the Treasury, fire the Court and the Customs House and kill all the English and their adherents. The plot was, however, discovered.... To prevent any further such attempts, the fortification of part of the Pagoda by means of an embrasured wall was decided upon and that part of the platform was set aside to be held by a guard as an arsenal and as a place of refuge in the event of disturbances. The Pagoda itself was “handed over under rules to the servants of the Pagoda who formerly were charged with it.” ... When the annexation for the Delta, now to be the commissioner’s division of Pegu, was determined on, provision needed to be made for the civil government. As early as the month of May 1852, only a few weeks after the occupation of Rangoon, certain of the European inhabitants who had now returned had petitioned Genl. Godwin for the appointment of a civil magistrate and had indicated as a suitable candidate for the post the turbulent May Flower Crisp, who had himself organised the petition. A copy of the petition was sent direct to the Governor-General, from whom it received short shrift, for the firm of Crisp & Co., which had so often been in hot water with the Burmese authorities, was equally in the bad books of Lord Dalhousie, since it had “sold powder, muskets and military stores” to the Burmese after it had become quite apparent that hostilities were about to occur. It is curious that Crisp’s son, C.M. Crisp, should also have provided information to the Governor General about the fortifications of Rangoon and should at the time of the attack on the Pagoda have shown the way to the eastern entrance by which the attackers took, with little loss, what would otherwise have been a very strong position, but the Myowun’s refusal to pay for the arms no doubt accounts for this. Lord Dalhousie rejected the petition and sent a plain warning that Crisp was to abstain from all interference with the people of the Pegu province on pain of deportation: from this it would appear that Crisp had already been trying to exercise some sort of authority in the town. Capt. Phayre, Commissioner of Arakan, appears to have been more favourably disposed towards the petition, however, writing to Crisp that he had “great claims from your long residence among (the inhabitants of Rangoon) and your intimate knowledge of their claims, interests and wants.” Annexation having been determined on, Lord Dalhousie drew up a scheme for the Civil Government of Pegu..... A Deputy Commissioner, in the person of Capt. T.P. Sparks, was also appointed for the Rangoon town and district... Capt. Phayre arrived in the Rangoon river on the 18th December and landed on the morning of the 19th. On the morning of the 1st the troops were paraded at 6 a.m. outside the stockade and the proclamation of annexation was read. In this way the civil government of Rangoon was inaugurated. ... The question also arose whether a lighthouse should be erected at the river mouth. Phayre proposed to station a lightship there..... The King’s ship which the Commodore had seized in January 1852 could be thus utilised..... A post-office system was inaugurated: the first Postmaster was C.M. Crisp, who received the appointment as a reward for his assistance at the storming of the Pagoda. The crimes of Messrs. Crisp & Co. were evidently soon forgiven. ... Compensation could therefore be paid only in respect of timber merchandise and personal property. No claims, moreover, could be admitted form other than British subjects, as such persons had no claim to protection, except in the case of the members of the American Baptist Mission “whose losses, in conformity to the Governor-General’s recommendation, founded on their sacred called and beneficent exertions, we are willing to make good, to the extent of such private property as consisted of necessity clothing and furniture.” The claims of Messrs. Crisp & Co. were rejected in view of the assistance which they gave to the Burmese and for some reason the claims of Moolah Cassim and Mollah Ibrahim were also rejected..... G.D. Wilkins, Bengal Civil Service was appointed commissioner for the investigation of claims.... The Prize Agents had been partially responsible for what was, in the eyes of men like Dalhousie and Phayre, an even graver impropriety. As in 1824, the troops had sought for loot and the Pagodas of Rangoon and of the other parts of the Delta had suffered. In the case of the more important pagodas it would seem that the Prize Agents were responsible, in other cases many of the military and naval officers were personally responsible. Phayre on his arrival in Rangoon found that once more even the Shwe Dagon had not been exempt from attack, the officer responsible for riving a gallery into the Pagoda, Major Fraser, R.E., advancing, however, the ingenious excuse that he wanted to see whether the pagoda could be used as a powder-magazine, though unkind critics opined that King Hsinbyshin’s treasure was more in his mind. Phayre addressed Brigadier Sir John Cheape, who was in command at Rangoon, pointing out the objectionable nature of such a proceeding which had, he was informed, caused great pain to King Mindon and might thus lead to a further breach of friendship. He also referred the matter to the Governor-General, drawing attention to “the disgraceful manner in which the Pagodas all over the province have been dug into and plundered” and observing that such acts must create ill-feeling among the local population as well as in Upper Burma..... ... “The Most Noble the Governor-General in Council has learnt with regret and dissatisfaction the continued destruction and injury to Pagodas and places of worship throughout the Province of Pegu. Such acts of violence in a time of war cannot be wholly prevented, but his Lordship in Council feels strongly the scandal which their continuance now is calculated to bring upon our national character and the exasperation which an open and almost universal desecration of their sacred places may produce in the minds of the people of Pegu. His Lordship in Council therefore desires to notify to all who are in the service of Government that whoever shall be proved to offend in this particular hereafter shall be punished with prompt severity. The Governor-General in Council expects that all officers within the Province, whether Civil or Military, will give special attention to the execution of the orders which are notified hereby.” But the chief problem confronting the new rulers of Rangoon was the planning of a city. As soon a it became apparent that the province of Pegu would not be retro-ceded, designs for rebuilding the capital were taken into consideration..... As Lord Dalhousie observed when he visited the town late in 1852, “the place will certainly grow in importance as a port if at all,” and there was from the first no question of siting the new town anywhere but on the river bank... ... Dr. William Montgomerie, who had come to Burma as Superintendent Surgeon with the troops in 1852. As a Surgeon on the Bengal Establishment, he had been posted to Singapore in 1819 and had remained there until 1842, he had thus been there when the new town of Singapore was established by Sir Stamford Raffles.... |

|

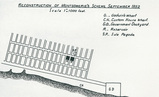

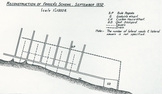

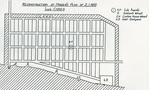

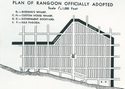

... Montgomerie’s suggestions thus provided for a town of chess-board pattern, equipped with a sanitary system and though the actual work of planning was not entrusted to him, the officer who undertook the task, Lt. A. Fraser, Bengal Engineers, did in fact largely follow the lines which Montgomerie had suggested. Shortly after Montgomerie submitted his memorandum, Fraser made a more detailed proposal. The major problem, in his view, as to deal with the flooding which was liable to occur at high-water. At every spring tide the greater part of the town was under water and the first consideration must be therefore to keep out the river water or at least to confine its ingress within useful limits. He proposed a bund along the riverside. A single line of piles, placed close together, should be carried for a distance of about 2,500 yards along the bank from Godwin's wharf down to the Government dock yard, the necessary timber could be obtained from the stockade at Tharrawaddy's town, which would supply all that was needed and more also....

... Having thus provided against flooding, Fraser would, following Montgomerie's plan, keep the Strand clear of buildings. The town behind the Strand should be divided into two parts,, an upper part and a lower part.... ... The swamp near the Sule Pagoda should be filled in with refuse of the upper town. The lower town should be divided by main sewers at right angles.... ... The scheme had to be modified to provide for a larger city and when Phayre came to Rangoon in the December, Fraser had already developed his first proposal into a more extensive plan. Phayre realised the essential importance of arriving at a proper lay-out and he informed Lord Dalhousie that "my first act after landing was to set about enquiries relative to the laying out of the town of Rangoon." He came to the conclusion that Fraser's plan as it had developed was sound. "It provides," he wrote, " for bunding out the river water, which now occasionally rises over the western part of the town at the King's wharf (now Godwin's wharf)... A road one hundred feet broad will also run from Godwin's wharf direct north to the Great Pagoda... ... The town as actually created extended only from Godwin's Road on the west to what is now Judah Ezekiel Street on the east and from the river on the south as far as the present Mongomerie Street and Commissioner Road on the north and allowed for an estimated population of only 36,000. Fraser's final plan, while taking Godwin's Road as its starting point, nevertheless adopted the Sule Pagoda as the centre of the town, so that the town was thus moved westwards as compared with Alaungpaya's Rangoon. A 200 foot road was formed running northwards from the river, with the Pagoda in its middle, in the western part of the town there was... The Cantonment area was excluded from the town plan. The military authorities were responsible for the planning of this region.... The new town plan having been accepted, it became necessary for the the roads and streets to be named..... |

|

... Closely bound up with the planning of the new city was the problem of land rights. Many of the former inhabitants and many new immigrants, Burmese and others, had taken advantage of General Godwin's proclamation allowing temporary occupation of land and hut and temporary buildings had been erected on the understanding that no claim was thus acquired to the land so used....

To emphasise the point Phayre, shortly after his arrival, issued the following order dated 24th December 1852. "Notice is hereby given that the whole of the land occupied by the town of Rangoon, together with the adjoining suburbs and vacant lands, as also both banks of the river extending from the mouth of the Panlan Creek to the mouth of the Pegu river is owned by the Government. No buildings now existing or which may hereafter be built without sanction from the authorities will be considered to entitle the occupants to property in the soil they cover. Arrangements are now making for an immediate survey of the town and adjoining country with the view of a regular plan of the town being laid out. When this is completed the manner in which it is proposed to dispose of building lots will be publicly notified. In the meantime all persons are hereby informed that no buildings should be erected without permission from the Magistrate and that due public notice will be given before building lots are disposed of." ... The decision, though necessary, not unnaturally caused consternation in some quarters and memorials were submitted by Europeans, Persians, Armenians and Indians demanding, in the case of the Europeans, the recognition of existing occupancy so far as was consistent with the plan of the new town and in the other cases the maintenance of former rights in the land. No memorials, stated Phayre, were received from any Burmese, who, it may be concluded, thought it useless to petition an alien government. All the claims advanced were, however, firmly rejected. |

|

... The only exception to the principle of sale by public auction would be made in the case of former inhabitants: thought no right of property could be recognised, at the same time some consideration was due to them; therefore those who were definitely known to have occupied certain sites before the war would be granted the sites now occupied by them or equivalent sites at the minimum selling-price, without their having to compete in an auction sale. Among those who so benefited was M.F. Crisp, who was allowed to purchase in this manner a site for a ship-building yard.....

Similarly the proposals for taxation were modified. Phayre had suggested a municipal tax which should produce Rs. 50,000 a year and a land tax.... The Rules also provided that ground should be reserved for markets and a space by the river set aside as a fish market. For the sake of hygiene "no buffaloes, oxen, cows or pigs will be allowed to be kept in any lot within the town, nor will any slaughter-house or manufactory which is offensive or injurious to public health be allowed to be established, not will the burning or burying of the dead be permitted within the town." Later a restriction on the keeping of gunpowder was added, the amount to be kept in any one place not to exceed twelve pounds. It was also provided that the land and municipal taxes should be collected as from the 1st May 1853 even from temporary occupants who had not acquired land by purchase from the authorities, the urgent need for money for such purposes as police and the circumstance that taxes were already being collected in other parts of the Pegu Division justified this step.... The allotment of town sites appears to have proceeded rapidly, by the end of 1853 most of the sites in the blocks between the Strand and Merchant Street had been disposed of.... |

|